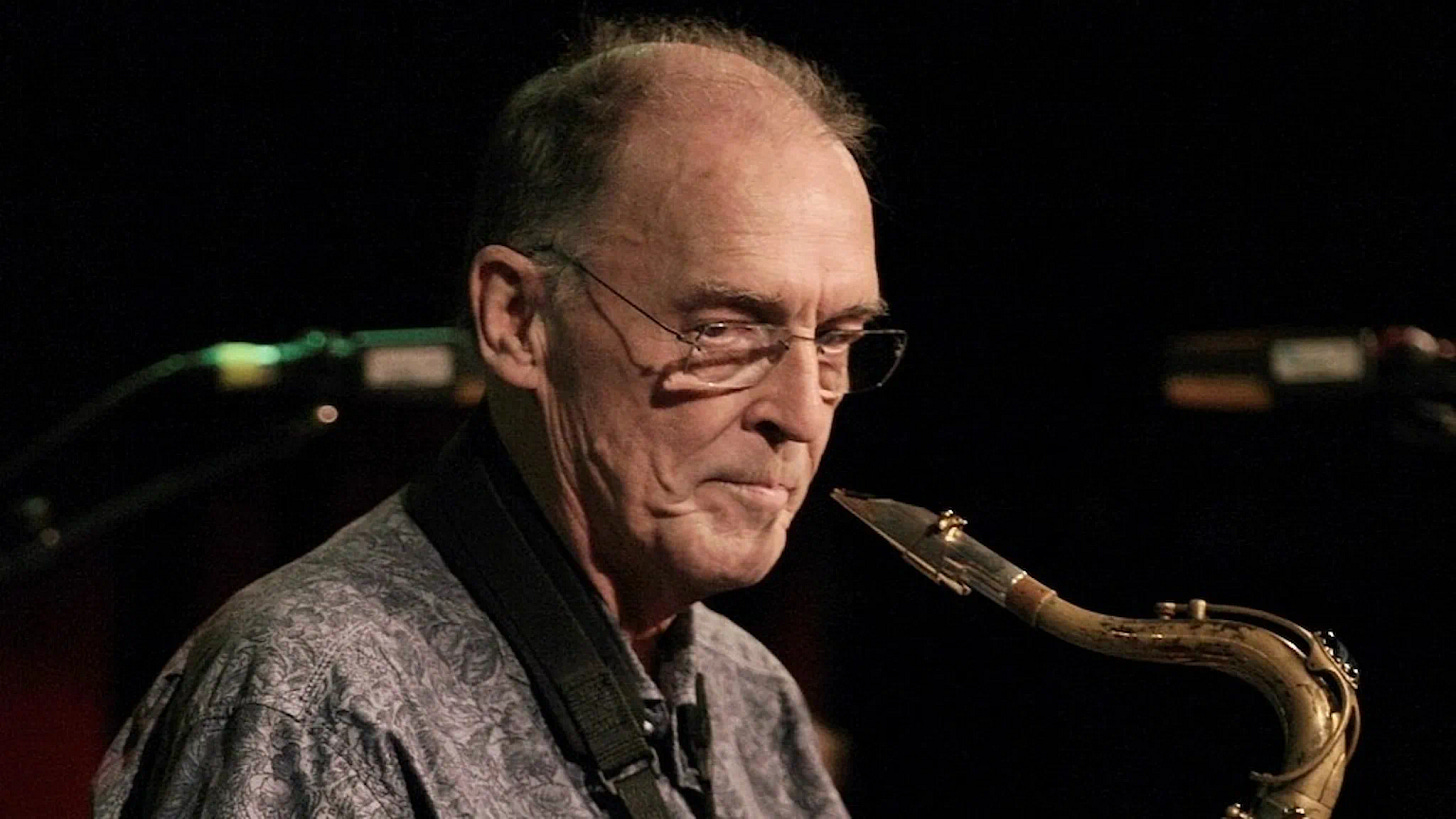

Swedish saxophonist Bernt Rosengren died last week at 85. Born on Christmas Eve 1937, he was one of the most important figures in Nordic jazz. As this Göteborgs-Posten obituary points out, he won the Swedish jazz magazine Orkesterjournalen’s Golden Disc award (roughly akin to Album of the Year) five times, in 1965, 1969, 1974, 1999 and 2009, and has been called “the godfather of Swedish jazz.”

His first recordings were made in 1957, for the Swedish label Dragon, as part of the group Jazz Club 57 with pianist Claes-Göran Fagerstedt, bassist Torbjörn Hultcrantz, and drummer Sune Spångberg. The following year, he played the Newport Jazz Festival as part of an ensemble called the International Youth Band that also featured trombonist Albert Mangelsdorff, pianist George Gruntz, and guitarist Gabor Szabo, among others. In 1962, he got a major break when he was brought in to collaborate with Polish pianist Krzysztof Komeda on the soundtrack to Roman Polanski’s film Knife in the Water.

Rosengren’s sound was enormous, but controlled. He was one of the classic “big horn” players of the 1960s, in the lineage of John Coltrane and Dexter Gordon, with Coltrane’s intensity and questing phraseology and Gordon’s deeply bluesy tone. But his interest in music from around the world, particularly North Africa and the Mediterranean, drew him to embrace surprising timbres and give his playing a keening, desert-like tone at times. When he returned to his roots in the 21st century, recording for over a decade with a quartet he maintained until the end of his life, the journeys he’d undertaken decades earlier allowed him to make seemingly old-fashioned tunes new.

Beginning in the late ’60s and extending into the mid ’70s, Rosengren formed crucial alliances with like-minded musicians from the US, the Middle East, and South Africa. He was part of the ensemble on my favorite Don Cherry album, 1969’s Eternal Rhythm, alongside trombonists Albert Mangelsdorff and Eje Thelin, guitarist Sonny Sharrock, vibraphonist Karl Berger, pianist Joachim Kühn, bassist Arild Andersen and percussionist Jacques Thollot. Its two side-long suites clang and moan, with tootling flutes, crashing cymbals, and wailing horn outbursts that turn free jazz into a kind of communal theater. Rosengren also played tárogató, a Hungarian reed instrument most people have likely heard in the hands of Peter Brötzmann, on one track from Cherry’s 1974 album Eternal Now.

Cherry and Rosengren worked together frequently when the trumpeter was living in Sweden. Movement Incorporated, a 2003 CD credited to Cherry, features live recordings from July 1967 with the saxophonist’s regular group with bassist Hultcrantz and drummer Leif Wennerström, fellow tenor saxophonist Tommy Koverhult, trumpeter Maffy Falay, alto saxophonist Bengt Nordstöm, trombonist Brian Trentham, and, on one track, Turkish percussionist Okay Temiz. The CD Brotherhood Suite collects more live recordings from 1968-74, including a 35-minute medley of Cherry’s “Brotherhood Suite I” and Abdullah Ibrahim’s “Bra Joe.” Live in Stockholm, from 2013, gathers even more music from 1968 and 1971. In 2021, yet another collection of previously unreleased collaborations between Cherry and Rosengren and many of the same players, plus others, was released as The Summer House Sessions.

In 1969, Rosengren was part of the large ensemble dubbed the Baden-Baden Free Jazz Orchestra, conducted by Lester Bowie on the half-hour title track from the album Gittin’ to Know Y’all. If you’re a fan of old-school free jazz blare à la John Coltrane’s Ascension or Alan Silva’s Seasons, this is a lesser-known title but one well worth digging up. (It’s on streaming services.) Back at home, he and some frequent cohorts — Fagerstedt, Hultcrantz, Wennerström and Koverhult — made the album Improvisationer, credited to Bernt Rosengren Med Flera (translation: “Bernt Rosengren With Several Others”), on which they juxtaposed versions of Miles Davis’s “Milestones,” Thelonious Monk’s “Evidence,” and Ornette Coleman’s “Congeniality” with some originals and two adaptations of Turkish songs, “Seuda Love” and “Arabamin Atlari,” featuring Falay.

Rosengren continued to do interesting work in the ’70s. There was a 1972 session, released in 2004 as Free Jam, on which he, Koverhult, Hultcrantz and Wennerström collaborated with South African trumpeter Mongezi Feza and Temiz. His 1974 double album Notes From Underground, though, is easily one of his best releases. It features his regular associates Falay, Koverhult, Hultcrantz, Wennerström, and Temiz, plus a bunch of other players, and musically it runs the gamut from traditional-sounding Turkish and Middle Eastern pieces to solid, bluesy hard bop tunes to the manic “Gluck” (stream it above), which sounds like Science Fiction/Broken Shadows-era Ornette Coleman, when he had Dewey Redman in the band and was absolutely ripping shit up.

In the last 15 years or so, Rosengren formed a new quartet with pianist Stefan Gustafson, bassist Hans Backenroth, and drummer Bengt Stark. They recorded four studio albums — 2008’s I’m Flying, 2012’s Plays Swedish Jazzcompositions, 2015’s Ballads, and 2017’s Songs — and in 2019 they released the simply titled Live, with guest saxophonist Christina von Bülow. I reviewed Songs for the NYC Jazz Record, and ordered copies of its three predecessors straight from the label afterward. They sent me the live album when it came out.

Rosengren’s late music was more straightforward and traditional than a lot of what had come before. He seemed to be relaxing into a kind of elder statesman role, fronting a group of players several decades younger than himself and interpreting well-chosen standards like “Delilah,” “Lush Life,” “Willow Weep for Me,” “Solar,” “The Things We Did Last Summer” (which he recorded on both Ballads and Songs), while also continuing to write new material. Seven of the 12 tracks on I’m Flying were his, as were three on Plays Swedish Jazzcompositions (others were by players and composers like Lars Gullin, Åke Johansson, and Nils Göran Sandström). His last two studio albums, Ballads and Songs, were all interpretations of classic tunes, but he put his own stamp on them, and his bandmates were superb accompanists, tackling everything from speedy hard bop to gentle ballads to swaying bossa nova grooves without ever seeming rote or disengaged.

On the live album, recorded in December 2017, two weeks before Rosengren’s 80th birthday, the addition of Christina von Bülow on alto sax gives the music a jolt. They open the set with a version of Hank Mobley’s “Workout,” which leads into a nearly 13-minute version of the 1937 tune “Gone With the Wind” (which has nothing to do with the novel or the movie). They also play the ultimate old-school tenor sax showcase, “Body and Soul,” but instead of letting Rosengren walk away with it, the two horns harmonize and trade phrases, having a true musical conversation spanning generations (Rosengren was born in 1937, von Bülow 1962). The album — and Bernt Rosengren’s recorded legacy — ends with a 10-minute version of “I Should Care,” featuring terrific solos from almost the entire band.

These five albums are all of a piece, and they’re all great. But they’re not on streaming services, so I recommend contacting the label directly to buy them, as I did. Bernt Rosengren was an adventurous but song-minded saxophonist, a Swedish equivalent to Dexter Gordon and Fred Anderson rolled into one. He deserves to be remembered by anyone who truly loves jazz as a language, for he spoke it with extraordinary fluency and grace.

Two more things, before I go:

• My latest jazz column is up now on Stereogum; it includes an interview with South African pianist Bokani Dyer, and reviews of new albums by Henry Threadgill, Milford Graves, Kassa Overall, Asher Gamedze, Artemis, and others. Here’s the link.

• I reviewed a bunch of classic jazz for Shfl last week, including albums and compilations by Count Basie, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie’s 1950s big band, and the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet. Check those out here.

That’s it for now. See you next week!

FYI, Apple Music does have those last studio albums, and the Live one with Christina von Bülow.

RIP. My introduction to this excellent musician was courtesy of Tomasz Stanko's Litania album, a tribute to Komeda