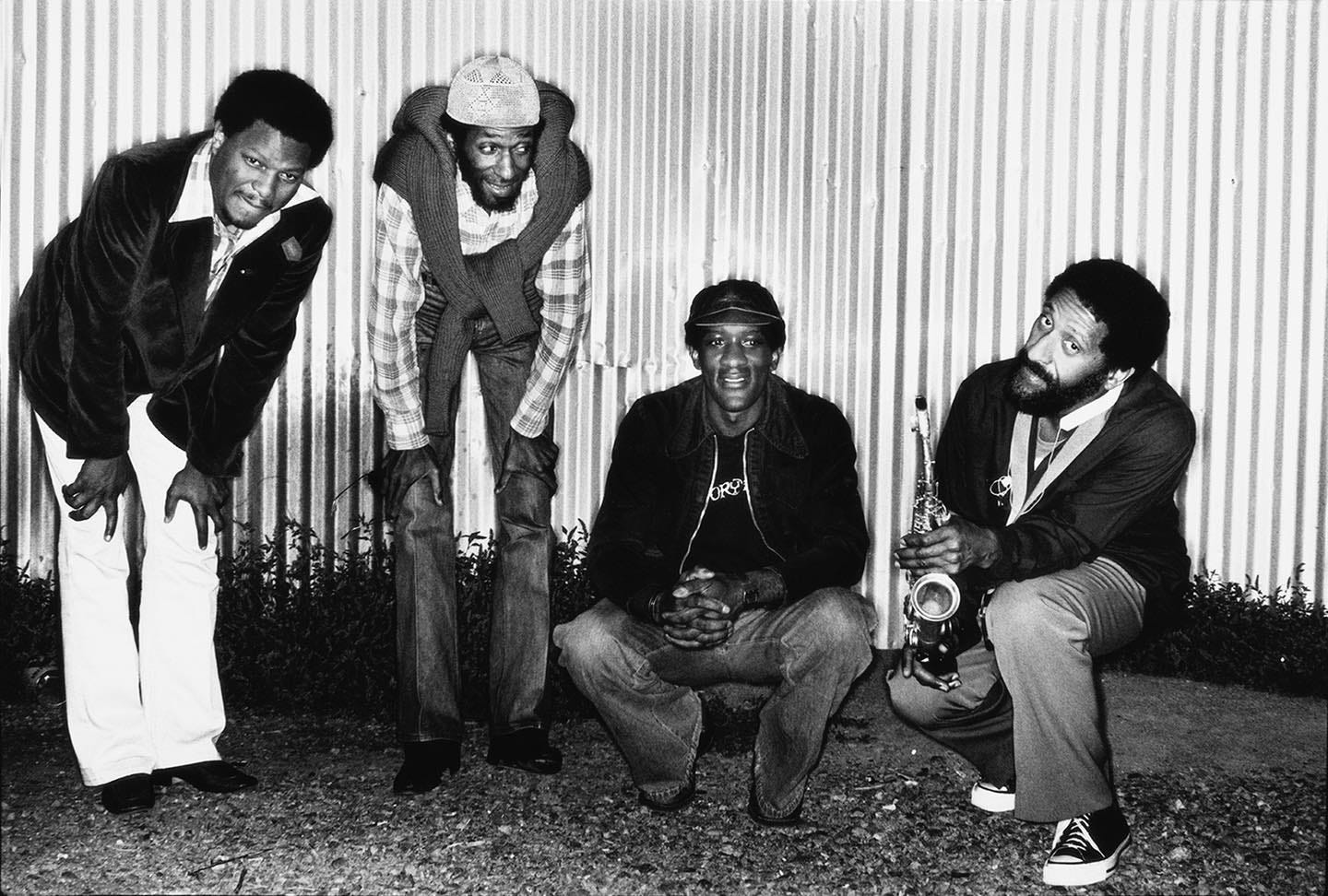

It occurred to me that I haven’t been writing about jazz here all that often. Since August, I’ve only written five newsletters on jazz-related subjects, so it’s time to refocus my attention in that direction for a little while. And since pianist McCoy Tyner has an amazing posthumous album out on Friday — Forces of Nature: Live at Slugs’, with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson, bassist Henry Grimes, and drummer Jack DeJohnette — I’ve decided to share with you an expanded version of a piece I published on the main BA website back in 2018: a guide to all the albums he released between 1970 and 1979. There are 19 of them with him as leader, and one by the Milestone Jazzstars, a supergroup featuring Sonny Rollins, Ron Carter, and Al Foster. Get comfortable.

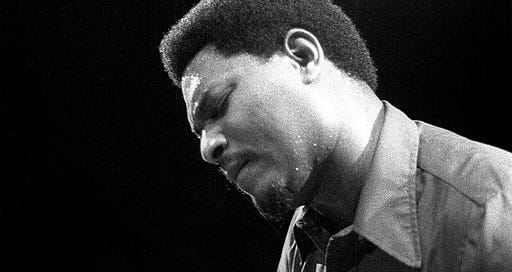

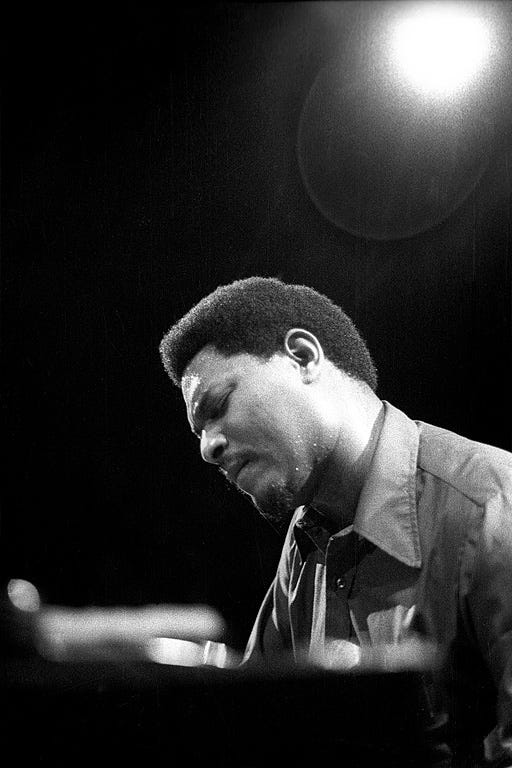

Pianist McCoy Tyner is one of the most important musicians in modern jazz. He first popped up on some folks’ radar as a member of the Jazztet, a group co-led by flugelhornist Art Farmer and saxophonist Benny Golson, but his career was made in 1960, when he joined John Coltrane’s group. (They knew each other before that; Coltrane recorded Tyner’s composition “The Believer” in 1958.) Though he recorded a few times under his own name, and did some sideman work here and there, he mostly stayed with Coltrane until 1965, making a string of legendary albums. He finally left when the saxophonist’s music had become so free and so aggressive that Tyner claimed he could no longer hear himself. That can seem hard to believe when listening to his playing, because he can be as torrential and overwhelming as Coltrane was — but, at the same time, he’s capable of extraordinary tenderness and beauty.

The 1970s were inarguably Tyner’s peak as a creative artist under his own banner. Between 1970 and 1979, he recorded 19 albums, only one of which was held back for later release. Most of these were on Milestone, a label that doesn’t get the recognition it deserves these days. They had an incredible roster during that period that included Tyner, Joe Henderson, and Sonny Rollins, among others, and kept the flag flying for high-powered, quality acoustic jazz even during the heyday of fusion. They ought to be every bit as revered as Blue Note, Impulse!, or CTI, but they’re not.

Tyner’s first recording session of the 1970s was on February 9, 1970; it was tracked for Blue Note, where his tenure was coming to an end, and held in their vaults for three years — an astonishing decision, considering the personnel and the quality of the music. Extensions features Gary Bartz on alto saxophone, Wayne Shorter on tenor and soprano saxophones, Alice Coltrane on harp, Ron Carter on bass and Elvin Jones on drums. It contains just four longish tracks, two of which are in the 12- to 13-minute range and two are between seven and eight minutes long. The opener, “Message from the Nile”, features a mantra-like horn riff played to sound as much like as Middle Eastern/North African reeds as possible; Bartz’s saxophone sound will loosen your fillings, and Shorter’s soprano is as whiny as it’s ever been. Still, the extremely subtle reverb put in place by producer Duke Pearson and engineer Rudy Van Gelder keep it from becoming too maddening. Carter mostly bounces in place, and Jones stays steady rather than exploding; the real joy, other than Tyner’s high-powered piano soloing, is Coltrane’s harp, which surges forth in the piece’s latter moments, launching the music into a whole other world. She’s absent on “The Wanderer”, which is a more conventional post-bop sprint that builds up to a rattling Jones solo. On “Survival Blues”, which opens with a minute of solo piano, Coltrane is a subtle background presence, and Shorter takes an extremely tough tenor solo; it’s Carter’s minimal, rubber-bandlike solo, though, that’s the real surprise. It’s more like a bass break than a bass solo, since he barely shifts from the primary line he’s been playing, and Jones is heard softly keeping time behind him, waiting for his own turn in the spotlight, which when it comes is explosive. The album ends with the pastoral “His Blessings.” Tyner and Coltrane shimmer past each other in rippling waves of notes as the horns softly murmur and twitter like birds. Jones thunders across his toms from time to time. The last sound we hear is a bowed drone from Carter.

Asante, recorded on September 10, 1970, was similarly held back by Blue Note, and not released until 1974. As its title and cover (featuring a man dancing, surrounded by a circle of onlookers) indicate, it’s heavily influenced by African music. The band includes Andrew White on alto sax, Ted Dunbar on guitar, Buster Williams on bass, Billy Hart on drums, and Mtume on percussion, and Songai Sandra Smith contributes vocals to the first two of its four tracks. In addition to piano, Tyner plays wood flute here and there. The first and last pieces, “Malika” and “Fulfillment”, are 14 minutes long each; the other two, “Asante” and “Goin’ Home”, are just over six and just under eight, respectively. The first two tracks are a swirling blend of modal jazz, post-A Love Supreme spiritual keening, and Smith’s passionate vocals. “Goin’ Home”, though, starts the second side off with some gritty funk that happens to feature extra percussion (and, at one point, Tyner softly strumming the piano’s strings behind Williams’ bass solo). White’s saxophone and Dunbar’s guitar team up for a melody line straight off a Grover Washington, Jr. date for Kudu, as Williams and Hart roll on, loose but tight. “Fulfillment” is an extended burner with high-speed soloing from White that alternates between manic repetition of short cell-like phrases and extended squawking blowouts, atop a rhythmic bed that skitters and surges. Tyner himself frequently lurks in the background, and when he does come forward, his playing is jagged and harsh. Unlike Extensions, it’s not that hard to understand why Asante was initially shelved; there are some great moments, but the two long pieces are too long and diffuse, and only “Goin’ Home” really makes an impact.

After leaving Blue Note, Tyner signed with Milestone. He’d record for them until 1981, recording 19 albums in 11 years (and three more in the ’90s). His debut for the label was Sahara, recorded in January 1972. It’s an ambitious and exploratory album —in addition to piano, Tyner plays koto on “Valley of Life” and flute and percussion on the 23-minute title piece. He’s joined by Sonny Fortune on alto and soprano saxophones and flute, Calvin Hill on bass, and Alphonse Mouzon on drums. Hill and Mouzon also play reeds and percussion on “Valley of Life” and “Sahara”, and Mouzon also plays trumpet on the latter piece. “A Prayer for My Family” is a solo piece on which Tyner can be heard softly singing along with the piano; his playing is remarkably unfettered and powerful, while also displaying extraordinary technique and control; at times, it predates Cecil Taylor albums like Indent, Silent Tongues and Air Above Mountains. “Valley of Life” is a fascinating piece of world music-ish introspection, with Tyner strumming the koto as his bandmates tootle and softly play percussion around him. The two traditional jazz pieces, “Ebony Queen” and “Rebirth”, are high-energy blowouts, the former melodic and the latter free and hard-charging. Fortune’s alto solo on “Rebirth” reaches Pharoah Sanders-esque heights. The album-side-long title track begins with some Art Ensemble of Chicago-style trumpet and “little instruments,” before Tyner embarks on a sprinting piano workout, his left hand striking the keys so hard it’s surprising they don’t clatter to the floor. Later, as Fortune uncoils a marathon, almost circular-breathing soprano solo, Tyner can be heard on flute and percussion behind him, before sitting back down at the keyboard to slam home heavy chords that keep the reedman from spiraling all the way out into space. The flutes, percussion, and Mouzon’s elephant cries on the trumpet all return during Hill’s bass solo. Sahara is one of Tyner’s best-selling and most critically acclaimed albums, and there’s good reason for that.

Song for My Lady was recorded at two sessions, on September 6 and November 27, 1972, and released in February 1973. Like its predecessor, it features Sonny Fortune, Calvin Hill, and Alphonse Mouzon; on the first and last track, they’re joined by Charles Tolliver on flugelhorn, Michael White on violin, and Mtume on percussion. The opening “Native Song” runs 13 minutes, and the closing “Essence” is 11:20; in between those two epics, we get a version of the standard “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”, the title track, and a solo piece, “A Silent Tear”. Song for My Lady is a less unfettered album than Sahara; Tyner and the band have found their footing and are now exploring the territory they’ve staked out for themselves. But the actual performances are fantastic. Tyner’s playing is thunderous, though the piano isn’t recorded with anything like the kind of volume or impact it would have live. He sounds okay on “A Silent Tear”, but at too many other times he’s clangy and honky-tonkish, which when coupled with Hill’s rubber-band ’70s bass and Mouzon’s wood-block drum sound is…unfortunate. White’s violin is also quite shrill; while his own Impulse! albums from the ’70s had a nice, lush, Alice Coltrane/Pharoah Sanders feel, here he sounds like Ornette Coleman, scraping away at the strings. The horns are the only instruments really well served here; Fortune is authoritative and declamatory, even on flute, and Tolliver’s flugelhorn is rich and full. Anyway, the music is great, easily overcoming sonic deficiencies with speed and power; “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”, which Tyner had recorded a dozen years earlier with John Coltrane (that version is on Coltrane’s Sound), is breathtakingly fast and relentless.

Echoes of a Friend is a solo disc, recorded in Japan on November 11, 1972. It includes two new original compositions, “The Discovery” and “Folks”, but they make up the second side. The first three pieces are all either written by John Coltrane or strongly associated with him — “Naima”, “Promise”, and the standard “My Favorite Things”, which the saxophonist, accompanied by Tyner, memorably stripped down to a vamp he could ride into eternity. With no other instruments to mix, producer Tetsuya Shimoda and engineer Tamaki Bekku can really let the piano swell and blossom, and it does; the relatively tinny, barrelhouse sound of Song for My Lady, also recorded in autumn 1972, is gone here, replaced with an instrument in full roar. The three Coltrane-associated tunes are delivered in a thunderous onslaught, with only a few brief seconds of silence to let the listener catch their breath, and the album’s second half commences with the nearly 18-minute “The Discovery”. Without saying so, it’s divided into two movements. The first begins and ends with gong strikes, while the second starts with gentle vibraphone and ends with a massive chord that rings out for nearly 10 full seconds. The final piece, “Folks”, shimmers and ripples, with tons of powerful low-end rumbles from Tyner’s left hand. At times the music on Echoes of a Friend sounds like contemporaneous solo work by Keith Jarrett, but for the most part it’s uniquely Tyner, and it’s a phenomenally energetic performance. He was on a creative hot streak in the early ’70s, and this album is close to essential.

Song of the New World, recorded in April 1973 and released in July of that year, is a slight step down, but still very good. It features a 10-piece big band horn section on three tracks and a 10-piece string section (plus an oboe) on two others, in addition to the core band of flautist Hubert Laws, saxophonist Sonny Fortune, bassist Juini Booth, and drummer Alphonse Mouzon. It opens with a sprint through Mongo Santamaria‘s “Afro Blue” that’s much more widescreen than the version Tyner recorded with Coltrane on 1963’s Live at Birdland. The addition of congas to the ensemble gives Mouzon someone to bounce ideas off, and rocket fuel for his own drumming; the beat is simultaneously skittering and relentless. The second piece, “Little Brother”, is more groove-oriented, a swinging hard bop workout that barely employs the additional horns, mostly leaving them quiet so Tyner can dive-bomb all over the keyboard. Virgil Jones takes a ripping trumpet solo, though. The string arrangements on “The Divine Love” and “Song of the New World” are reminiscent of those on Alice Coltrane albums like World Galaxy and Universal Consciousness; they surge and trill behind Tyner’s hard-driving piano. “Some Day” is a placid ballad mostly notable for Booth’s bass solo, which is excellent. All this music is of extremely high quality, as was to be expected, but the big band and semi-orchestral arrangements don’t really add that much to the tunes, which could just as easily have been performed by Tyner’s road band.

On Enlightenment, recorded in July 1973 and released later that year, we get to hear that live band — with Booth on bass and Mouzon on drums, and Azar Lawrence replacing Sonny Fortune in the saxophone slot — in full cry, at the Montreux Jazz Festival. (Miles Davis’s septet also played the festival that year, and I think he was listening, because eight months later, when he recorded Dark Magus at Carnegie Hall in March 1974, Lawrence was invited onstage for a live audition, as was guitarist Dominique Gaumont. The latter man passed the test, and is also heard on Get Up With It; Lawrence never played with Davis again.) The 70-minute performance, released as a double LP, is divided into roughly three sections. It opens with the three-part “Enlightenment Suite,” two 10-minute spiritual-jazz workouts with a four-minute solo piano passage in the middle. At a few points, Lawrence plays through some kind of electronic device that turns his horn into a wavering, bumblebee-like synth. Two medium-length pieces, “Presence” and “Nebula”, make up the second section of the set. Each showcases Tyner’s increasingly powerful, surprisingly free playing. The final third of the show is a single epic piece, the 24-minute “Walk Spirit, Talk Spirit”, a churning gospel-funk number on which Mouzon drives the band hard, as everyone — Tyner included — digs deep into the blues. Note that this is a performance of entirely new music; none of these tunes show up on any other Tyner album of the era. This was the man and his band at their absolute peak, bringing it live with blistering intensity. When “Walk Spirit, Talk Spirit” ends, the audience positively erupts.

Here’s video of the Montreux performance, in two parts:

Just two days before his onstage audition for Miles Davis, Azar Lawrence was in the studio with Tyner. The pianist’s next album, Sama Layuca, was recorded March 26-28, 1974; the Dark Magus concert took place on March 30. Sama Layuca features a nine-piece band that includes John Stubblefield on flute and oboe; Gary Bartz on alto sax; Lawrence on tenor and soprano; Bobby Hutcherson on vibes and marimba; Buster Williams on bass; Billy Hart on drums; and Guilherme Franco and Mtume (also a member of the Davis band) on percussion. Several of the compositions, notably the title track and “La Cubaña”, are built on Latin rhythms, but Tyner’s fondness for modal jazz structures remains intact, too. One thing sets Sama Layuca apart from other Tyner albums of this era: no solo track. One of the short pieces — the 3:02 “Above the Rainbow” or the 4:57 “Desert Cry” — would typically be an unaccompanied showcase for the leader, but in the former case, he’s joined by Hutcherson for a gentle, atmospheric duet, and the latter piece is a Middle Eastern-tinged ballad with shimmering chimes, high-pitched reeds, and softly throbbing bass. The album ends with its longest piece, the 16:27 “Paradox”, which rises from a soft piano-vibes-and-percussion intro to a charging post-bop marathon, with Hutcherson adding ringing overtones, and a positively maniacal solo starting at the 8:45 mark. Gary Bartz’s saxophone sounds heavily reverbed, like he’s playing from the farthest corner of the room, but his solo has a gospelish fervor which Williams and Hart encourage, slowing the beat down to a clap-and-sway groove. There’s a lot going on on Sama Layuca, and the louder you play it, the more you hear.

On August 31 and September 1, 1974, Tyner and his road band — saxophonist Azar Lawrence, bassist Juini Booth, drummer Wilby Fletcher, and percussionist Guilherme Franco — played at San Francisco’s Keystone Korner. The gigs were recorded, and the highlights were released on the pianist’s second double live album in as many years, Atlantis. Like 1974’s Enlightenment, it can be a lot to take in; the bandmembers are soloing ferociously, particularly Lawrence, who’s deep into a post-Coltrane calling-the-spirits zone. Fletcher is a hard-hitting, almost rock-like drummer, and Franco matches his energy level, throwing a constant clatter at him like he’s marching in a Carnival parade in Brazil. Booth’s extended solo on the 18-minute, album-opening title track is positively booming, and Tyner, of course, is tearing up the keyboard as always, spinning out long, elaborate lines while maintaining a serious hard bop groove at the same time. In addition to four Tyner originals — I love the fact that he was using live gigs to premiere new material — Atlantis features versions of Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood” and the standard “My One and Only Love”. The former is a wild, rippling solo performance that heads into Cecil Taylor territory, almost sounding like Tyner’s got four hands at times.

Tyner’s next album, 1975’s Trident, was his first trio set since 1964’s McCoy Tyner Plays Ellington, and that album featured two Latin percussionists, Willie Rodriguez and Johnny Pacheco, on four of its seven tracks. Trident is all trio, and features the return of the rhythm section from 1967’s The Real McCoy and 1970’s Extensions, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Elvin Jones. But Tyner can’t help throwing some weirdness into the mix: in addition to piano, he plays harpsichord and celeste. Only half the pieces are new; the group also tackles Antônio Carlos Jobim’s “Once I Loved”, John Coltrane’s “Impressions”, and Thelonious Monk’s “Ruby My Dear”. The moments when Tyner plays harpsichord are fantastic, particularly on the album’s first track, “Celestial Chant”, because he doesn’t try for a baroque classical feel. Instead, he sounds like a ’60s garage psych rocker. He pulls a similar trick with the celeste to kick off “Once I Loved”, before allowing the bouncing bossa nova groove to draw him back to the piano. Hearing Tyner play a Monk composition is inherently fascinating, because I can think of few pianists with less in common. Monk’s deliberately clunky, off-time approach to the keyboard is almost the opposite of Tyner’s linear, high-energy, even frilly style. But Tyner clearly loves Monk’s music, otherwise he wouldn’t have recorded the piece, and it does wind up bringing something out of him. It’s well worth hearing, as is Trident as a whole.

In January 1976, Tyner made Fly with the Wind. The primary band included Hubert Laws on flute and alto flute, Ron Carter on bass again, and Billy Cobham on drums, but that core ensemble was augmented by 10 string players, a piccolo player, an oboe player, and a harpist. This could have been a pleasantly drifting dinner music album, except for one factor: Cobham. The Panamanian-American drummer, well known for his work with the Mahavishnu Orchestra, on the Carlos Santana/John McLaughlin album Love Devotion Surrender (and its subsequent tour), and as a solo bandleader, is an absolute monster behind the kit, blending military precision with blinding speed and a positively assaultive sense of swing. His barrages — there’s no better word — of percussion drive Tyner to ecstatic heights, especially since there’s no saxophonist to fight him for time in the spotlight. The title track is eight and a half minutes long, and ends with a fade; this is music that feels like it’ll sweep over you like a tsunami and just never stop. The strings are as big a part of that as Cobham’s relentlessness; when they come in, they surge like something off a Barry White 12”, adding a lush shimmer to already over-the-top tunes.

Seven months later, in August 1976, Tyner was back in the studio with an entirely different band to make Focal Point. This time, he was joined by three saxophonists: Gary Bartz on alto and soprano (and clarinet), Ron Bridgewater on tenor and soprano, and Joe Ford on alto and soprano (and flute). The rhythm section was Charles Fambrough on bass and Eric Gravatt on drums, with Guilherme Franco on percussion. Gravatt is an under-recognized drummer; he was in Weather Report early on, and played on Eddie Henderson’s Inside Out, Joe Henderson’s Canyon Lady, and Julian Priester’s Love, Love, before leaving the music industry to become, of all things, a prison guard. But his work here is terrific, especially the way he makes the toms sound like plastic buckets. No, seriously, that’s a good thing in context. On the aptly titled “Mode for Dulcimer”, Tyner plays the dulcimer, getting a hillbilly twang out of it that’s fantastic. When it becomes a conventional piano-horns-and-rhythm piece like so many others he’s recorded, though… Still, Gravatt’s bucket drums and Franco’s tablas keep things exciting.

Over the course of four days in April 1977, Tyner recorded a double album, Supertrios, with two different rhythm sections. On April 9 and 10, he worked with bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams; on April 11 and 12, Eddie Gómez and Jack DeJohnette took their spots. Tyner wrote five of the 12 compositions, though two of them — “Blues on the Corner” and “Four by Five” — were re-recordings of pieces from 1967’s The Real McCoy. The others were standards like Duke Ellington’s “Prelude to a Kiss”, John Coltrane’s “Moment’s Notice”, Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life”, “Stella by Starlight”, and Thelonious Monk’s “I Mean You.” It’s interesting to compare what Carter and Williams did here — aggressive, driving swing, with the drummer in assault-and-battery mode — with what they did two months later, backing Herbie Hancock at the sessions for Third Plane, also released on Milestone, and Herbie Hancock Trio, released by CBS/Sony, but only in Japan. Carter’s bass is almost offensively rubber-bandish on the Hancock album, and Williams’ playing displays a lighter touch, though he still can’t resist the occasional machine-gun snare fill. Similarly, Gómez and DeJohnette had worked together in Bill Evans‘ trio for a time in 1968, and they, too, tiptoed around more behind Evans. Tyner wanted a high-impact rhythm section, and he got one. The reworking of “Four by Five” is a perfect example. On the original recording, he was backed by Ron Carter and Elvin Jones, but the bouncing melody was carried by Joe Henderson’s tenor saxophone, and when the piece kicked off, Jones was doing a light dance on the cymbals, only rarely driving the beat home. On this new version, Tyner plays the opening fanfare faster, and slams his way across the keyboard, while DeJohnette is barely touching the cymbals at all, instead opting for high-speed kick-and-snare breakbeats with just a dash of hi-hat for punctuation.

Recorded over the course of a week (with three days off in the middle for Labor Day weekend) in September 1977, Inner Voices is a slightly weird album. Two of its five tracks feature a 12-piece horn section (four trumpets, four trombones, two alto saxes, one tenor sax and one baritone sax), while another offers just trumpet, trombone, alto, tenor, and flute; there are two different drummers (Eric Gravatt on two tracks, Jack DeJohnette on two others); and on four pieces, a seven-member vocal group sings wordlessly. The opening track has neither horns nor drums—it’s just Tyner, bassist Ron Carter, and the singers “la-la”-ing along. That’s all they do on the entire album, is pop up here and there “la-la”-ing through a melody a time or two. But other than that, the music is extremely high-energy — like, Buddy Rich level — modal hard bop with big blasts of horn every once in a while. It’ll get your heart pumping for sure. Inner Voices is probably the least essential of this whole run of albums, because the vocalists are a failed experiment and the rest of the music isn’t distinct enough to overcome that factor. But it’s still far from disposable.

The Greeting is the first of three live albums Tyner recorded in 1978 (one of them, Counterpoints, wasn’t released until 2004, but we’ll be dealing with it anyhow). It was taped at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco on March 17 and 18, and the band includes Joe Ford on alto saxophone and flute; George Adams on tenor and soprano saxophones and flute; Charles Fambrough on bass; Woody “Sonship” Theus on drums; and Guilherme Franco on percussion. This was the first of Tyner’s 1970s live albums not to feature all new material. He revisited “Fly With the Wind”, from the album of the same name; “The Greeting”, from Supertrios; and John Coltrane’s “Naima”. There were two new compositions, though: the opening “Hand in Hand”, and “Pictures”. The former is a gospel-ish fanfare with minimal soloing from Tyner or anyone else, that adds flute, chanting, and Brazilian percussion to move it away from the Keith Jarrett-on-Impulse! territory it would otherwise inhabit. That’s followed by a nearly 15-minute take on “Fly with the Wind” that’s the album’s longest piece by far. The combination of drums and additional percussion give it a strong rhythmic drive, and George Adams delivers a fierce solo. Tyner himself goes quite far out at times, approaching the hyperspeed romanticism of Cecil Taylor during an unaccompanied passage. “Pictures”, the second new composition, is quite obviously a Tyner piece—it has the modal groove and powerful melody that most of his compositions offer, and the band runs it like an NFL play, Theus and Adams in particular: the saxophonist takes a wild, roaring, Pharoah Sanders-esque solo, and the drummer is in demolition mode. Despite the lack of new material, The Greeting captures a really good band absolutely steamrolling through a very strong set of music.

Passion Dance is another live album, recorded in Japan with Ron Carter and Tony Williams. This time, there are no new compositions at all. They perform two John Coltrane pieces — “Moment’s Notice” and “The Promise” — as well as “Passion Dance” and “Search for Peace” from The Real McCoy, and the title track from Song of the New World. Williams is in ultra-precise machine-gun mode; his solo on “Moment’s Notice” sounds more like Billy Cobham. What sets this album apart, though, and makes it worth hearing, is that the bassist and drummer are only present on that track and “Song of the New World”. The three pieces that make up the bulk of the album feature Tyner alone, taking his music apart and putting it back together. The nearly 12-minute version of “Passion Dance” is pretty intense, while “Search for Peace” begins as a tender ballad but eventually becomes a florid explosion of color, and while “The Promise” is more subdued, the way Tyner hammers the keyboard’s lower end is remarkably punishing at times. This isn’t an essential album, but it’s a reminder that he was always trying to do something new, even in a context — a club date in Japan — that could have allowed him to coast.

Counterpoints: Live in Tokyo was recorded in 1978, but not released until 2004. It features more material from the same performance that was documented on Passion Dance, with Ron Carter on bass and Tony Williams on drums. Again, the full trio doesn’t perform throughout; Carter and Williams are only heard on the opening “The Greeting,” where the bassist takes a pleasingly bouncy solo, and the final two numbers, a version of Duke Ellington’s “Prelude to a Kiss” and a new piece, “Iki Masho (Let’s Go)”. The other two tracks, “Aisha” and “Sama Layuca”, are solo piano pieces. The former is a shimmering ballad that rises to one thundering crescendo after another, only to recede again; the latter is pure pounding force throughout, as though he’s trying to compensate for the absence of the heavy Latin percussion from the studio version by slamming the keys. It’s mildly interesting that even though Counterpoints came out in 2004, it’s only 48 minutes long, like a vinyl LP would be. It raises the question of why Passion Dance wasn’t a double album, since the material here is of the same quality as on the earlier release.

Together was recorded August 31 and September 1, 1978 and released the following year. It features an octet: Freddie Hubbard on trumpet and flugelhorn; Hubert Laws on flute and alto flute; Bennie Maupin on tenor saxophone and bass clarinet; Bobby Hutcherson on vibes and marimba; Stanley Clarke on bass; Jack DeJohnette on drums; and Bill Summers on conga and percussion. The opening “Nubia” adapts Tyner’s frilly modal jam-out style to a heavy blues structure, with occasional big blaring fanfares from the horns. It’s practically headbang-worthy, especially with Clarke’s massive bass sound, which occupies more of the midrange than the low end of the mix. Hubbard’s trumpet solo is explosive, full of upper-register trills and screams. “Bayou Fever” opens with a powerful shuffling beat from DeJohnette, accented by low moans from Maupin’s bass clarinet. When the other horns come in, it becomes a wild, dark journey into the swamp, like an unexpectedly weird interlude on a Dr. John or Leon Russell album. And when it becomes (briefly) a duo between Maupin and a bow-wielding Clarke, it gets even weirder, and that’s before Hutcherson’s vibes come dancing in like skeletons from an old black-and-white cartoon. “One of a Kind” is rip-roaring hard bop with another roof-scraping Hubbard solo; “Ballad for Aisha” is so much more structured than “Aisha”, from Counterpoints, that it’s practically unrecognizable, but of course since this album was released 25 years before that one, this lush studio take was the definitive version. Together is a widescreen, in-your-face album. Everyone is playing hard, and it’s produced with a loud, brash 1970s sound. Even the flute manages to blare, somehow. But it’s more than just a tidal wave of sound; there’s real sensitivity and empathetic interplay here. Even this late in the decade, Tyner was far from running out of creative steam.

In September and October 1978, Tyner went on tour as part of the Milestone Jazzstars, a group put together by label head Orrin Keepnews that also featured Sonny Rollins on tenor sax, Ron Carter on bass, and Al Foster on drums. They released a double live LP, Milestone Jazzstars In Concert, which has only ever been available in the US on an edited CD (a version of “Willow Weep for Me”, played solo by Carter, is cut) and isn’t on streaming services. In the late ’90s, though, a Japanese 2CD edition came out with all the material from the original double LP and five bonus tracks; that’s the version I have. It’s an interesting document of what has come to be known as “stadium jazz” — see also the work of V.S.O.P., discussed here — but it’s more than that. In addition to the quartet pieces, Rollins, Carter and Tyner all get solo numbers, Tyner and Carter duet on “Alone Together”, and Rollins and Tyner team up for “In a Sentimental Mood”, and the original release ends with a trio version of “Don’t Stop the Carnival”, without the pianist. If you can find a copy, it’s well worth hearing.

Horizon was recorded April 24 and 25, 1979, and released in 1980. It featured Joe Ford on alto and soprano saxophones and flute; George Adams on tenor sax and flute; John Blake on violin; Charles Fambrough on bass; Al Foster on drums; and Guilherme Franco on percussion, bringing Tyner’s most productive and creative decade to a close with a wild and surprising left turn. The thing that separates Horizon from every other McCoy Tyner album, obviously, is the presence of John Blake’s violin, but until you listen to the album, you really don’t know just how dominant he is. He takes lengthy solos throughout the disc, and they’re ferocious, swooping-and-diving things in the realm of Jean-Luc Ponty or the Mahavishnu Orchestra. On the 12-minute opening title track, he basically takes over completely; the main melody is arranged for piano and violin, and he gets a long solo spot, bolstered by an avalanche of rhythm from Foster and Franco. Fambrough kicks off “Motherland” with a massive bass sound almost like a guembri; Adams steps into the spotlight with a bicep-flexing, vein-popping tenor saxophone solo, but it’s difficult not to stay focused on the throbbing bass. “One for Honor” is a fast trio piece; Tyner tears up the keys, and Fambrough gets a short but potent solo. The album closes with “Just Feelin’”, a muscular soul jazz tune. Horizon isn’t just a great album on its own terms; it’s also a great capper to an amazingly creative decade’s worth of work.

There’s one more album to deal with, which I’m adding here at the end as a kind of bonus track. In 1976, Blue Note released Cosmos, a double LP containing tunes from two different recording sessions, one from April 4, 1969 and one from July 21, 1970. We’ll skip over that first session, and deal with the second one here. It features Gary Bartz on alto and soprano saxophones, Hubert Laws on flute and alto flute, Andrew White on oboe, Herbie Lewis on bass and Freddie Waits on drums. Only three tunes were recorded, but they were relatively long. “Forbidden Land” runs 13:57, “Asian Lullaby” was 7:27, and “Hope” was 14:17. All the music on Cosmos was experimental, and somewhat hard to classify, so it’s understandable that Blue Note kept it in the vault. The 1969 session featured a string quartet, and as mentioned, this one features oboe. “Forbidden Land” begins with some exotic trills and frills, not that far away from what he was doing on Extensions (recorded five months earlier, and also featuring Bartz), and the oboe, as played here, has a piercing tone that’s almost Middle Eastern, which works really well set atop the typical-for-Tyner modal rhythm. Waits pounds the toms a lot, giving the music a kind of rumbling, tumbling forward momentum. “Asian Lullaby” gives Bartz a hypnotic, mantra-like melody line, but the drums are a little too busy (even before the drum solo), the flute is a little too frantic in the background, and Tyner is playing with way too much power for it to actually serve as any kind of lullaby. “Asian Reverie” might have worked as a title. “Hope” feels, for its first few minutes, like Tyner is returning to the mode of John Coltrane’s Meditations; it builds up slowly, the reeds crying like mourners. But then the rhythm section starts to jog along, and he settles in for a long piano journey that takes the piece past its halfway mark. The second half of the piece features solos from Bartz and Lewis. All three tracks are good-not-great, and there’s not really a full album’s worth of music here (three tracks, 35 minutes), but it’s worth hearing nonetheless, as a demonstration of just how far out Tyner was willing to go at the time.

I know that was a lot; thanks for making it all the way to the end. See you on Friday, when I’ll be asking you to buy some music.

Great thorough overview of the 1970 - 1979 period, thanks!!

Been meaning to look deeper into Alphonse Mouzon's catalog, so this is greatly appreciated!