Before we begin: S. Victor Aaron has written a thoughtful, in-depth review of Ivo Perelman’s The Foreign Legion (with Matthew Shipp and Gerald Cleaver). It’s one of 40 Perelman albums now available via the Leo Records Bandcamp page.

In 2019, the art historian Carel Blotkamp published The End: Artists’ Late And Last Works, a book that analyzes the work of multiple painters — though Raphael and Piet Mondrian are the only two to get whole chapters to themselves — and discusses which ones developed a new, creative “late style” (he cites Claude Monet, Pierre Bonnard, Max Beckmann, Alberto Giacometti, Lucian Freud, Louise Bourgeois) and which didn’t, instead burning out or becoming clichés (Georges Braque, Marc Chagall, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst).

In the introduction, Blotkamp writes, “There is nothing ambiguous about the end of an artist’s creative activity, and we could, conceivably, treat his last work just like any other work. Yet, somehow, things are different. Whether we are amateurs or professionals, we feel compelled to assign the bookend of an artistic career a special meaning… It is almost inevitable that the last work should take on mythical proportions.”

A hundred years earlier, the German art historian A.E. Brinckmann used the term Altersstil (“old-age style”) to describe the late paintings of the Old Masters. In a New Yorker review of the Blotkamp book, Max Norman described this as “the probing, introverted counterpart to the dynamism and extroversion of youth.”

Some take the opposite perspective; writing about Beethoven, Theodor Adorno declared, “The maturity of the late works does not resemble the kind one finds in fruit. They are for the most part not round, but furrowed, even ravaged. Devoid of sweetness, bitter and spiny, they do not surrender themselves to mere delectation.” He believed that the prospect of death inspired artists to greater heights of subjectivity — they had nothing to lose and were working for themselves, not the listener or reader or viewer.

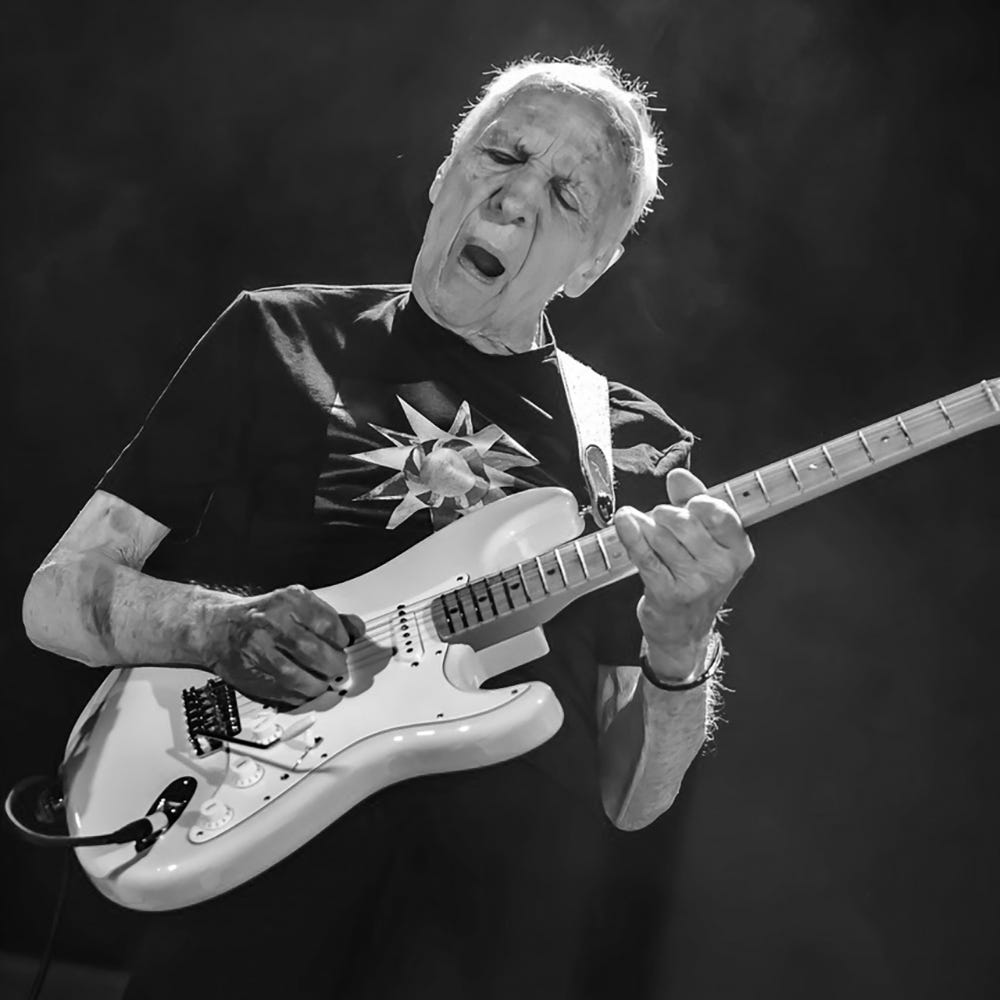

In my experience, artists’ late work often possesses an inner calm, a relaxed mastery that manifests in clarity of expression. Sentences become shorter. Brush strokes become more clearly visible. Shots draw less attention to themselves. Music shifts toward traditional forms. Communication with the reader/viewer/listener becomes more direct. There’s less ego on display, and less trickery. Over the last 15 years or so, Robin Trower, who turned 80 last month, has become a uniquely focused artist and a master craftsman in exactly this manner.

Trower first came to prominence as a member of psychedelic prog-rock act Procol Harum. (He doesn’t play on their best-known song, “A Whiter Shade of Pale.”) After five albums, he left the group, making his solo debut with 1973’s Twice Removed From Yesterday, joined by bassist/vocalist James Dewar and drummer Reg Isidore. That trio stayed together for 1974’s Bridge Of Sighs, Trower’s best-selling album, but on the following year’s For Earth Below, Isidore was replaced by Bill Lordan, who would stay for five more studio albums and a live album, ending with 1981’s B.L.T. (which featured Jack Bruce on bass and vocals).

In Rock and the Pop Narcotic, Joe Carducci described Trower’s music as “austere refinement of the blues… simple midtempo (or slower) melodic ideas sketched minimally by the rhythm section usually creating a blue mood or one of foreboding from which Trower solos with an ecstatic lyricism and a working sense of the electric guitar’s idiomatic potential. His colors don’t vary much but he is their master.”

In the Seventies, Trower was in competition with hard rock acts, and his music could be as cranked-up as theirs; the first song on Bridge of Sighs, “Day of the Eagle”, is audibly indebted to the work Jimi Hendrix was doing in the last year of his life, though Trower also cites B.B. King and Albert King as major influences on his style. But even that song, which begins with a howling guitar riff and almost punk drumming, downshifts in its second half, and Trower embarks on a lengthy and quite beautiful overdubbed dual-solo passage, throwing ideas back and forth with himself. (The 2024 deluxe box set version of the album is worth investigation, as it includes an alternate mix of the album with some striking differences.)

Trower recorded less frequently in the ’80s, ’90s and 2000s than he had in the ’70s, but he never disappeared completely. And recently, he’s been almost as prolific as he was in his heyday, releasing 10 albums since 2010, the latest of which, Come And Find Me, is out next week.

Blotkamp writes, “While it has never been easy for any artist to maintain peak levels of achievement over a lifetime, the pace of change in art has accelerated to such a degree in modern times that it has become very difficult for older artists to remain relevant.” Robin Trower has not been “relevant” in the narrow, commercial sense by which rock music is judged for 40 years, but his work has never been more heartfelt and direct than in the last 15 years, and if that kind of thing speaks to you, his recent catalog is a tastefully laid-out display case full of gems.

Like his classic-era albums, these late works feature a relatively small group of backing musicians. The core group consists of Trower on guitar, bass, and sometimes vocals, with Livingstone Brown on keyboards, occasional bass, and production, and Chris Taggart on drums. Beginning with 2021’s United State Of Mind (an unusually elaborate record — horns! strings! — which was collectively credited to Trower, reggae vocalist Maxi Priest, and Brown), he’s mostly stepped back from the microphone. Richard Watts, a slightly hoarse and restrained singer somewhere between Paul Rodgers and Keith Richards, appears on 2022’s No More Worlds To Conquer and Come And Find Me. Joyful Sky, from 2023, was a collaboration with Sari Schorr (she got a “featuring” credit on the cover), whose own albums offer the kind of blues-rock that soundtracks bar scenes in streaming shows you’ve never watched.

What makes Trower’s work of the last 15 years distinctive is an autumnal, even mournful quality that was not present 50 years ago, when he launched his solo career. This is to be expected, perhaps, in the work of a man recording blues-rock albums in his 60s and 70s, but the degree to which he has seemed to be gazing into the darkness is striking. Album titles like Something’s About To Change, Coming Closer To The Day, and No More Worlds To Conquer carry a different weight than they might coming from someone younger. Trower is a widower now, and has suffered health problems in recent years that have forced him to cancel shows and sometimes entire tours.

In a 2018 interview with Guitar World, Trower insisted Coming Closer To The Day wasn’t meant to be morbid or navel-gazing. Though he admitted, “You spend a fair amount of time thinking about your past… Let’s face it — I have a lot more years behind me than in front of me,” he said, “I’m not thinking about dying — far from it. What I’m saying is, ‘If I’m nearer the end than the beginning, then I’ve got to get going.’ So many people my age back off the pedal and coast, but I’ve got no time for that. I have to work harder than ever. In terms of writing and playing the guitar, I want to do my best work, and the time for that is now.”

(It’s worth noting that Trower’s recent album covers, beginning with 2016’s Where Are You Going To, feature his own paintings. The images are colorful collections of geometric shapes arranged in simple patterns, painted with thick, heavy brush strokes.)

Setting aside Joyful Sky and United State Of Mind, which are differentiated by their vocalists and some adjustments in style, all of these Trower albums sound quite similar. Taggart’s drumming is steady and minimalist; he plays fewer fills than AC/DC’s Phil Rudd. Trower lays down simple bass lines that lack the suppleness of James Dewar’s work on his ’70s albums, but they get the job done. The songs follow traditional forms — electric blues, occasionally R&B. The big rock riffs of his ’70s output have been replaced by slowly sung vocal melodies, augmented and commented on by short flourishes of guitar.

Trower’s voice is thin, but it’s got grit. He reminds me of ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons. But occasionally, as on 2017’s Time And Emotion, he’s shadowed by female backup singers who play a similar role to those on late-period Leonard Cohen albums: supportive, but also just a little bit sardonic. And while he’s no poet, his lyrics can get pleasingly dark at times; the first song on 2016’s Where You Are Going To is called “When Will The Next Blow Fall?”, and it’s a tale of existential terror not far from Bone Machine-era Tom Waits, or Warren Zevon in jeremiad mode.

Come And Find Me is Trower’s latest album. Its songs slot neatly alongside the others, with no stylistic left turns or experiments. He’s not trying to find new listeners; he is who he is, and he does what he does. It opens with “A Little Bit of Freedom”, which shows the potential to scale the ecstatic heights of “Day of the Eagle”, but Trower only permits himself a few flourishes when soloing. The next song, “One Go Round”, simmers, and he plays more (duration) and less (notes) at the same time.

Lyrically, the album seems unexpectedly earthbound and more focused on the present than his recent work. He’s not staring into the abyss or contemplating the void, as he seemed to be on earlier albums. The songs are either about love (“Tangled Love”, “I Would Lose My Mind”) or vaguely about freedom and (non-political) independence (“The Future Starts Right Here”, “A Little Bit of Freedom”). But as always, the primary draw is Trower’s guitar playing, which remains a stately, graceful version of post-psychedelic blues, with occasional bursts of Seventies hard rock fervor. Come And Find Me isn’t a spiny, bitter album; nor is it probing or introverted. In a way, it feels like Robin Trower has achieved psychic equilibrium and is expressing himself with a simple clarity that at its best has a stunning impact.

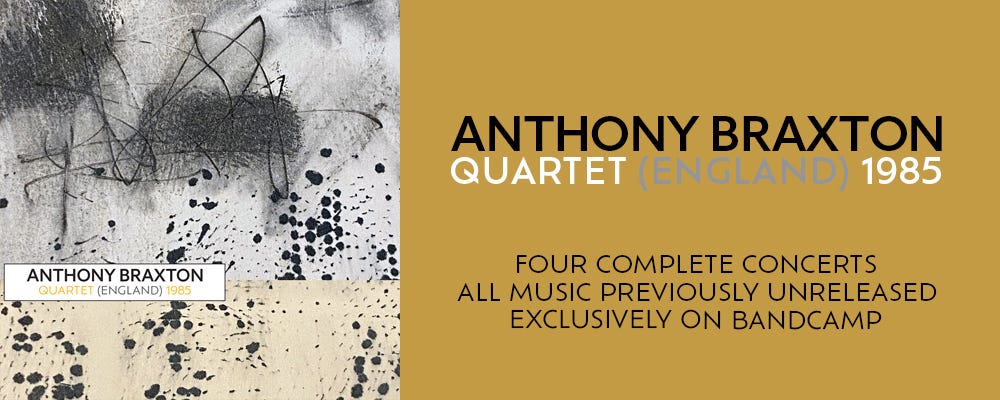

That’s it for now. See you on Friday, when we’ll be talking about the music of newly minted NEA Jazz Master Marilyn Crispell.

Trower is so underrated! He didn't even make Rolling Stone's list of best rock guitarists. But he's far more influential than many who did. Fun fact: he gave lessons to a young fellow named Robert Fripp.

Very underrated indeed. And when you're first and foremost a jazz fan, people will perhaps understand that you also like Santana or Zappa, but Robin Trower? Robin who? It was a relief when long time ago I read on his website that Nels Cline is a Trower fan... That said, I still prefer his earlier work. Robin Trower live, In city dreams, Caravan to midnight and Victims of the fury being my favorites. Cheerio!