Stadium Jazz

The art of getting house in an arena

It all started at the 1976 Newport Jazz Festival — but not in Rhode Island. Herbie Hancock was booked into New York City Center, a theater on 55th Street in Manhattan, for a performance that was billed as a retrospective of his career to that point. The show would include mini-sets by his Mwandishi sextet and the Headhunters…but also include a reunion of the 1965-68 Miles Davis Quintet, with saxophonist Wayne Shorter, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams.

Of course, Miles Davis was already into his self-imposed exile at that point, having disbanded his amazing Afro-psych-funk-metal sextet and disappeared into his apartment, where he’d stay until 1981. So when ticket-buyers arrived on the night of the show, there was a sign in the lobby announcing that Davis would not be performing, and that Freddie Hubbard would be appearing in his stead.

It’s hard to imagine two trumpeters more different from each other than Miles Davis and Freddie Hubbard. Davis’s sharp-edged, introverted blues style versus Hubbard’s rafter-raising pyrotechnics… So right away, this was destined to be an entirely different band, despite having four members in common with what had once been. And that’s not even taking into account that it was a decade later, and that all these men had grown and changed as musicians, and that jazz itself had changed around them. One listen to V.S.O.P., the double LP Hancock released after the concert (the initials stand for “Very Special Onetime Performance,” though it’s a play on “Very Special Old Pale,” a designation used to grade cognac), reveals that we’re in a very different realm.

After a solo piano improvisation, the Hubbard-Shorter-Hancock-Carter-Williams quintet launches into a 13-minute version of the pianist’s “Maiden Voyage” that’s massive and bombastic, and incorporates ideas from fusion — at one point, Williams is playing the same relentless hi-hat pattern he laid down all through Davis’s In A Silent Way. They follow that with a five-minute version of Shorter’s melancholy “Nefertiti,” and a nearly twenty-minute version of the Hancock composition “Eye of the Hurricane,” from his Maiden Voyage album (on which Hubbard, Carter, and Williams had all played, with George Coleman — Shorter’s predecessor in the Davis quintet).

Hancock, Carter and Williams reunited the following year for a day-long studio session that yielded two albums: Herbie Hancock Trio, released on CBS/Sony but only in Japan, and Third Plane, released on Milestone in the US, under Carter’s name. Three days later, on July 16, 1977, the V.S.O.P. Quintet, as they were now known, re-convened at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley, CA for the first of two concerts — the second was on July 18, at the Civic Theatre in San Diego — that became the double album The Quintet.

The group was seemingly determined to prove that they were not there to rehash their achievements as the Miles Davis Quintet. The album contains only one relatively less-well-known piece from the Davis repertoire, “Dolores” from Miles Smiles. The rest of the set consisted of two pieces from Third Plane, the title track and the Williams composition “Lawra”; “Jessica,” from Hancock’s Fat Albert Rotunda; Hubbard’s “Byrdlike” (from 1962’s Ready For Freddie) and a new piece, “One of a Kind”; and another Carter composition, “Little Waltz,” from his Piccolo album, also released in 1977. The performances are explosive, a million miles from the abstract free bop they had been delivering a decade earlier. It’s not just their style of playing, either; it’s the sound. Carter’s bass has that gross ’70s rubber-band boing, and Williams sounds like he’s playing on Billy Cobham’s kit, just demolishing the audience with thunderous cannonades. Hancock is sweeping across the keys at breakneck speed, and the horns are going off like Roman candles, one squealing, screaming climax after another. I first encountered the term “stadium jazz” on Ethan Iverson’s site; on Twitter, he said he heard it from bassist Larry Grenadier. I can’t think of a better description of V.S.O.P.’s music than that. This is music meant to be heard in a crowd of thousands, preferably outdoors on a summer night. Within the intimate confines of a jazz club, it would be somewhere between simply overpowering and terrifying.

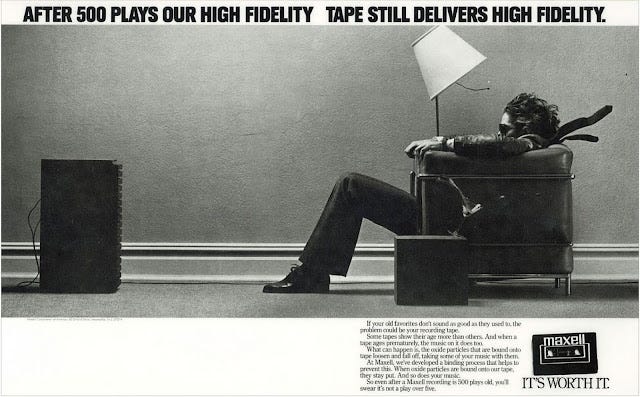

That’s not to suggest that it’s bad music; it’s just big, garish music. V.S.O.P. made two more live albums, Tempest In The Colosseum (recorded just a week after the California concerts, on July 23, 1977 in Tokyo) and Live Under The Sky, from the Japanese festival of the same name in July 1979. The group played on two consecutive days that year, July 26 and 27, and only the first night’s performances were released at first; the second set was appended to a CD reissue in 2004. All of it is well worth your time, as long as you’re in the mood to get blown back in your chair like that old Maxell advertisement.

Tempest In The Colosseum isn’t quite as jacked-up as The Quintet, but it’s still a lot. It’s highly melodic, florid post-bop played in trad style, everybody taking solos one after another in a relatively predictable sequence: horns first, then piano, then bass and/or drums. In addition to tunes they’ve played before (“Eye of the Hurricane,” “Maiden Voyage,” “Lawra”), they deliver versions of Carter’s “Eighty-One,” originally recorded on the Miles Davis album E.S.P., and Hubbard’s fusion hit “Red Clay.” Williams is an absolute avalanche throughout, and on everybody else is going all out, too, of course, except for Shorter, who seems weirdly reticent in comparison with his peers. By this point he’d been in Weather Report for almost a decade, really not playing that much at all, and it feels like he’s still in that same zone of restraint and reticence.

He seems more in the spirit of things at the two concerts documented on Live Under The Sky. The set list is exactly the same on both discs, with some songs shorter on the first night and longer on the second and some the other way around, and everyone’s going big from beginning to end, like they did at the California gigs from The Quintet. And believe me, they get rewarded for it: the audience is screaming as loud as the ones captured on any Seventies double live LP you care to mention — Live Bullet, Kiss Alive, Double Live Gonzo, whatever. One surprising thing about the CD version is that on the second night, there was a short encore: Hancock and Shorter came out, minus the other three, to play a medley of “On Green Dolphin Street” and “Stella by Starlight,” two tunes they played a lot with Miles Davis (there are three versions of “Stella” and one “Dolphin” on The Complete Live At The Plugged Nickel 1965.)

It’s easy to understand V.S.O.P. as a live act; an all-star group delivering powerhouse performances in front of large audiences makes perfect sense — so much so that I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn that it was someone like legendary promoter George Wein, not the musicians themselves, who came up with it. There were several similar all-star acts floating around in the 1970s, including the Giants Of Jazz (with Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt, Kai Winding, Thelonious Monk, Al McKibbon and Art Blakey) and the Milestone All-Stars (Sonny Rollins, McCoy Tyner, Ron Carter and Al Foster) and the CTI All-Stars (Freddie Hubbard, Hubert Laws, Hank Crawford, Stanley Turrentine, Johnny Hammond, Bob James, George Benson, Ron Carter, Jack DeJohnette, Billy Cobham, Airto Moreira). This kind of thing was clearly what festival audiences wanted at the time.

But in addition to all their live recordings, V.S.O.P. also made one studio album — 1979’s Five Stars. It was as much a technological achievement as a musical one. It was a “Master Sound Direct Disk” digital recording tracked on July 29, 1979, two days after the Live Under The Sky festival, and featured just four pieces: Hubbard’s “Skagly,” Hancock’s “Finger Painting,” Williams’ “Mutants On the Beach,” and Shorter’s “Circe.” (Hancock had made two other albums, Directstep and The Piano, the same way in October 1978.) Perhaps because these were one-take performances cut directly to the master, with no editing possible, the performances are more subdued and laid back than any of the live recordings, making this a very nice example of late ’70s acoustic jazz, the kind of thing you could play alongside a contemporaneous Woody Shaw or Dexter Gordon album. The most interesting thing about it, to my mind, is that the original LP and CD versions contained different takes of “Finger Painting” and “Circe”; the differences are subtle, but noticeable if you listen closely. When it was reissued by the Wounded Bird label in 2014 (its first US edition in any format), the CD versions of those two tracks appeared as bonus material at the end.

It’s not hard to argue the virtues of this music. Yes, it’s big, and brash, and it goes for the sweaty climax every time, but I don’t think of those as bad things. They’re populist gestures. And you know what you get when you make populist gestures, as a musician? You get the attention of the public. Look at Kamasi Washington. I’ve said before that if he’d emerged 40 years ago, Washington would have been signed to CTI. And I’ve seen him rock a stadium audience (in Forest Hills, Queens, opening for the band Alt-J). People act like there was no audience for acoustic jazz in the second half of the 1970s. The existence of V.S.O.P., and the Milestone All-Stars and the CTI All-Stars, proves that there absolutely was. Of course, that doesn’t mean record labels knew how to market the music — of all the albums discussed in this post, only Hancock’s V.S.O.P. and The Quintet were released outside Japan at the time. But these days, they’re all on streaming services, so dive in. I think you’ll be glad you did.

Before you go, a few other things:

• Work on The New Book (In the Brewing Luminous: The Life and Music of Cecil Taylor; Wolke Verlag, 2024) proceeds apace. Want to support the project? Join my Patreon.

• I wrote about ISIS’s Oceanic on the occasion of its 20th anniversary, for Stereogum.

• I also published my latest jazz column for Stereogum, which this month includes an interview with Terri Lyne Carrington and reviews of albums by William Parker; Peter Brötzmann and Keiji Haino; Makaya McCraven; The Comet Is Coming; Thumbscrew; and more. Here’s that link.

• Every week, I review a bunch of albums for the Shfl; last week, I tackled three of the most adventurous titles by the (IMO weirdly underrated) saxophonist Joshua Redman; an incredible mid-2010s trilogy by Greece’s Rotting Christ; and some grindcore albums by Resistant Culture, Wormrot, and Defeatist. Link.

That’s all for now. See you next week!