First Things First: I have created a standalone Burning Ambulance Music website, for people who don’t want to deal with Bandcamp. Our CDs are $2 cheaper there than anywhere else — Bandcamp, Amazon, or any other webstore. So buy direct!

As an extra inducement, I am launching a limited-time-only Buy One, Get One Free promotion. See, I have a bunch of CDs from other labels sitting here. I’m not gonna tell you what they are, but if you’re a fan of the music we cover, you’re likely a fan of these artists, too. If you buy any Burning Ambulance Music CD direct from our new website, I will stick one in the envelope as a Bonus Mystery Disc. Thanks!

I’ve been mildly obsessed with South African jazz for about the last five years. It helps that the scene seems to have been undergoing a renaissance. There’s a young (in jazz terms) school of players like pianist Nduduzo Makhathini, trumpeter Ndabo Zulu, saxophonist Sisonke Xonti, keyboardist Thandi Ntuli, bassist Herbie Tsoaeli, drummer Ayanda Sikade, and others who’ve been making incredible records, together and separately. I’ve reviewed a lot of them (and interviewed some of the artists) for Stereogum, for Burning Ambulance, and even for Bandcamp Daily. But listening to new albums has drawn me into the music’s past, too, as is often the process with jazz. And this month, three rare albums from the 1970s have been reissued, all of which are worth your time and money.

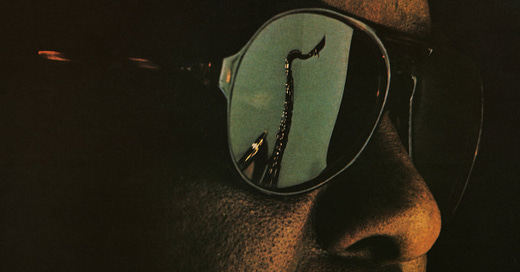

Saxophonist Mike Makhalemele (1938-2000) made a string of albums in the 1970s, blending jazz, funk, disco and African grooves and mixing original tunes with versions of pieces by Herbie Hancock, Bob James, and Grover Washington, Jr. The Peacemaker, released on the Jo’burg label in 1975, was his debut. It’s a short album — four tracks in 26 minutes — featuring keyboardist Jabo Nkozi, bassist Sipho Gumede, and an unidentified drummer. The reissue adds one bonus track, “Peace Train,” culled from a contemporaneous compilation. It’s very much in a soul jazz mode, opening with the funky “Going West” and continuing with the midtempo “End of the Road,” which gives Nkozi as much solo space as the leader. The second side kicks off with “15th Avenue,” another vamping tune that really makes me wish the drummer’s name was listed in the credits, because his hammering funk breaks are the kind of thing hip-hop DJs have been feeding off for 50 years. The last track, “My Thing,” is more of the same. Makhalemele has a big sound and a way with a melody, and the grooves the band is laying down are pure ’70s soul. If you like Bob James, Grover Washington, Jr., Stanley Turrentine, or Hank Crawford, you’ll like this album.

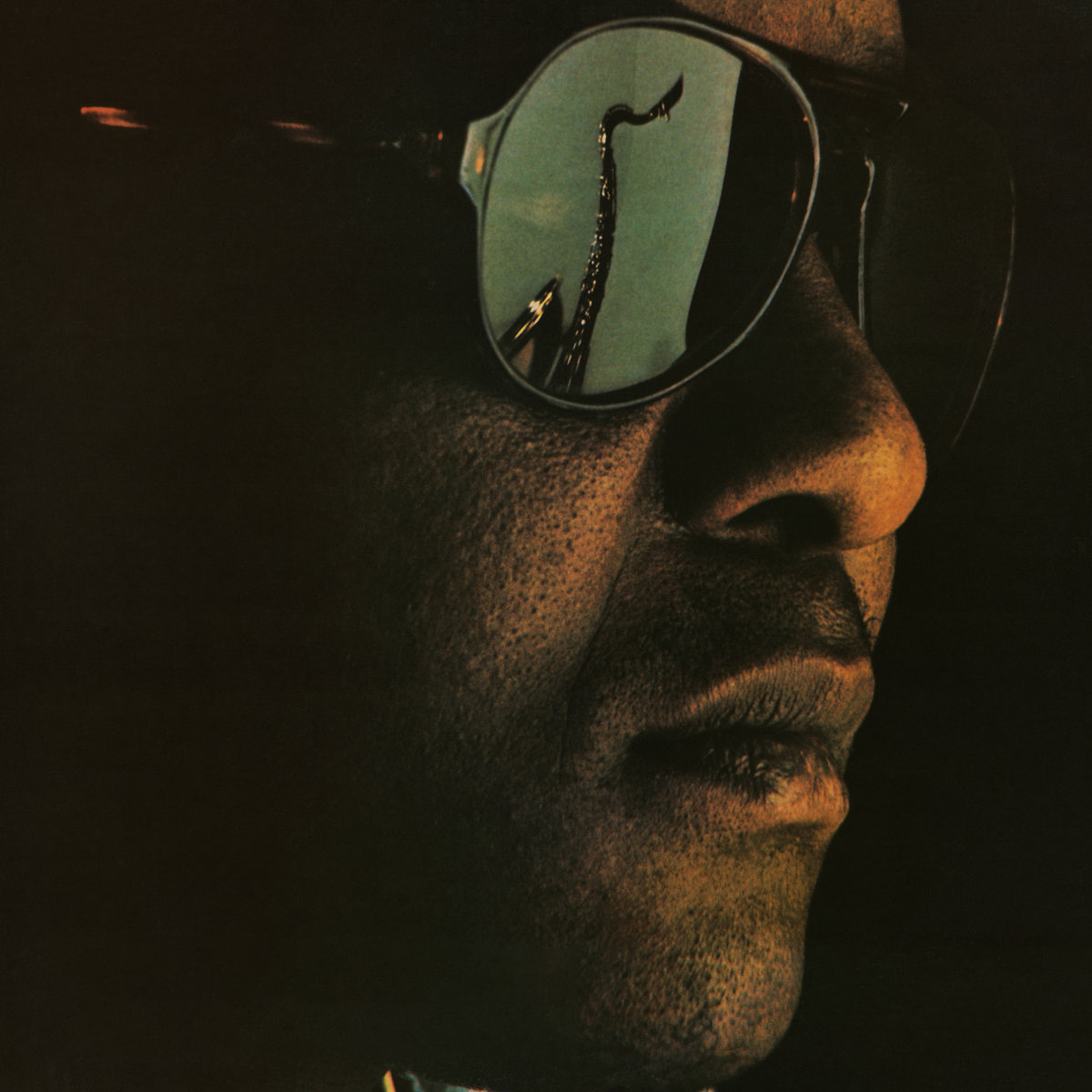

Winston “Mankunku” Ngozi (1943-2009) was a key figure in the development of South African jazz as its own thing with a specific cultural context. His 1969 album Yakhal’ Inkomo was inspired by American jazz, but also by conditions in South Africa at the time. The title translates to “the bellow of the bull,” a metaphor for resistance to oppression that slipped under the radar of the apartheid government. But the album’s second track, a Ngozi original, is called “Dedication (to Daddy Trane and Brother Shorter),” and the album also includes versions of Horace Silver’s “Doodlin’” and John Coltrane’s “Bessie’s Blues.” Alex Express marked his return to the studio, backed by the Cliffs, a band featuring Stompie Manana and George Tyefumani on trumpets, Roger Khoza on organ, Allen Kwela on guitar, Philip Kiti on bass, and Peter Jackson on drums. Like The Peacemaker, it’s a short record: five tracks in just 25:57. But it’s so energetic and alive, that’s all you’ll need. Practically the polar opposite of the stark, muscular Yakhal’ Inkomo, Alex Express is a celebratory soul jazz album that reminds me of Larry Young at times and King Curtis at others.

In 1976, Makhalemele and Ngozi met in the studio, for the collaborative album The Bull and the Lion. Just three tracks long, but running a comparatively epic 28:19, the disc featured the two saxophonists backed by three members of a South African pop/rock band of the time, Rabbitt, as well as pianist Tete Mbambisa. The Rabbitt musicians were bassist Ronnie Robot, drummer Neil Cloud, and guitarist Trevor Rabin, the latter of whom would later become a member of Yes and a well-known pop producer and soundtrack composer. This is a very 1976 album, slick and polished and almost nudging into disco territory at times; the backing band has a real cruise-ship vibe on “Snowfall” in particular. But you have to put the music into context — this was South Africa in 1976, and the three members of Rabbitt (who also deliver backing vocals on the 14-minute closer, “Rainy Day”) were white, while Makhalemele, Ngozi, and Mbabmisa were not. Such a thing may not even have been legal, and was almost certainly frowned upon. So the fact that this music exists at all is amazing, and makes the players’ decision to go for a slick, urbane sound rather than some kind of raw-lunged protest jazz seem even braver. The message becomes “why can’t we just party together?”, which can be a revolution all its own.

That’s it for now. See you next week! (Buy some CDs!)

thanks for sharing these gems!