Book update! In case you haven’t heard, my latest book, In the Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor, is being published in July by Wolke Verlag. You can pre-order it from their website, and I recommend doing so, as there’s no US distribution at the moment. I’ll have a few copies later this summer, and will let you know when those are available for shipment within the US.

The Wire published an excerpt from the book, all about the making of the 1999 Dewey Redman/Cecil Taylor/Elvin Jones album Momentum Space, on their website. Click here to read it.

In other news: My latest Ugly Beauty column is up on Stereogum; it includes an interview with drummer Nasheet Waits and reviews of 10 great new releases, including an incredible archival live set by Charles Gayle, William Parker, and Milford Graves. Go read that.

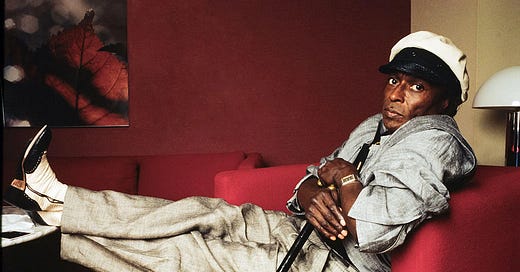

This summer marks the 40th anniversary of one of Miles Davis’s most under-appreciated albums. Decoy was released in 1984; I’m not certain of the exact date. It was a mix of studio recordings and highly edited live performances from a show at the previous year’s Montreal Jazz Festival (a concert which was later released almost in full). It’s probably better known now for its stark, ominous black-and-white cover photo by Gilles Larrain, an image that appeared on posters and on the cover of Davis’s autobiography, than for its music, which is kind of too bad.

Decoy is a short album — seven tracks in under 40 minutes — but to my ear it’s the most interesting release of his early comeback era. The Man With the Horn and Star People were tentative, padded records (the title track of the latter is a nearly 19-minute blues jam). But by 1983, Davis was out on the road with a tight young band, and when he went into the studio in June, August, and September of that year, he had definite ideas of what he wanted. It’s worth noting that this was his first album in about 30 years not to be produced by Teo Macero; Davis did it himself. His former keyboardist, Herbie Hancock, had a major hit that summer with the Bill Laswell-produced “Rockit,” and it’s easy to hear echoes of that track and Prince’s 1999 (the album and the song) in the music on Decoy.

The mix of live and programmed rhythms that keyboardist Robert Irving III, drummer Al Foster, and percussionist Mino Cinelu come up with, propelled by Darryl Jones’ thick, aggressive funk bass and adorned with subtle guitar from John Scofield, are High ’80s Pop, and recorded and mixed as such, crisp and clean at all times. The synth shimmers at the beginning of “Code M.D.” could have come off a Cyndi Lauper song. There was even a music video, directed by Max Headroom creators Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, for “Decoy.” Two fragments are available on YouTube, but I’d love to see the whole thing.

Branford Marsalis plays soprano sax on the three main studio tracks — the opening title piece, “Code M.D.”, and the 11-minute “That’s Right” — and gets more solo time than the leader, not unlike the way Dave Liebman was pushed front and center on 1972’s On The Corner, going off from the middle of the storm as Davis repeated a simple melody. Scofield, too, stretches out at length on “Code M.D.”; Davis himself isn’t heard until four minutes into the six-minute track, but his solo is full of powerful high notes, and shadowed by a second, muted trumpet line in the background. “Freaky Deaky” is an ominous keyboard-driven piece built around a “Theme From Peter Gunn”-ish bass line, with no horn at all. (Two outtake versions of this piece appeared in 2022 on That’s What Happened 1982-1985, the seventh volume in Sony’s Bootleg Series. They’re more conventional, and less interesting.)

Decoy is split into two neat halves. The cybernetic pop experiments are all on Side One; on Side Two, we hear Miles Davis the bandleader. The last studio track on the record is “That’s Right,” an 11-minute ballad that’s listed in the recording session files as “Slow Blues in 3.” Both Al Foster and Mino Cinelu are clearly audible, but there are no programmed drums, and Robert Irving III is playing simple synth chords beside Darryl Jones. Branford Marsalis and John Scofield come in playing a unison line/riff before the guitarist takes a gritty, biting solo, his best on the record. Davis was a superb blues player, something he demonstrated over and over, and “That’s Right” might be his best blues performance of the ’80s. It’s bracketed by two live tracks from the 1983 Montreal Jazz Festival, both of which are edited down, and notably feature no crowd noise at all. “What It Is” was originally six minutes but is just four and a half here, and “That’s What Happened” pulls three and a half minutes of uptempo funk-rock from a nearly 12-minute performance.

I think each side of Decoy has great merit. I find the at-times eerie synth-funk of the album’s first half more immediately intriguing, and would have welcomed an entire LP of that type of thing. The live tracks and “That’s Right” are very good, though, and give the listener an idea of what to expect from a Miles Davis concert of the era.

I wish there were more live recordings of Davis from the ’80s readily available. Other than Live Around the World, and the aforementioned volume of the Bootleg Series, there’s almost nothing. The big exception is the 20-CD 2002 box The Complete Miles Davis at Montreux, which compiles eleven concerts from between 1973 and 1991. There are two shows (afternoon and evening) from 1984, two from 1985, one each from 1986, 1988, 1989, 1990, and two from 1991, the first of which was released separately as Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux. That’s the one where Davis revisits the music he made with orchestral arranger Gil Evans in the late ’50s.

The 1984 live band consisted of Davis on trumpet and synth; Bob Berg on saxophones and flute; Robert Irving III on synths, John Scofield on guitar, Darryl Jones on bass, Al Foster on drums, and Steve Thornton on percussion. In Montreux, they played for over 90 minutes in the afternoon and nearly two hours at night, and they hit hard. Foster and Thornton laid down a face-slap of a beat to kick off “Speak/That’s What Happened,” with Scofield’s guitar sounding more like hard rock than jazz or funk and Jones popping his bass like Larry Graham. When it’s time for Berg to solo, Davis puts one finger on the keyboard and emits a constant piercing note the entire time. He shifts to a different piercing keyboard note when it’s Scofield’s turn in the spotlight. But when he’s soloing, he’s in amazing form, holding long notes on “Star People” (much better than the album version) and soaring higher than expected a lot.

Interestingly, almost nothing from Decoy made it into the live set in 1984; “Speak/That’s What Happened” kicks off both concerts, and “What It Is” is heard, too, but those were pieces they’d been performing since 1982. They also play “It Gets Better” and “Star On Cicely” from Star People; “Jean Pierre,” which first showed up on the live We Want Miles; and covers of Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” and D-Train’s “Something On Your Mind,” both of which Davis would record for the following year’s You’re Under Arrest. The only Decoy song heard at Montreux is “Code M.D.”, as the encore at the evening concert. The live version sounds great, a thick slab of churning ’80s funk.

I have thought for a long time that if more live recordings of Miles Davis’s final decade, especially from 1983-86, were released as stand-alones (instead of a giant, limited edition box that’s not even on streaming services), his music from that era would be appreciated in the way it merits. Oh, well.

That’s it for now. See you next week!

The first 80’s Miles lp I ever found, back when records cost next to nothing and were dusty and mouldy like old books. It’s remained my favourite from his comeback period precisely because of the short sharp electro-jazz-funk-noir excursions. I remember him appearing in Miami Vice and Decoy now sounds like an alternative score to that show 👌🏻

I saw him at the Hollywood Bowl in I think 1981 (poss. ‘82) and what stands out most clearly in my memory was how happy he seemed. He was sort of teasing the (by this point much-) younger musicians, acting a bit like a coach. There was more keyboard/synth noodling than there was memorable trumpet playing, but it was pretty early in his reemergence so pretty much everybody was just happy to have him back. (Besides, this was the era when you could see Weather Report live and count the number of seconds Wayne Shorter blew sax during any song on your fingers. Strange days.)

Miles thanked the audience at least a couple of times, and if I recall correctly, even cracked a couple of jokes. He looked like a man who was having fun.