I wasn’t surprised to hear that German saxophonist (and visual artist; never forget that he was a painter and sculptor first, an assistant to and friend of Nam June Paik in the early ’60s, and designed almost all of his own album covers in a unique, blocky, instantly recognizable style) Peter Brötzmann had died — last week, in his sleep, at home in Wuppertal. He’d been ill for some time with a serious lung condition that got worse during the pandemic; and after a short string of European dates he suffered a major health crisis, offering the following update on social media (in all caps, as was frequently his style):

“YES, I HAD A COMPLETE BREAKDOWN COMING HOME FROM WARSAW AND LONDON AND YES, EMERGENCY, RE-ANIMATION, INTENSIVE CARE AND YES, OUT OF HOSPITAL SINCE 10 DAYS AND TRYING TO ORGANISE MY DAILY LIFE AND NO, I HAVE NO IDEA WHAT THE FUTURE WILL LOOK LIKE AND NO, I WON’T BE ABLE TO PLAY IN THE (NEAR) FUTURE, MEANS NO TRAVEL AND NO STAGE. NO GOOD NEWS, MY FRIENDS, BUT IT IS HOW IT IS AND YES, I WILL DO MY BEST TO STAY WITH YOU IN WHAT FORM AND FUNCTION EVER. ALL GOOD AND NOTHING TO COMPLAIN, BEST TO YOU ALL b”

When I emailed him in May with some questions for what became this post, he began his reply by saying “the health is very shaky and it won’t get better that’s why I make it short”.

Still, something can be unsurprising and still an almost physical shock. The power of Brötzmann’s music made him seem like someone who’d live forever. Of course, we all thought that about Lemmy, too…

I’ve been listening to Brötzmann for almost 30 years. I’m pretty sure the first album of his I heard was Last Exit’s The Noise of Trouble (Live in Tokyo), sometime in the early ’90s. It’s not their best work, but it was what I could find at the time. The first time I saw him live was January 21, 1997 at the long-defunct NYC venue the Cooler, a concrete basement in the meat-packing district. He performed with fellow saxophonist Thomas Borgmann, bassist William Parker, and drummer Charles Downs, then known as Rashid Bakr. There was no stage; that alone felt revolutionary to 24-year-old me, still accustomed to the dynamics of rock shows and traditional jazz clubs, where the band was up there and you stood (or sat) politely over here. These guys were on the floor and wailing, and the sound bounced off the unforgiving walls in what felt in the moment like a searing, rattling, sustained scream.

Their set — roughly 50 minutes of music, divided into two long tracks — was released as The Cooler Suite in 2003. Listening to the CD years later, a much more nuanced and thoughtful performance was revealed. Parker and Bakr were laying down a thick, energetic groove, the drummer eschewing time in favor of a tense, shivering pulse as the bassist bounced loud and hard, his strings booming and bonging like cables struck with a hammer. The two saxophonists took turns soloing, only occasionally harmonizing at the points where one man was passing the baton to the other like relay racers. Brötzmann’s playing was more based in long, hoarse cries than Borgmann’s; the latter man opted for fast flurries of notes that got grittier as he came to the end of a phrase. But they were both clearly steeped in the blues and forged in the flames of 1960s free jazz.

The second (and, sadly, final) time I saw Brötzmann live was at Tonic, another NYC venue long gone now, sometime in the early to mid-2000s. He was performing with his quartet Die Like A Dog, with the late Toshinori Kondo on electronically manipulated trumpet, Parker on bass, and Hamid Drake on drums. Again, it felt like a solid wall of sound in the moment, though I remember distinctly that it had the feel of trance music as well; Brötzmann loved to let Parker and Drake set up a groove and ride it for what could seem like hours, or like time had stopped entirely. I’m sure that if there was a recording to refer back to, subtleties would emerge. They always do. Every time I listen to a Brötzmann recording, I’m confronted with something I hadn’t noticed before, either the way he carefully alters a phrase he seems to be just repeating, or the way he adjusts to a small shift in the rhythm, or the way he makes room for other players to be heard.

Brötzmann’s music was misunderstood for almost his entire career. He’s been described as a tyrannosaurus, a flame thrower, a blast furnace, an unfettered fire-breather, and his music is sold as if it’s a nonstop explosion. In truth, though, he was often an intensely lyrical player, with a deep sense of what his bandmates were doing and a love of true communication. In 2018, I spoke to bassist Marino Pliakas and drummer Michael Wertmüller of his long-running trio Full Blast about working with him. The bassist said, “Peter’s always got big ears and is very much hearing and interacting. If his co-players are not able to oppose something, then he just plays, of course. But with Michael and myself, it’s almost a jazzy approach, depending on each other and listening and firing at each other and stopping together and hearing crossfades. In my opinion, he’s a very good listener.”

A year later, I interviewed the man himself, when he released I Surrender Dear, a solo album of jazz standards and blues tunes. At that time, he was quite eager to discuss his love of classic jazz, saying, “If I’m playing at home, for example, I usually play standards and things like that, just to practice and get the sound right…When I’m walking around or in a new city and strolling through the streets, I’m always whistling, and it always comes [back] to some of these old songs.” Our full conversation became episode 49 of the BA podcast; we talked about the music he heard growing up in Germany in the ’50s, about his visual art, about how he chose his collaborators, and much more.

Brötzmann’s catalog is vast, and I’ve heard a lot of it but by no means all of it. I’m going to run down the stuff I’m most familiar with below, in order to give potential new listeners a road map of sorts. A lot of this is available on streaming services, and a lot more is available on Bandcamp, mostly here and here.

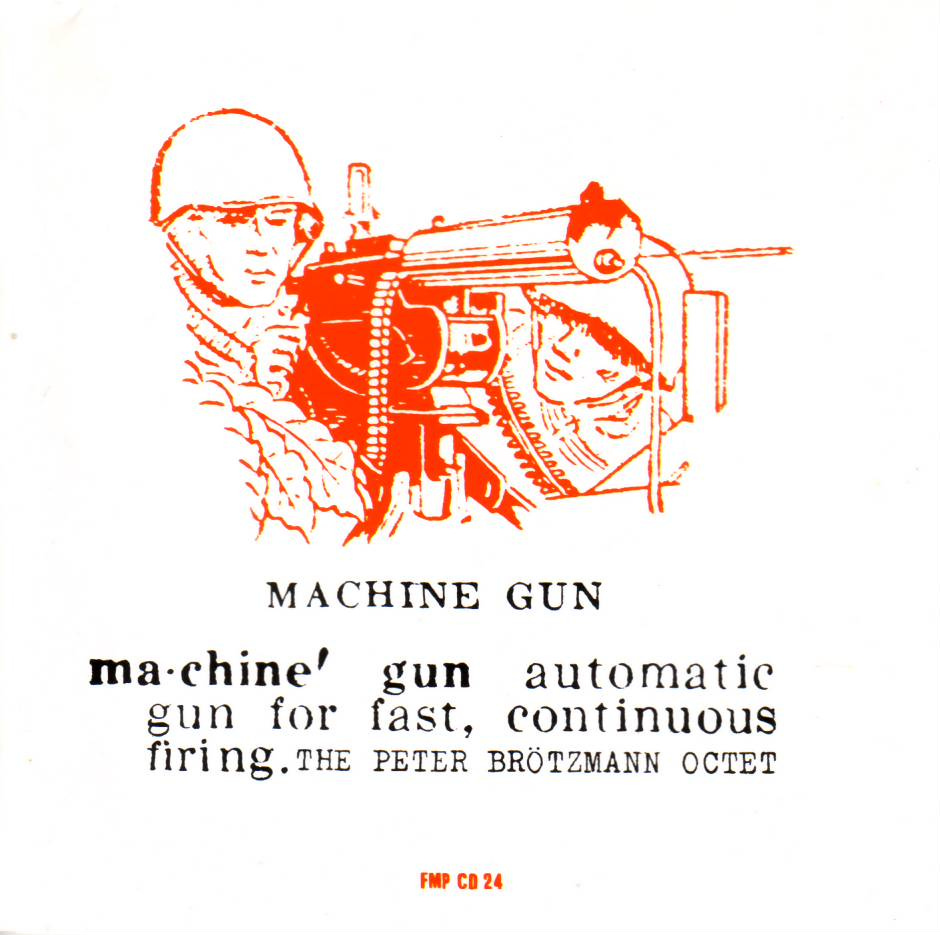

Early work: Look, Machine Gun — a 1968 octet session with three saxes, piano, two basses and two drummers — is legendary for a reason. It’ll tear your face off the first time you hear it. But the second time, you’ll notice how structured and riff-based it is, and how surprisingly sensitive the interplay between the members is. Nipples and More Nipples are both from a set of April 1969 sessions, though More wasn’t released until 2003. They’re even wilder, full of clatter and scrawl; guitarist Derek Bailey, present on one track from each disc, is a particularly potent antagonist. Fuck De Boere features a 10-piece band (three saxes, four trombones, guitar, keys and drums) blasting away in 1970, plus a live version of “Machine Gun” that predates the album session, and it too will take the paint off your walls.

Brötzmann/Van Hove/Bennink: Pianist Fred Van Hove and Dutch drummer Han Bennink were Brötzmann’s partners in a trio that lasted several years but did a lot of its best work early on. Live in Berlin ’71 is three LPs turned into a 2CD set, with trombonist Albert Mangelsdorff guesting. Balls and FMP130 (named for its catalog number) are studio recordings that got fiery at times but had much in common with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, too: lots of unexpected percussion and dramatic silences. Jazz In Der Kammer Nr. 71 is a live archival recording from 1974, recently unearthed.

Last Exit: In 1986, bassist/producer Bill Laswell assembled this “supergroup” with Brötzmann, guitarist Sonny Sharrock, and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson for a string of European dates. They hit stage with no preconceptions and pumped out a truly stunning blend of free jazz, punk, funk, and blues, played at top volume and breathtaking speed. By 1989 it was all over, but a string of live albums — Last Exit, Köln, Moers (featuring guests Billy Bang and Diamanda Galás) and The Noise of Trouble: Live in Japan (with Herbie Hancock(!) and Akira Sakata) from the first rush, Cassette Recordings ’87 from the following year, and Headfirst Into the Flames a farewell from 1989 — proved just how hard you can go. Iron Path is a Laswell studio creation featuring the members of Last Exit, polished but still exciting, and Low Life is a collection of duos: Brötzmann on bass sax, Laswell on bass, gut-churning but surprisingly tender. You might also want to track down No Material, a live disc by a very short-lived group featuring Brötzmann, Sharrock, and drummer Ginger Baker, plus a few others.

Full Blast: In 2006, Brötzmann formed this trio with fretless electric bassist Marino Pliakas and drummer Michael Wertmüller. They lived up to their name, delivering a high-energy brand of punk/metal squall that exploded from the speakers, but upon repeated encounters revealed a surprisingly sympathetic interaction between members. Their self-titled debut, 2009’s Black Hole/Live In Tampere, and Risc, on which the music was subject to electronic editing and manipulation, are all essential. They also expanded the group at times; on Crumbling Brain, they were joined by trumpeter Peter Evans, saxophonist Mars Williams, and guitarist Keiji Haino, and on Sketches & Ballads they brought in trumpeter Thomas Heberer, saxophonist Ken Vandermark, and percussionist Dirk Rothbrust for a surprisingly subtle chamber jazz work.

Die Like A Dog: This quartet was one of Brötzmann’s most interesting projects of the mid to late 1990s. It featured trumpeter Toshinori Kondo, whose instrument was frequently fed through racks of electronics, bassist William Parker, and drummer Hamid Drake. (For one 1998 gig, documented on From Valley To Valley, Roy Campbell subbed for Kondo.) On their 1994 self-titled debut, they incorporated themes from Albert Ayler compositions, but their music quickly evolved into its own thing — a kind of endless (pieces frequently lasted 45 minutes), free-flowing trance groove with Kondo’s solos amorphous and warped, and Brötzmann’s alternately squalling and tender. The two-volume Little Birds Have Fast Hearts, Aoyama Crows, and Close Up are all brilliant, float-away-on-a-river-of-sound experiences. Never Too Late But Always Too Early is a 2CD trio set featuring just Brötzmann, Parker and Drake, but has a similar feel.

Solo: The quickest way to understand any musician’s language is to hear them deliver a monologue. Brötzmann loved collaboration, but he released multiple solo albums, and they’re often fascinating. He plays a wide variety of horns, and you can really hear him thinking. No Nothing, from 1991, is particularly meditative — there are times where you could wrong-foot someone by asking them to identify the player. Right as Rain, from a decade later, is a dedication to his late friend and fellow saxophonist Werner Lüdi, and is also drenched in melancholy. I Surrender Dear, released in 2019, is an all-tenor sax collection of ballads, blues, and uniquely Brötzmannian interpretations of jazz standards like the title track, “Lover Come Back to Me,” and “Nice Work If You Can Get It.”

Key collaborations: As I just mentioned, Brötzmann loved to collaborate with other musicians, to hear what they had to offer and counter with his own explosive ideas. He played all over the world, with people from all sorts of backgrounds and musical perspectives. Some of my favorite releases in this category are The intellect given birth to here (eternity) is too young, a 4LP set of live duos with Keiji Haino from 2018; the currently hard-to-find but astonishing Nothing Changes No One Can Change Anything, I Am Ever-Changing Only You Can Change Yourself, a 3CD live recording with Fushitsusha; An Eternal Reminder of Not Today/Live at Moers, on which he guested with the brilliant noise-blues band Oxbow, disguising himself as a sort of hellish Clarence Clemons; Historic Music Past Tense Future, a live recording from 2002 at CBGB(!) with William Parker on bass and Milford Graves on drums; and last but certainly not least, a self-titled collaboration with Portuguese stoner-rock trio Black Bombaim that’s easily one of the heaviest things he was ever involved with.

There’s plenty of other Brötzmann material I’ve never heard. He had a reeds-only trio with Ken Vandermark and Mats Gustafsson called Sonore that I’ve never checked out. His long-running large unit, the Chicago Tentet, put out a pile of records, and I’ve only heard one or two. In his last few years, he embarked on a series of duos with lap steel guitarist Heather Leigh which have been highly touted, and I need to dig into those. So although the man himself is gone, the immense body of work he left behind will be feeding fans and subsequent generations of musicians for a long, long time to come. And I suspect that’s exactly how he’d want it. In 2016, he famously said, “I have hope for the very young people, that they can change the music. They still call me avant garde, but I’m 74! What kind of shit is that? That’s terrible. People who are 24 should be the avant garde!”

Shortly before his death, he gave an interview to Die Zeit, which you can read at this link. (It’s in German, but Chrome, at least, will give you the option of translating it into English.) It ends with him saying, “I’m 82 now, I’ve had an eventful life and I’ve never taken it easy. If blowing doesn’t work anymore, then I have to concentrate on the fine arts again. Just stopping is out of the question.” Not bad, as last words go.

I saw him play with Yagi Michiyo in a basement at some university in or near Tokyo. I was actually mostly there to see Yagi, and I had no idea what PB sounded like. The stuff they recorded together is also great but it doesn't compare to the sheer power of that show (as I remember it).

Beautiful summary of career that's bigger than life. He could confound the listener, myself included, but when he connected ... WOW. You take the risk, go for the ride, and hope you survive. Avant garde to the end.