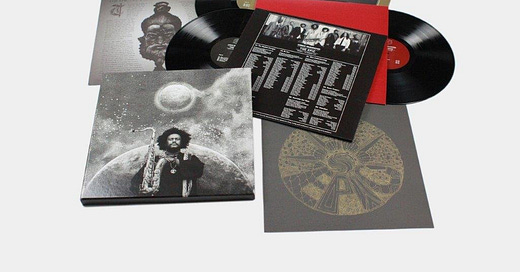

Kamasi Washington’s The Epic was released 10 years ago this month, on May 5, 2015. For those who don’t know, it’s a 3CD or 3LP set containing nearly three hours of music performed by a large jazz ensemble led by tenor saxophonist Washington, who also composed 14 of its 17 tracks. The core band is augmented by a nine-piece string section (five violins, two violas, two cellos) and a 12-person choir.

It wasn’t his debut, though it might as well have been — he’d self-released a 2CD live set and two studio (if a garage counts) albums with no distribution, and been part of a group called the Young Jazz Giants that made a single, little-noticed album for the Birdman label in 2004.

The Epic came out on Brainfeeder, a label founded by electronic musician Flying Lotus, rather than a typical jazz imprint, and Washington had connections to the L.A. hip-hop community to draw upon, having toured in Snoop Dogg’s band and contributed to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly. I knew very little of this when I reviewed The Epic for Jazziz. Here’s what I said then:

This 17-track, three-disc, three-hour collection lives up to its title. Grandiose in every respect, the music is performed by a 10-piece band, augmented by a full orchestra and a choir. Washington, who’s played on albums by Stanley Clarke, George Duke and Kenny Burrell, is one of a group of Los Angeles-based artists whose work blends jazz, electronic music, funk and hip-hop into an amorphous, swirling sound that’s miles deep and breathtakingly ambitious at times.

As a saxophonist, Washington is clearly a [Pharoah] Sanders acolyte; he’ll chew on a few notes like a mantra, then erupt in fierce shrieks. Pianist Cameron Graves, who gets the first solo of the set, comes across like a disciple of McCoy Tyner, but with a Don Pullen-ish fervor; behind him, the choir sings wordlessly. Trumpeter Igmar Thomas rips it up on “Miss Understanding”, blaring rippling, Freddie Hubbard-esque upper-register runs, and trombonist Ryan Porter is first out of the gate on “Leroy and Lanisha”.

Despite side trips into funk, reggae and R&B, The Epic is, at its core, a spiritual jazz album; had Impulse Records given Pharoah Sanders the budget for an orchestra and choir in 1972, he might have come up with something very much like this. Songs are built on throbbing, vamping bass lines, played on electric and acoustic instruments simultaneously, and they go on at great length — the first piece, “Change of the Guard”, runs more than 12 minutes, and that’s not unusual. When the music moves closer to R&B, it recalls the instrumentals that occasionally popped up on Earth, Wind & Fire albums. There are some surprises, too, like a reggae-fied version of the standard “Cherokee”, sung by Patrice Quinn (who’s featured on multiple tracks, not always to great effect; the lyrics get pretty hokey at times). And while there’s too much material here for the average, time-pressed listener to absorb in one shot, the playing is of high enough quality that eventually, serious jazz fans will (have to) make their way through all three discs, and they’ll be very happy they did.

Almost instantly upon release, the album was a breakout success. But in those first few months, it was still possible to see him as just a promising jazz artist. Yes, a 3CD set was a grandiose statement, but he was still staying within the bounds of the genre. A few months later, I attended Washington’s first New York headlining show, at the Blue Note. He was already playing much larger clubs across the country, but the Blue Note had name value. It wasn’t the Village Vanguard, but it was a sign that he was a serious artist, not some trendy flash in the pan. I wrote about the gig for The Wire:

Los Angeles-based tenor saxophonist Kamasi Washington has created one of 2015’s biggest jazz sensations with his three-CD debut, the aptly titled The Epic. His work with Kendrick Lamar and Flying Lotus gained him the attention of critics and listeners outside of the jazz cognoscenti, and as a result, it sold enough to make a full scale national tour economically viable.

Washington and his group moved from West to East, performing in sizable venues to large crowds. The first of four shows at New York’s Blue Note — a smaller, but much more prestigious, venue than usual — was packed with listeners in their late twenties and early thirties, whose conversations indicated they knew little about jazz beyond Washington’s music. His set provided an inviting entry point. He’s been touring with a six-piece ensemble: 17-year-old pianist Jamael Dean, trombonist Ryan Porter, vocalist Patrice Quinn, bassist Miles Mosley, and two drummers: Tony Austin and Ronald Bruner. They were joined for this show by Bruner’s brother Stephen, aka electric bassist Thundercat — who also appears on The Epic and was in town for the Afropunk festival — as well as trumpeter Igmar Thomas and alto saxophonist Terrace Martin.

The combination of acoustic and electric bass, and the double drummers, who combined forceful swing with driving rock and hip-hop backbeats, created a perfect platform for Washington, Porter and Dean. The leader’s blowing ran the gamut from voluble, high-speed hard bop lines to fierce, Pharoah Sanders-esque screams, combining his approaches into a sort of postmodern collage of five decades of jazz technique. Porter took only one solo the entire night, preferring to harmonize with Washington or Quinn. The teenage pianist displayed a heavy McCoy Tyner influence, when he could be heard; when the group was in full collective cry, he was buried in the mix. Mosley’s turn in the spotlight came with a jokey introduction from Washington, pointing out that it was “a regulation bass — no motors or buttons”; the resulting solo employed echo and electronic distortion to fantastically creative effect, building to a bowed passage of near-noise-rock intensity. Thundercat’s six-string bass guitar added a liquid sound reminiscent of 1970s fusion. Toward the end of the night, the drummers got theirs, erupting in a raucous percussion duel that would have brought the crowd to its feet had the tables not been too close together to permit any movement beyond rocking back and forth.

Three of the four pieces performed during the 75-minute set came from The Epic: “Change of the Guard”, “Re Run Home” (featuring Martin) and a soulful expansion of the jazz standard “Cherokee”, with Quinn delivering the lyrics and Thomas taking a New Orleans-flavored solo. Washington’s long-term goal is to bring all the members of his California crew into the spotlight, and towards the end of the set, they performed a tune of Porter’s called “Oscalypso” — the trombonist has an album of his own coming, as do several other musicians who played on The Epic. It was closer to the disco-funk fusion of the late 1970s than the spiritual jazz the saxophonist traffics in, but still showed the West Coast Get Down (their collective name) in a very favorable light.

I was instantly smitten. I’d enjoyed The Epic, but could have slipped it onto the shelf and moved on. The show made me a fan — I even bought a T-shirt. In the coming years, I interviewed Graves, Mosley, Porter, Martin, and Thundercat, but never Washington himself. They all had fascinating stories to tell about their friend and collaborator, and I started to get the impression of a whole scene I’d had no idea about that had been just doing the work for more than a decade before The Epic kicked open the door through which they all passed.

A year after playing the Blue Note, Washington was back in New York, but that time, he played the main room at Webster Hall, which held 1500 people — more than the 10 most famous jazz clubs in Manhattan put together. I wasn’t at that show, but I saw him again in June 2018, and that time he was playing a stadium — Forest Hills Stadium, to be exact, opening for the indie rock act Alt-J.

The sun was still out when the band took the stage — Washington, Porter, keyboardist Brandon Coleman, and vocalist/dancer Patrice Quinn up front, and bassist Mosley, Austin and Bruner in back. Up close and in the sunlight, I noticed he was wearing a football player’s mouth guard to play, removing it to address the audience between tunes. Mosley used pedals to crank his bass up to a skull-vibrating roar. Coleman soloed like a cross between McCoy Tyner and Keith Emerson, switching between piano and synthesizer at a moment’s notice, and the double drummers were positively apocalyptic.

The fact that Washington and crew hit hard certainly helped them get across to rock listeners. With only 40 minutes to play, they stacked the set with new and newish music, performing “Fists of Fury” and “Street Fighter Mas” from Heaven And Earth, and “Truth” from the previous year’s Harmony Of Difference EP. And the audience, which was again overwhelmingly young, at least down on the ground where I was, was into it. They were dancing, cheering, shouting, and occasionally singing along with Quinn’s often-wordless vocals.

Washington has continued to climb the mountain of commercial success. Heaven And Earth was announced as a double CD and turned out to be another triple, with a secret third disc, The Choice, tucked inside the package in a way that required a razor blade to get it out. He composed the soundtrack to a Netflix documentary about Michelle Obama; put out another double CD, Fearless Movement, in 2024; and most recently scored the HBO anime Lazarus.

So let’s address the question in the title of this post: Why him? Because not everyone has been thrilled by his ascent. People have said that he’s not a great player, that his compositions are samey and his albums too long, and generally acted like his success was unearned and the product of hype. All of which is bullshit. You don’t get hired to play in George Duke’s band, or Stanley Clarke’s band, or the Gerald Wilson Orchestra, if you can’t play.

Was there a certain amount of image-shaping going on between the recording of The Epic, in 2011, and its release four years later? Absolutely. On his earlier self-released CDs, Washington had shorter hair and wore fedoras and church suits. By 2015, he was the wild-haired, dashiki-ed, ring- and amulet-bedecked spiritual jazz messiah figure seen on the album cover. He looked the part. And since then, his look has continued to evolve in a very marketable way. But as Branford Marsalis once told me, there’s a reason people say they’re going to see a band play. Washington is a showman, who has created a larger-than-life persona (literally so; he’s not as tall as Shabaka Hutchings, but he’s a solid six feet) and inhabited it to the hilt.

There’s precedent for his kind of crossover success, too. At the height of the hippie era, saxophonist Charles Lloyd’s quartet, which featured a young Keith Jarrett on piano, played the Fillmore in San Francisco, and their album Forest Flower — the second of eight they’d release between 1966 and 1968 — went platinum. In the late 1990s, David S. Ware’s quartet, with Matthew Shipp on piano and William Parker on bass and a series of drummers, signed to Columbia (Marsalis was their A&R man) and once opened for Sonic Youth at Irving Plaza. Worth noting: Their second and final release for Columbia, Surrendered, included a version of Lloyd’s “Sweet Georgia Bright.” Ware didn’t go platinum, but he did get reviewed in Rolling Stone. Neither Lloyd nor Ware played music that conceded anything to rock audiences, and yet they connected with the people who heard them, especially onstage. (Seven of Lloyd’s eight Sixties albums were recorded live.)

I finally got to interview Kamasi Washington in 2024, for Stereogum. And I asked him about his ascent, about being able to return to a city and play a bigger venue than he’d played the year before, and an even bigger venue the year after that, about being one of the most successful jazz musicians of his generation.

“Yeah, it felt surreal,” he said. “I mean, I’ve been making music my whole life, and I played a lot of big stages with other artists, and I always had my own music that I believed in, but you just never know if it’s ever going to basically see the light of day. You just never know if that opportunity will ever come to you. So for me, it was like something that I’d believed in for years and years and years kind of coming to fruition, you know. And so as the stages got bigger and the crowds got bigger and the reality that, like, what we always said — that this music that we were making, it wasn’t music that that could only be listened to by people who were quote-unquote jazz fans. It was a universal music that had a place everywhere, and it just felt that way. And it felt more and more that way as we traveled and got to play and, you know, it felt good. It felt like we were speaking to the people and giving them something that they were looking for, [and] at the same time, something that was truly in our hearts.”

Kamasi Washington’s music is popular because it’s populist. Like Charles Lloyd in the Sixties, like Grover Washington, Jr. in the Seventies, he writes compositions with big, memorable hooks, plays them like he’s enjoying himself, lays down a big beat, and never lets a solo become a 20-minute technical exercise.

The version of “Cherokee” on The Epic is a perfect example. Ever since Charlie Parker, saxophonists have used that tune like a solitary teenage boy uses a gym sock. Not Washington. He sets it to a reggae beat, and lets Patrice Quinn sing the whole song.

There are passages of serious instrumental heat on all of his albums, and examples of genuinely knotty and challenging compositional math. And those strings and choirs are arranged with real care. But the hardcore jazz stuff is balanced by covers of Eighties R&B tunes, kung fu movie themes, and Debussy’s Clair de Lune, and many of his pieces are built around deceptively simple, soaring vamps that stick in your head the way a head from a 1960s Lee Morgan or Hank Mobley album might.

I firmly believe in the idea of jazz as music that normal people can listen to for entertainment, and it’s clear that Kamasi Washington believes in that idea, too. The Epic was designed to meet listeners more than halfway. Its length offers a challenge, but its individual pieces extend a hand and draw you in. And it’s impossible to argue that it’s been anything but good for jazz as a whole. Artists like Shabaka Hutchings, Chief Adjuah (fka Christian Scott), and Nubya Garcia, to name just a few, have traveled in Washington’s wake, reaching hip-hop, R&B, dance music, and indie rock fans with honest music made on their own terms. Might their careers have taken off without The Epic? Sure, but jazz needed an injection of star power in 2015, and Kamasi Washington provided it.

That’s it for now. See you on Friday, when I will be announcing two incredible new releases from Burning Ambulance Music!

Fully agree, Phil. I'd venture that there's a subtle but unmistakable rhythmic reason that younger audiences are connecting with his music. Even in a standard like 'Cherokee,' I don't hear swing eighths underlying his playing – they seem more like Hip-hop eighths, if that makes any sense.

Thank you for articulating all of this, Phil. When I saw the title of the post I thought for sure you were going to be a negative Nancy about Kamasi's ascent. It turns out you're too observant and openminded to take that tack.