I am not a diehard Neil Young fan. His catalog is much too deep and expansive for me to spend my finite mortal lifespan wading through it all, but when he cranks up his electric guitar, he hits my pleasure center dead-on. Very few guitarists have a tone that suggests there are no amps in the world loud enough to truly do them justice, but Neil is up there with Tony Iommi, Keiji Haino, and Andy Hawkins (of Blind Idiot God). So his most brain-frying work — records like Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and Eldorado — will always have a place on my shelf.

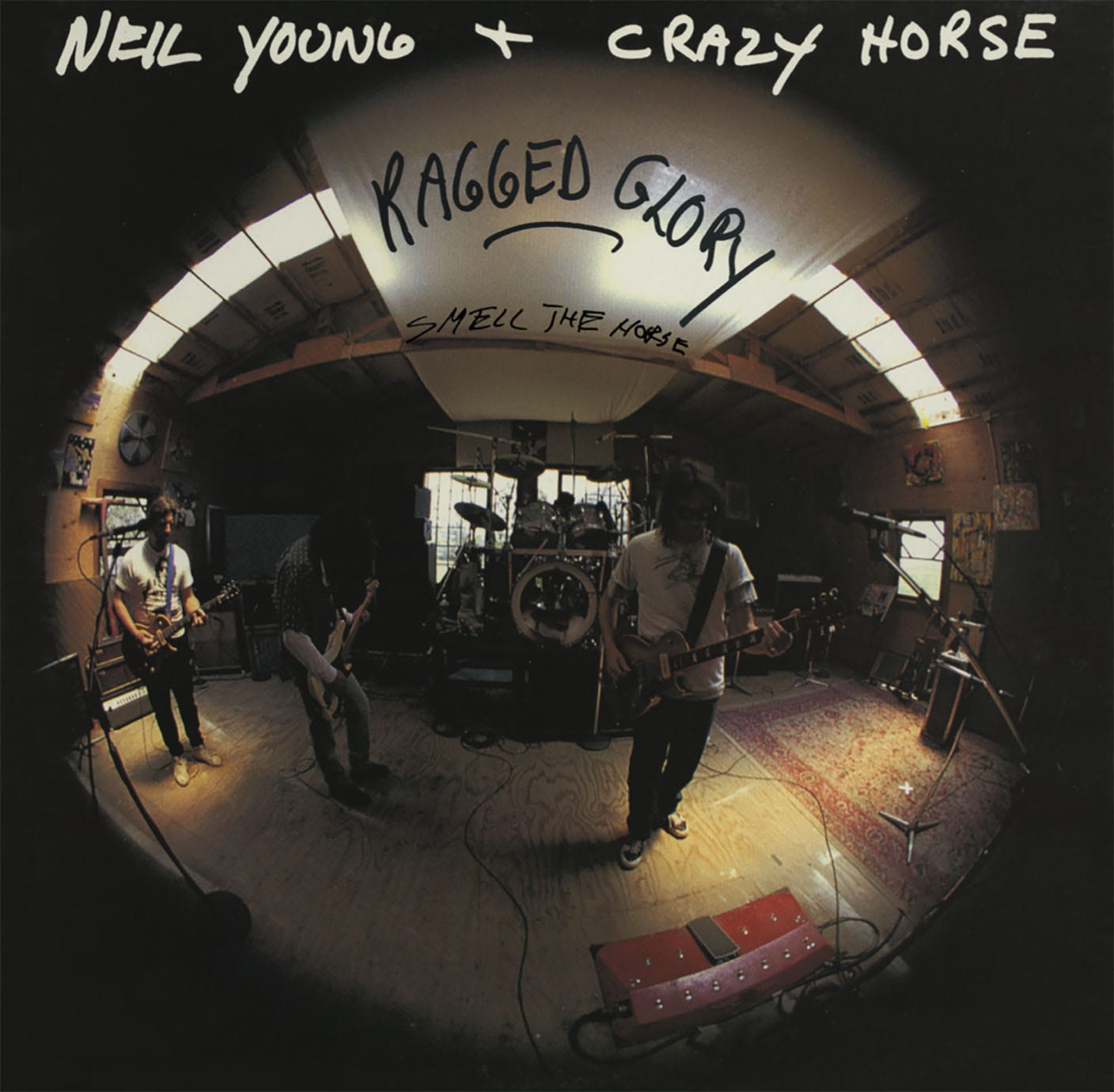

Ragged Glory, the 1990 album which has just been remastered, expanded and re-released, isn’t my favorite Neil record (that would be Eldorado), but it definitely lives up to its name, as it is both ragged and glorious. It has no acoustic songs, and only one ballad; it comes out of the gate with “Country Home,” built on an ear-piercing, distorted riff and a caveman backbeat, and grinds your face into the floor for seven straight minutes. Both the vocal harmonies and Young’s guitar soloing hover right on the edge of dissonance, somehow hanging onto tunefulness through force of will and momentum. The next song, “White Line,” has an almost polka rhythm, but you know what you get if you speed up polka? You get hardcore punk. “Fuckin’ Up” brings a tumbling rockslide beat and a riff so heavy it’s almost doom metal.

There are two long-ass songs on Ragged Glory, something that was unexpected at the time. “Love to Burn” and “Love and Only Love” both allow Young to take radically extended guitar solos, stretching the songs past the 10-minute mark. In an interview with Rolling Stone before the album was released, he explained, “I purposely wanted to play long instrumentals because I don’t hear any jamming on any other records. There’s nothing spontaneous going on on records these days, except in blues and funkier music. Rock ’n’ roll used to have all that. People aren’t reaching out in the instrumental passages and spontaneously letting them last as long as they can. I love to do that, but I can only really do it well with one band. I tried it a little on Freedom. But that style of music is better for me with Crazy Horse.”

The recording process was itself fascinating; rather than work on a single song until it was right (note: “right” and “perfect” are not the same thing, especially not in Neil Young world), the band “played a set of songs twice a day at Plywood Analog for a couple of weeks, then went back, listened, and chose best tracks after the two weeks were up. The Ragged Glory was picked from those tracks. The same tracks were never repeated in a recording set, played only once as set…and the band moved right on to the next song. No repeats. This approach took ‘analysis’ out of the game during the sessions, allowing the Horse to not think; thinking is deadly for the Horse.”

This is an approach I’ve only heard about from one other artist: the tenor saxophonist JD Allen, who pushes his band through tune after tune in the studio, with no pauses or retakes, until they’ve played an hour or so of music, as though they were on stage in a club. After one or two days of these “sets,” he takes all the music home and pulls out the best tracks. And if you’ve heard albums like Victory!, Graffiti, or Toys/Die Dreaming (the latter of which I was in the studio for — I wrote the liner notes), you know that the results can be extremely powerful.

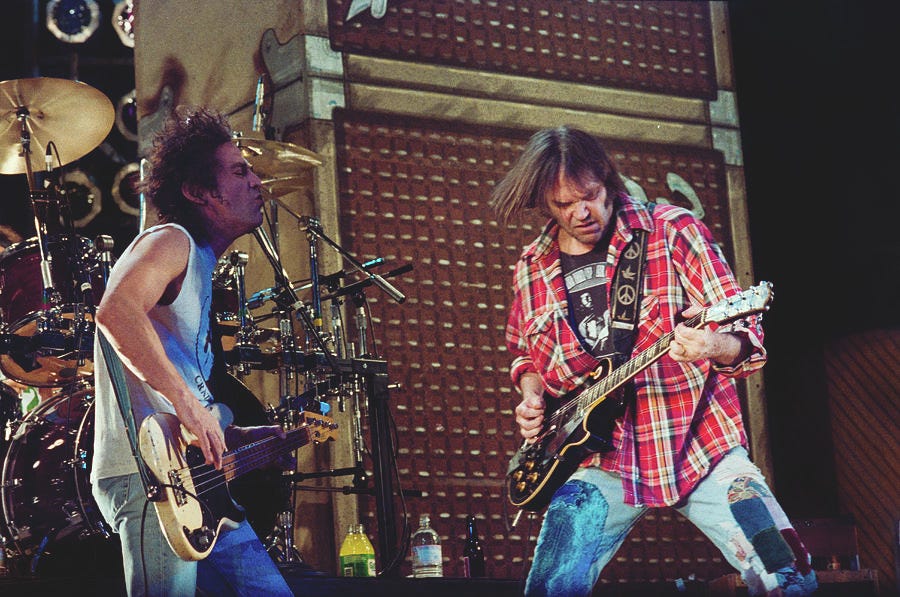

Young embarked on a tour in support of Ragged Glory in early 1991. I saw him on February 24, at what I always think of as the Meadowlands Arena (then called the Brendan Byrne Arena, and probably called something else now). This was the tour that Sonic Youth and Social Distortion opened, pissing off a lot of old hippies. I liked both bands — I had Social Distortion’s self-titled album, and had been listening to Sonic Youth for a few years already, owning cassettes of Confusion is Sex and Sister and actually splurging on the CD of Daydream Nation. I wasn’t too impressed by their live set, though, and it was the only time I ever saw them. Social Distortion were simply swallowed by the arena; when I saw them again a year or two later, in a mid-sized club (the Academy, in Manhattan) supporting Somewhere Between Heaven and Hell, they were great.

I went to the concert with my mom and my aunt, and my best friend Ken. My mom’s musical taste has always been pretty wide-ranging — she was born in 1949, so she liked the Beatles and Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones, but there were Buffy Sainte-Marie and Odetta albums in our house, too, and the West Side Story soundtrack, and when I was very young she used to listen to a DJ calling herself the Mellow Mother who played soft early ’70s singer-songwriter stuff. But when I was a teenager we bonded over Talking Heads and New Order, and she even liked Iggy Pop’s Blah-Blah-Blah (he had a pleasing baritone). The only music I wasn’t allowed to play in the house was AC/DC, because she hated Brian Johnson’s voice. My aunt, a few years younger, had gone to see the Allman Brothers Band at the Fillmore East multiple times. Ken and I went to a lot of shows together in the late ’80s and early ’90s: Keiji Haino, the Butthole Surfers, Revolting Cocks, King Sunny Ade, Thinking Fellers Union Local 282, Fishbone (with the 2 Live Crew as unannounced openers), GG Allin, the first Lollapalooza festival… Ken died suddenly in 2006, and I haven’t had a show-going buddy since.

Anyway, the concert was probably the loudest thing I’d ever heard to that point, or possibly since, and that includes seeing Merzbow and Borbetomagus at Tonic. It was astonishing, a wave of sound washing over the entire arena, drums like cannons and so much artfully sculpted feedback (Young would occasionally make a deliberately aggressive squalling noise, in humorous imitation of Sonic Youth) that it was like having your face shoved into a giant ball of barbed wire. In 1992, he released Weld, a double live CD from that tour that doesn’t have the impact of the show itself — what could? — but is still the loudest, heaviest thing in his catalog by far. If you put it on as loud as you can stand it, through good headphones, it’s pretty rockin’. He also released Arc, a 35-minute compilation of feedback, decontextualized vocal phrases, and guitar noise, which is sort of interesting to listen to…once.

A very different vision of this era of his music is offered on Way Down In The Rust Bucket, another 2CD live set released on February 26, 2021, almost exactly 30 years after the concert I saw. It was recorded in November 1990 at the Catalyst, a club in Santa Cruz, CA where the band was preparing for the upcoming arena tour. The two-and-a-half-hour set includes seven songs from Ragged Glory, and classics like “Cortez the Killer” and “Like a Hurricane” and “Cinnamon Girl,” but also dredges up less expected tracks like “Surfer Joe and Moe the Sleaze” and “T-Bone” from re•ac•tor, “Danger Bird” and “Don’t Cry No Tears” from Zuma, and “Homegrown” and “Bite the Bullet” from American Stars ’n’ Bars. The band is in a loose, jamming mood (six of its nineteen tracks pass the 10-minute mark), but playing at high volume — the result is Crazy Horse in stoner metal mode.

Anyway, back to Ragged Glory. It’s been reissued as part of one of his Official Release Series box sets, bundled with Freedom, Weld, and Arc. They’ve all been remastered, and the album sounds great: loud and splattery, with a really nice stereo mix that lets Young’s and Frank “Poncho” Sampedro’s guitars and Billy Talbot’s bass meander around each other as Ralph Molina keeps a rock-steady but ever so slightly swinging beat. And now there are four extra songs tacked on, roughly half an hour of music on a second disc. The first is “Interstate,” an acoustic ballad that would never have worked on the original album, but is nice here. It first showed up as a B-side of “Big Time,” from 1996’s Broken Arrow (itself a better-than-decent album). The next is the nearly eight-minute “Don’t Spook the Horse,” a sludgy country-doom absurdity that was released on a CD maxi-single (remember those?) as the B-side of the only single from Ragged Glory, “Mansion On the Hill.”

The last two songs are genuinely new, never before released. “Boxcar” is a three-minute psychedelic country song, an almost Hank Williams lyric and lonesome harmonica laid over a two-stepping beat, but the lead guitar is psychedelic in the manner of the spacier sections of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland. Again, it’s a nice song, but like “Interstate” it would not have fit in with the original Ragged Glory at all. The bonus disc ends with “Born to Run,” which is not a Bruce Springsteen cover (mercifully); instead, it’s a hard-driving guitar jam built on a herky-jerky riff somewhere between Devo and Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers that slows down for a dreamlike chorus, then surges back to life…and about three and a half minutes in, the “song” part is over for good and we’re headed down the highway for eight more minutes of unfettered, clawing-at-the-walls guitarrorism. This song rules, and should have replaced the turgid and goofy “Mother Earth (Natural Anthem)” on the original release.

Ragged Glory — Smell the Horse (the new title) is almost certainly going to be released separately, but for now, you can only get it as part of the latest Official Release Series box. Which I recommend you do. If you’ve never heard these records, they’re among Neil Young’s best — except for Arc, which is just something you can throw on to befuddle people or clear out a party. (The previous box in the ORS series was a much more mixed bag, including Hawks & Doves, re•ac•tor, and This Note’s for You, but it also has Eldorado, which had never before been available on CD in the US.)

That’s it for now; see you next week!