First things first: There’s a new Ava Mendoza/gabby fluke-mogul/Carolina Pérez track out today!

“Amazing Graces” is the second single from their debut album Mama Killa, out today on all streaming services and available for purchase from Bandcamp, Apple Music and Amazon Music.

Mendoza and fluke-mogul have a long-standing duo project, AM/FM, and “Amazing Graces” sounds a little like AM/FM with drums, but that’s underselling it. The guitarist lays down a dirty, slip-sliding blues-rock riff as the violinist takes a soaring solo, and Pérez puts an ass-shaking backbeat underneath it all. Then, in the piece’s second half, it transforms into keening, drumless improv like a hillbilly version of Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music.

Mama Killa will be released on July 11, 2025 digitally and as a limited edition of 500 CDs in heavy-duty gatefold mini-LP sleeves printed on textured paper, with artwork by Burning Ambulance Music co-founder I.A. Freeman. We’re already shipping CDs to customers, so pre-order your copy now!

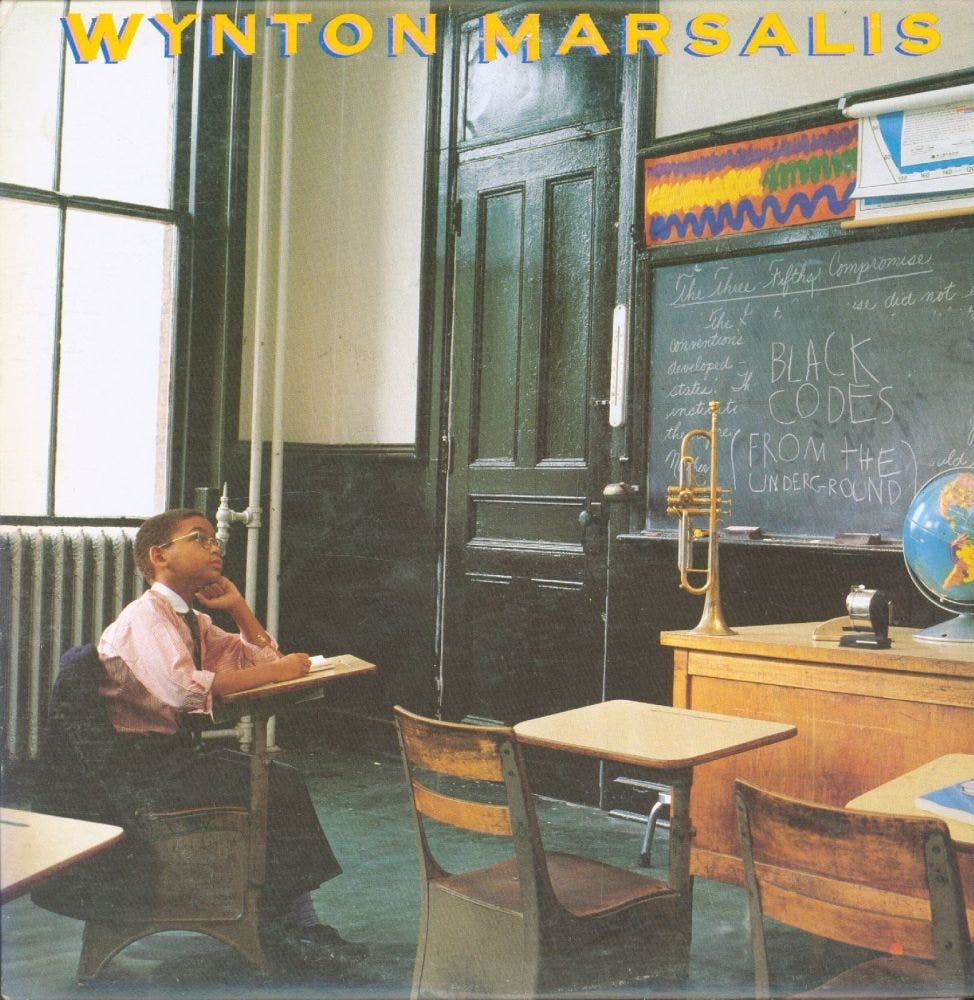

Wynton Marsalis’s Black Codes (From The Underground) was released June 9, 1985. Most people probably think of it as his fourth album, but it was actually his sixth, following 1982’s Wynton Marsalis, 1983’s Think Of One and Haydn, Hummel, L. Mozart: Trumpet Concertos and 1984’s Hot House Flowers and Wynton Marsalis Plays Handel, Purcell, Torelli, Fasch, and Molter. (You need to remember that when he started out, a big part of the hype was that he could play both jazz and classical.)

Black Codes is frequently described as a career high point for Marsalis. It’s definitely a milestone, as it’s the first album to consist almost entirely of his compositions. “Chambers of Tain” is by pianist Kenny Kirkland, but before this, each of his albums had included between one and three originals and a bunch of standards. And it’s probably my favorite of the albums I’ve heard from his large discography, which include J Mood, Live At Blues Alley (which includes performances of two Black Codes pieces), all five volumes of the Marsalis Standard Time series, most of the 7CD Live At The Village Vanguard box, and several recent releases with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra.

Black Codes is a quintet record featuring Branford Marsalis on tenor and soprano saxophones, Kirkland on piano, Charnett Moffett — a teenager at the time — on bass and Jeff “Tain” Watts on drums. Ron Carter plays bass on the track “Aural Oasis”, as he had on the previous year’s Hot House Flowers. This was for the most part a working band, though Marsalis’s previous albums had featured various bassists.

The opening title track features some impressive playing from the brothers, Wynton more than Branford, and explosive drumming from Watts. Kirkland and Moffett assert themselves but are sidelined by everything else that’s going on. The bassist’s sound is thick and buzzy, very much like Charlie Haden sounded when backing Ornette Coleman and/or Keith Jarrett in the ’70s. It’s not my favorite bass sound, but it works well enough here. Wynton’s solo is long, but elegantly structured; Branford’s, on soprano sax, seems less thought-out and more like a collection of ideas strung together. He juxtaposes short, herky-jerky phrases and long squiggly runs, and they’re good and sometimes exciting, but it’s all sort of forgettable once he’s done. There’s a surprising degree of funk to Moffett’s playing, given the context, and that gives Kirkland’s piano solo a powerful groove to ride, his melodies spattering notes like rain falling on a surging ocean.

The second track, “For Wee Folks,” begins with Branford stating the melody, still blowing soprano as his brother plays muted trumpet and Watts keeps the cymbals delicately whooshing. Soon enough, it shifts into a slightly more aggressive gear than the ballad-like intro, though it never gets above a canter. This piece is a blatant imitation of (OK, let’s call it a loving tribute to) the Miles Davis quintet of 1965-68, particularly their early albums E.S.P. and Miles Smiles. No one is specifically emulating anyone else, though Herbie Hancock‘s tinkling style can be heard in Kirkland’s solo and the horns’ interplay has an undeniable Davis/Wayne Shorter feel, even if the latter man never played soprano with the quintet. And of course, Watts is a much heavier drummer than Tony Williams was in 1965 — his playing is more directly descended from what Williams was doing in his “stadium jazz” era, as heard with V.S.O.P.

The third track, “Delfeayo’s Dilemma,” named for another Marsalis brother, bears an even more inescapable resemblance to the work of the Davis quintet; both Wynton and Branford (now playing tenor) seem to be consciously walking in the footsteps of their forefathers. Wynton may be a more technically skilled trumpeter than Davis was (or maybe Davis just knew that technical virtuosity wasn’t the whole game), but his phrasing is often directly derived from the older man’s. This imitative mode continues through “Phryzzinian Man” and “Aural Oasis,” and while nobody embarrasses himself, nothing revelatory happens, either. It’s not until “Chambers of Tain” that the Davis influence is finally shrugged off, and even then, it’s only due to the efforts of the drummer, who takes a solo that’s more influenced by Keith Moon or Ginger Baker than any jazz player. Seriously, it’s crushingly heavy, and the present-day Wynton Marsalis, with his clearly defined ideas about what is and is not jazz, would never have let him get away with all those rolls across the toms.

The album’s final piece, simply titled “Blues,” is one of its most beautiful. It’s a duet for trumpet and bass, nearly five and a half minutes of lyrical phrases and long-held notes — seriously; Marsalis holds one for 22 seconds, midway through the piece — that’s more Louis Armstrong than Davis, as Moffett bounces along behind him, with a more woody, old-school tone than he’s had anywhere else on the record. It’s a great way to end a solid, impressive disc — slightly more mellow than what’s come before, but on the same high instrumental level as everything else. (Interestingly, it wasn’t listed on the back cover of the LP, only on the disc labels. Was it a last-minute addition, the way “Train In Vain” was tacked onto the Clash’s London Calling too late to appear on the sleeve?)

Black Codes (From the Underground) doesn’t shatter any boundaries, but I don’t want it to. I respect Wynton Marsalis’s conservatism. He serves a purpose. Somebody has to maintain walls, if breaking through them is to have any meaning. But I do wonder what his ultimate legacy will be.

None of these tunes — or any of his many, many compositions — has become a standard. I know of only one recording of his music by someone else: trumpeter Nate Wooley’s (Dance To) The Early Music, an entire album of Marsalis pieces which features versions of four Black Codes tracks. (It’s not available on Bandcamp, but you can get the CD from the label.)

Black Codes was remastered in 2023; you can hear the upgraded version on streaming services, or buy it digitally, but it wasn’t reissued in physical form. Even if you think you don’t like Wynton Marsalis’s music, give it at least one listen. I’ve found myself coming back to it much more often than I ever anticipated.

That’s it for now. See you on Friday, when we’ll be talking about the other guitar-violin-drums trio release on Burning Ambulance Music, Breath Of Air’s self-titled album.

Good reminder of an album that defined a certain era. Black Codes is great, and I think has more originality, especially rhythmically but also compositionally, than you give it credit for. I saw that band at the Village Gate and they weren't fooling. Watts was tremendous in Branford's band as well.

Before Black Codes, Think of One was a very attractive album, and after it, J Mood was also very nice, emphasizing a slow burn feeling with Marcus Roberts on piano. The quartet albums, with Roberts, Robert Hurst, and Watts, were all about the complex virtuosity, which was kind of thrilling.

I remember how baffling "The Majesty of the Blues" was when it came out in 1989. The long, unlistenable sermon written by Crouch killed it for me. But I saw that early sextet in concert too and they sounded gorgeous. Wynton's bands have always had rhythm sections of the highest order, and they often save the less successful music from dullness. Reginald Veal and Herlin Riley, wow. Riley had already spent time with Ahmad Jamal before joining Wynton.

But both Wynton and Marcus Roberts got stuck into a kind of stodgy attitude, lecturing about the eternal verities and the hushed reverence that must be afforded the great masters. I feel this has gotten in the way of their more personal contributions, which can be superb. They get bogged down in anxiety about proving their correct positioning in The Tradition. Anyway, not simple. Thanks for bringing up the importance of the Black Codes band.

Black Codes is great. Standard Time Vol 1, house of tribes great. For Branford, Crazy People Music is great. Crazy that with Wynton we have less than 10 years of this small group period and then 30 years of the Duke/big band/large works period. I would love a Wynton unaccompanied solo album! or works for trumpet and piano. or anything...other than big band and orchestra works.

Looking back at the big picture, man, the 60s went by so fast, Miles's 2nd quintet went by so fast. It was good that people returned to dwell on that style a bit. In jazz we are all still living in the 60s in a way...