It’s official: my next book, In the Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor, is in its final stages of production. Thanks to the efforts of the brilliant and generous folks at Wolke Verlag in Berlin, it will include an index; photos from Val Wilmer, Dagmar Gebers, and others; and a foreword by German jazz journalist Markus Müller (author of FMP: The Living Music, also published by Wolke).

I had originally planned for the image above, a painting by Martel Chapman, to be the cover. I commissioned it from him because I loved the work he’d done on Victor Gould’s albums Clockwork and Thoughts Become Things, and Nduduzo Makhathini’s In the Spirit of Ntu. But the Wolke folks said no, that they couldn’t make it work from a design perspective. They sent me a cover mockup using the painting, and they were right; it didn’t look nearly as good as some of the other ideas they offered, using more traditional — but still quite vivid — photos of Taylor. So we agreed on one of the other options, and as soon as the typography and color scheme are finalized, I’ll show it to you.

At this point, we’re hoping to send it to the printer by the end of May, and have it done by sometime in June. (They turn things around fast on their end; I have no idea how, but I definitely appreciate it.) How long it will take to reach distributors and bookstores after that, I have no idea, but as of now, I’m guessing at a late summer/early fall street date.

So right now I’m starting to drum up publicity for it, since I don’t have the budget to hire someone. If you’re a journalist reading this, and you have any interest in possibly reviewing In the Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor for a newspaper, magazine, website, your own newsletter, or anyplace else, hit me up and I’ll send you a PDF. I am also very available for interviews about the book, or anything else.

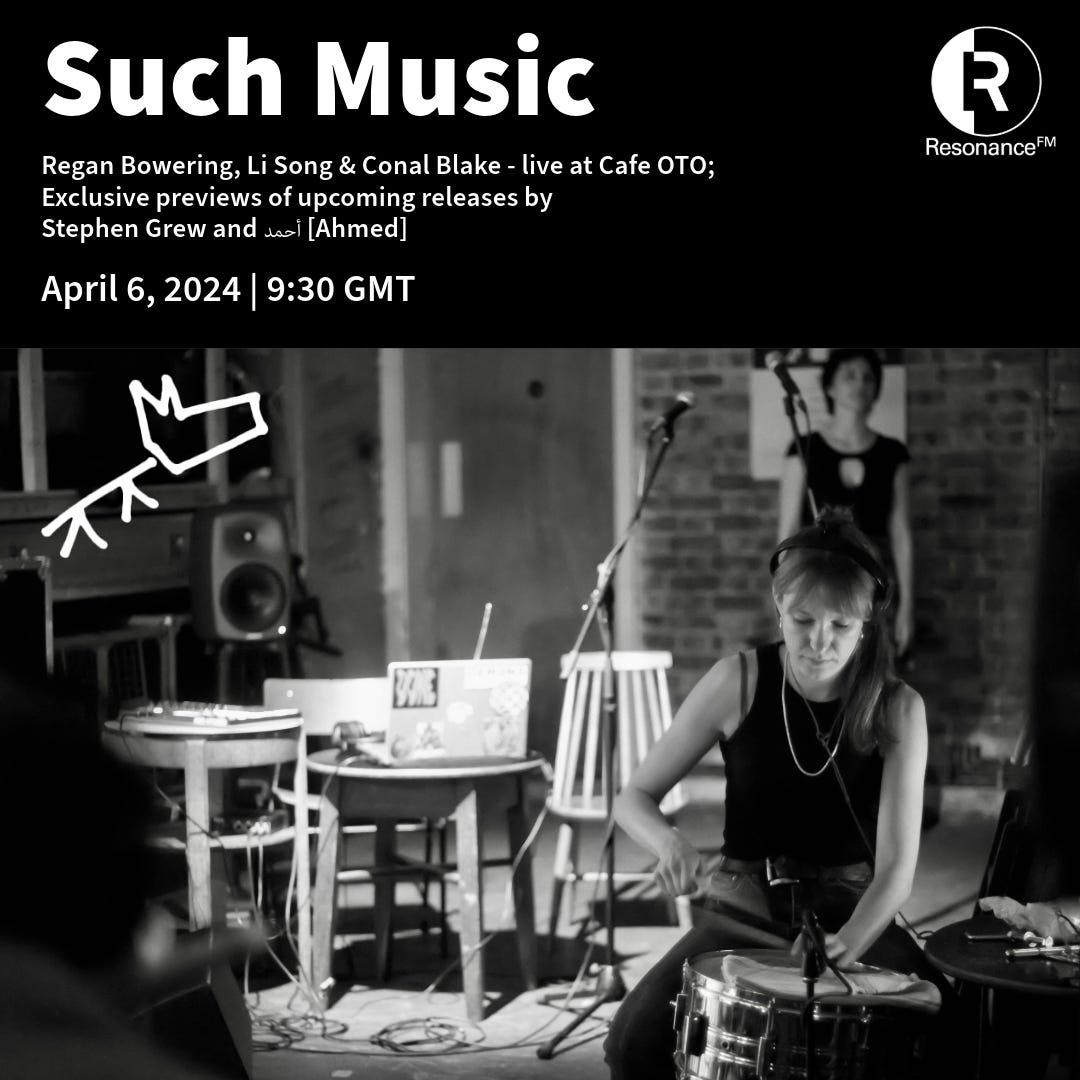

Hosted by Rihards Endriksons, journalist and artistic director of Latvia’s Skaņu Mežs festival, the monthly radio show Such Music (listen on Mixcloud) is devoted to new works of free improvised music, either previously unheard or created specifically for the show. As of March 2023, the show is produced in collaboration with Burning Ambulance. This month’s episode includes an unpublished live recording of the percussion-electronics trio of Regan Bowering, Li Song and Conal Blake playing at Cafe OTO in London, as well as exclusive previews of upcoming releases by Stephen Grew and أحمد [Ahmed]. Click here to listen.

Alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley was the kind of musician who never stopped surprising audiences — in the best possible way. Born in Florida in 1928, he and his cornet-playing brother Nat were musical partners from childhood. They moved to New York together in 1955, and Cannonball made several albums for Savoy and EmArcy before joining Miles Davis’s sextet in 1957. He can be heard on Milestones, Kind of Blue, and Porgy and Bess, and Davis played on Adderley’s 1958 album Somethin’ Else, his sole release on Blue Note.

In 1959, the Davis band minus Davis (Adderley and John Coltrane on saxophones, Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, Jimmy Cobb on drums) recorded Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago — a studio session, though its title might suggest otherwise. That same year, he formed a band with Nat, pianist Bobby Timmons, bassist Sam Jones, and drummer Louis Hayes and recorded The Cannonball Adderley Quintet in San Francisco, which was live, and which was a crucial step in the evolution of what would become known as “soul jazz,” a style which would make the Adderley brothers stars.

Cannonball Adderley was a brilliant player who could get as virtuosic as you liked, but always kept (at least) one foot in the blues. He was also a charismatic bandleader and raconteur, delivering witty monologues from the stage that served to provide context for the music and big up the members of his band. Nat Adderley, meanwhile, was a prolific composer — his “Work Song” is a jazz standard — and maintained a solo career, leading his own groups and recording as a sideman with Sonny Rollins, Milt Jackson, Jimmy Heath, Johnny Griffin, Oliver Nelson and others.

Once the Cannonball Adderley Quintet was established as a live draw, it would have been easy for them to record one assembly-line hard bop record after the next, but they were surprisingly adventurous in the studio. On 1961’s Plus, they brought in Wynton Kelly and had their then-regular pianist, Victor Feldman, move to vibes; African Waltz expanded the group into a big band; they made bossa nova records and an entire album of tunes from Fiddler on the Roof; and on 1968’s Accent on Africa, added percussion, a Varitone electronic attachment to Adderley’s sax, and even vocalists.

The bulk of their catalog, though, was recorded live, documenting not only their catchy, hard-swinging soul jazz repertoire but Adderley’s winning personality and way with a crowd. Albums like Cannonball in Europe, Nippon Soul (recorded when the band was a sextet, with Yusef Lateef on reeds; Charles Lloyd was also a member for a while), and Country Preacher: “Live” at Operation Breadbasket (hosted by Jesse Jackson) are all superb. One of Adderley’s most famous albums, Mercy, Mercy, Mercy!: Live at “The Club”, actually wasn’t live; like Pharoah Sanders’ Live at the East, Tom Waits’ Nighthawks at the Diner or Slayer’s Live Undead, it was recorded in a studio, with an invited audience.

Adderley featured a parade of highly regarded pianists in his band, including Junior Mance, Bobby Timmons, Barry Harris, Victor Feldman, and George Duke, but the one who stuck around the longest — almost a decade — was Joe Zawinul. He joined in 1961, and didn’t leave until 1970, when he’d already worked with Miles Davis on In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew and was about to form Weather Report with saxophonist Wayne Shorter. Zawinul wrote several of the Adderley group’s most popular pieces, including “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” “Walk Tall,” and “The Scavenger,” in the process moving the band from soul jazz to jazz-rock fusion and even toward free/out playing. Of course, none of that exploration would have happened without the boss’s approval, and Cannonball Adderley — like his own former boss, Miles Davis — was in the habit of choosing bandmates who would push the music forward, while still giving the people what they wanted.

Two previously unreleased live recordings by two different Cannonball Adderley bands are out this week from the Elemental Music label. The first, Burnin’ in Bordeaux: Live in France 1969, features Zawinul on keyboards, Victor Gaskin on bass, and Roy McCurdy on drums. The second, Poppin’ in Paris: Live at L’Olympia 1972, has the Adderley brothers and McCurdy joined by keyboardist George Duke and bassist Walter Booker. The recordings were made by and for French radio, and were dug out of the ORTF archives by producer Zev Feldman and remastered. They both sound fantastic.

Burnin’ in Bordeaux is a two-disc set running a little over 90 minutes. It begins with a 10-minute version of “The Scavenger,” on which McCurdy lays down a driving but subtle beat as the band goes out, but not too far out, in a way that reminds me of the 1965-68 Miles Davis quintet. At the end of the tune, they take a few minutes to fix the sound, so we get to hear Zawinul and Gaskin playing solo in turn as technical conversations go on in the background. The next piece is a romantic Brazilian number, “Manhã de Carnaval,” followed by a high-energy version of “Work Song.” Each of these pieces is about 10 minutes long, but after that, the performances get more concise, with most tunes brought in for a landing after five to eight minutes. Adderley’s wit and charm are on display at several points, most notably when he introduces a version of “Somewhere,” from the musical West Side Story, by describing composer Leonard Bernstein as “a musician in New York who leads a big band…called the Philharmonic Symphony of New York.” Zawinul switches to electric piano on a version of “Why am I Treated So Bad” by the Staple Singers, and when his solo erupts at around the 3:30 mark, with McCurdy’s snare cracking behind him, it’s like if Ray Charles had joined Iron Butterfly. What makes Burnin’ in Bordeaux great is its breadth. From challenging hard bop to foot-stomping soul jazz grooves to the neoclassical intricacy of “Experiment in E” to romantic ballads, Adderley and his band could and did play just about anything they felt like, and through a mix of virtuosity and charisma, they kept the audience on board through all of it.

After Zawinul’s departure, Adderley brought in keyboardist George Duke, who had already recorded with violinist Jean-Luc Ponty and spent two years as a member of Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention. After leaving Adderley’s band, he would return to Zappa’s. (I wrote about Duke’s 1970s career here.) In the summer of 1971, Adderley’s quintet, with Duke on keyboards and Walter Booker on bass, spent a week at the L.A. club the Troubadour, where they recorded a double live album, The Black Messiah. A bonus LP of leftovers, Music, You All, was released in 1976. During their Troubadour stint, the quintet was joined by a number of guests, including saxophonist Ernie Watts, clarinet player Alvin Batiste, guitarist/singer Mike Deasy, and percussionists Airto Moreira and Buck Clarke. As a result, The Black Messiah in particular is one of Adderley’s most stylistically wide-ranging records: there are electric blues-rock tunes, abstract fusion jams, soulful groove pieces, and everything in between.

A little over a year later, on October 25, 1972, the Cannonball Adderley Quintet appeared at the Olympia Theatre as part of the Paris Jazz Festival. No special guests this time, just a hard-working road band utterly in sync and speaking as one. The set, which lasts just under 80 minutes and thus fits on a single CD, includes a 20-minute version of Duke’s piece “The Black Messiah,” a 19-minute version of Zawinul’s “Dr. Honoris Causa” (a dedication to Herbie Hancock that Weather Report would make their own), and a long deconstruction of the standard “Autumn Leaves,” which Adderley had first made his own on Somethin’ Else. The set rocks along, never flagging or getting too abstract, and ends with what feels like a medley of three Joe Zawinul compositions: “Directions” (a fanfare-like tune that Miles Davis opened almost every set with between 1969 and 1971), “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” and “The Scene.”

Cannonball Adderley died on August 8, 1975, having suffered a stroke a few weeks earlier. He released more than 50 albums, studio and live, in his lifetime, and had been working to the end; he recorded his last two studio albums, Phenix and Lovers, that year.

Adderley was a virtuoso musician, creative enough to work in almost any context, but had a populist instinct that rarely steered him wrong. For 20 years he was able to change with the times while remaining essentially himself, and his musical and personal bond with his brother gave his bands an instantly recognizable sonic signature, whatever other factors might be at play. His discography is large and broad enough that getting the full measure of the man would require years of focused listening. But these two new live albums paint a vivid portrait of what he was up to night after night on the road, and are pure pleasure.

That’s it for now. See you next week!

I'm very interested in your book. I made the film "All the Notes' ...maybe Ii could help ..I'd love to read more .....best.....chris felver

Why not include the amazing painting of Cecil that you commissioned inside of the book?