It’s been quite a year. 2023 was a period of major transition and evolution for me. Let’s start with the biggest one: My wife and I left New Jersey in March, and now we live in rural Montana, where we are absolutely thriving. The peace and quiet alone has done wonders for our creativity, and new opportunities have flowed in the door since our arrival.

Beyond that, as regular readers know, I finished writing my next book, In the Brewing Luminous: The Life and Music of Cecil Taylor. It’ll be out sometime next year via Wolke Verlag in Germany (in English).

I also wrote a bunch of things for print and online outlets, though not as many as in past years. I profiled pianist Simona Premazzi and saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock for DownBeat; wrote about the 20th anniversaries of Zwan’s self-titled album and Metallica’s St. Anger and the Mars Volta’s De-Loused in the Comatorium for Stereogum, in addition to continuing my monthly jazz column, Ugly Beauty; interviewed trumpeter Susana Santos Silva, techno legend Ken Ishii, and RogueArt label head Michel Dorbon for Bandcamp; wrote cover stories on drummer Dave Lombardo and free jazz quintet Irreversible Entanglements for The Wire; and reviewed the Deutsche Grammophon Avantgarde Series box set for Universal Music’s website.

If you read any of that stuff during the year, I’m grateful to you, and I hope you got something out of it. There’s transition underway in my little corner of music journalism: The Wire will have a new editor next year, for the first time in eight years, and Bandcamp Daily will likely change the scope and tone of its coverage, since more than half its editors (including the ones I worked for the most) were laid off. All I can really say for sure is that this newsletter will continue.

Next week’s newsletter, FYI, will be the Year-End Roundup, a list of the 50 best albums I heard between July 1 and the end of the year. Then I’ll take a week off, and be back on Wednesday, January 3, 2024.

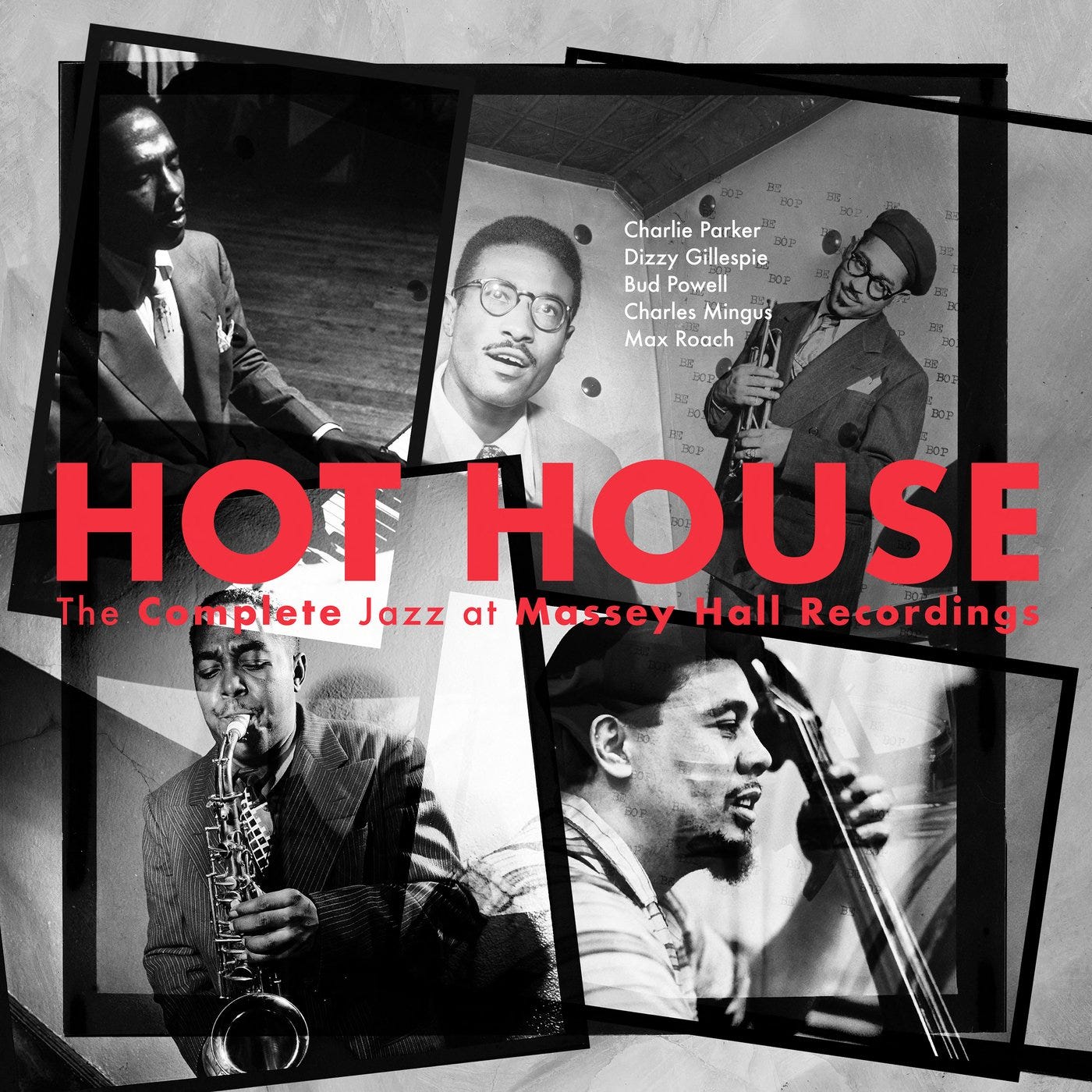

Jazz at Massey Hall is a live album that was recorded in 1953 in Toronto by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach. It’s the only recording to feature all five musicians, and the last recording by Parker and Gillespie. As such, it’s often described as one of the greatest jazz albums ever, and regarded as a crucial document. The original LP contained six tracks, with overdubbed bass. (Mingus thought he wasn’t loud enough, and the record was coming out on his own Debut label, so…) There were another six songs recorded at the actual concert, featuring just the Powell/Mingus/Roach trio, plus a drum solo. That material came out separately. Now, in celebration of its 70th anniversary, the concert has been remastered and reissued in full as a 3LP or 3CD set, Hot House: The Complete Jazz At Massey Hall Recordings. The first disc is the original LP, minus Mingus’s overdubbed bass (and he’s clearly audible throughout — he even gets a solo on “Hot House”!); the second disc is the drum solo and the Powell trio material; and the third disc is the version of the quintet material with the bass overdubs.

The quintet set consists of “Perdido,” “Salt Peanuts,” “All the Things You Are” combined with “52nd Street Theme,” “Wee” (aka “Allen’s Alley”), “Hot House,” and “A Night in Tunisia.” The announcer says the band will take a short intermission, and when the show starts up again, Max Roach takes a solo, billed as “Drum Conversation,” after which the trio performs “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” “Embraceable You,” “Sure Thing,” “Cherokee,” “Hallelujah” (not the Leonard Cohen song, although this concert did take place in Canada), and “Lullaby of Birdland.”

The recording is weird. Although it’s all from one concert, the sound is quickly faded down and back up again between tracks, and the audience sounds overdubbed. (The concert has always been described as under-attended, because there was a big boxing match the same night, but there’s a lot of enthusiastic response, especially during Max Roach’s drum solo.) Also, the recordings of just the trio seem to be of inferior quality when compared with the recordings of the full quintet. Maybe that’s because the horns were miked better than everybody else, I don’t know.

Anyway, listening to this mostly makes me think about why Charlie Parker’s music has never had the impact on me that it has had on so many others. Like, I can hear that he’s a virtuoso player, and I acknowledge his influence — he changed the way players after him approached composition, improvisation, and even their tone on their instruments. But any time I read about Parker being called the greatest saxophonist ever, or whatever, I always think Sure, for one particular value of “great.”

His melodically and harmonically adventurous, chord-flipping style (which he famously described as “playing clean and looking for the pretty notes”) is one way to play jazz. But it’s not the only way, by any means. Personally, I have always been more drawn to players with more rawness and grit to to their sound. And I don’t just mean free jazz. A lot of what Albert Ayler, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp and others — even more mainstream players like Sonny Rollins and Joe Henderson — did in the 1960s was following in the footsteps of players like Illinois Jacquet, Big Jay McNeely, Red Prysock, Arnett Cobb, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis and others. And that kind of music has always had a greater appeal to me than the slippery instrumental one-upmanship (Thelonious Monk, easily the greatest composer the movement produced, said, “We’re going to create something they [meaning fellow musicians] can’t steal, because they can’t play it”) of bebop. I think Jimmy Lyons is a hugely important figure, because he was able to take bebop ideas and import them into “free” or “avant-garde” settings. (I put “avant-garde” in quotes there because bebop itself was 100% avant-garde music when it first developed, in the 1940s.)

Charlie Parker was playing publicly as early as the mid-1930s, but didn’t break out on record until 1945, because of a World War II-era recording ban, and he died in 1955. He was hugely influential and inspirational during the roughly ten-year period that he was a major figure, and bebop was a fascinating phenomenon. Almost punk in its speed and aggressiveness, but extraordinarily demanding on a technical level, it was kind of a music-school thing. It’s the kind of music you get when a bunch of young, talented men get together in a room, night after night, and start showing off for each other. “Listen to what I came up with!” “Oh, yeah? Well, how about this?” And on and on, at lightning speed. Which is exactly why it continues to appeal to many young jazz musicians.

The Massey Hall concert was kind of the period at the end of the bebop sentence, though. The style was no longer any kind of revolution by 1953; in fact, all of its key ideas had been established by 1948, and sometimes I feel like its true legacy might be the pervasive attitude among jazz musicians that it’s the audience’s fault if they don’t like what they’re hearing. It was yesterday’s future. Personally, I’d rather listen to a lot of other things by Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach, and I just…don’t listen to Charlie Parker very often, and Bud Powell even less. But if you’ve never heard this concert — and there’s no reason why you should have! It’s from 70 years ago! — Hot House: The Complete Jazz at Massey Hall Recordings is worth checking out at least once.

That’s it for now. See you next week! Except for you, paid subscribers — stick around after the paywall!

Paid subscribers only: Thank you as always for your support. Your subscription entitles you to free downloads of titles from the Burning Ambulance Music catalog. So if there’s anything on our Bandcamp page that you haven’t heard and want to hear, email me and let me know, and a code will be on its way to you!

If you like what you hear, please — spread the word. The music business is pretty much a smoking crater, as all of us who still love music know too well. Word of mouth from a trusted source is better than any advertisement. Thanks!

Hi Phil, I enjoyed reading this, there's some i agree with and some i disagree with, however, with all due respect, i would pretty strongly disagree with reading bebop as a "music school thing" and being born from people just showing off and trying to burn each other with more and more skill and language. I actually think the textural, aesthetic, and conceptual aspects of bebop are under-appreciated, and there's a lot that can be related to free music and creative improvised music.

I strongly support the fact that bebop in general and Charlie Parker in specific don't appeal to you. Something I've learned over many decades of listening to jazz (I also play jazz and write about it), is that no matter how much an artist is interesting and worthy, I vote with my ears. Meaning: as interesting as it may be, I seldom listen to that artist or recording. I tend to say "it doesn't suit me "or "it's not for me."

Another thing I've learned to do is to nott project or psychologize where an artist is coming from or why an artist does something if the artist has not specifically said so.

You write that bebop:

was kind of a music-school thing. It’s the kind of music you get when a bunch of young, talented men get together in a room, night after night, and start showing off for each other. "Listen to what I came up with!” “Oh, yeah? Well, how about this?” And on and on, at lightning speed. Which is exactly why it continues to appeal to many young jazz musicians.

That does not strongly describe bebop to me. I know that some of the young musicians are who participated in the jam sessions at Minton's were competitive, but many were not, and that competitiveness was strongly in place during the swing era, according to some accounts a musicians of that era. (I'm referring to the tradition of "cutting contests.")

Ironically, what you describe at the end of that passage describes prevalent attitudes in today's musicians who come out of jazz studies programs at universities and conservatories! I taught at the University Of Oregon school of music for many years, and I've seen that unfortunate attitude from a fair number of young jazz students very often, and they're playing exemplifies that. And, speaking of Parker, they may have learned some Charlie Parker licks and solos, but they miss the whole emotional side of his music! And, bebop does not really appeal to those young players – – saxophonist would rather sound like Mark Turner than Charlie Parker.

Thank you for your posting!