Happy New Year! I spent this past weekend tallying, and it seems like I had an extraordinarily busy 2022. I wrote:

• 15 features (for Bandcamp Daily, DownBeat, Stereogum, We Jazz and The Wire)

• 10 essay-length “guides” for Shfl

• 708 album reviews (for DownBeat, the New York City Jazz Record, Shfl, Stereogum, and The Wire)

That’s not counting about 35 pieces I wrote for this newsletter or for BA proper. I also produced nine episodes of the BA podcast (which is on hiatus for the moment, btw), released two albums on Burning Ambulance Music, and did a few other things (including getting my first byline in the New York Times, as part of a critical roundup on Ornette Coleman). I doubt I’ll match that pace this year, but we’ll see.

As you know if you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, I’m currently working on a book, In the Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor, which will be published by Wolke Verlag sometime in 2024. (You can join my Patreon to support this project and read exclusive excerpts from each chapter before anyone else. An excerpt from Chapter 4, which deals with the years 1960-63, just went up.)

When I interviewed Taylor in 2016, on the occasion of the Whitney Museum exhibition devoted to his life and work, the most contentious part of the two days we spent together came when we discussed ancestry and the question of whether to cling to one’s roots or cut them off and stride forward. I told him the story of my earliest known ancestor, who came to the US from Sweden in the 1800s and upon arrival changed his name from Jonsson to Freeman, symbolically cutting ties to his former country and to his family. To me, this has always been an inspirational story of one man’s determination to be himself. Taylor was horrified.

“How can you cut off your roots? Please tell me that. Why would you want to? Who are you without your beginnings?” he asked. “Have you ever heard ‘Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue’? Why would anyone ever want to shake that off? Or ‘Bensonality’? Or what Ella [Fitzgerald] did on ‘Cotton Tail’, which was with Ben Webster? Or ‘Main Stem’? Or ‘Johnny Come Lately’? That’s a heritage that continues onward.”

And yeah, when talking about art, of course he’s right. There is no future without acknowledgement of the past. (N.B., that doesn’t mean I’ve softened my position on musicians who mostly, or only, play “standards.” Be as inspired as you want by the music that came before you, but the only way to be a jazz artist of any significance, in my opinion, is to write music of your own.) I was speaking more of individualism, of cutting oneself free of a possibly toxic past in order to create better options for the future.

But jazz, perhaps more than any other form of music, is in constant communication with the past. Sometimes just the music’s past, but other times a broader, deeper past, something more ancestral, something that pumps in the musicians’ very blood. I’ve recently heard three fascinating albums that take different approaches to this challenge, or dilemma, or whatever you want to call it.

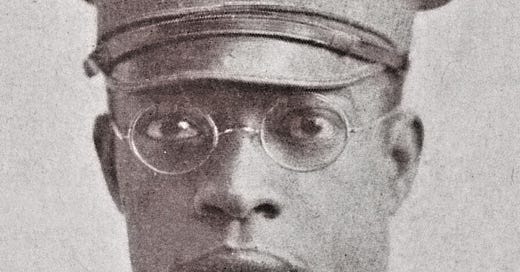

Konjur Collective is a trio from Baltimore, Maryland — Show Azar on synthesizer, Jamal Moore on alto sax, trombone, electronics, and percussion, and Bashi Rose on drums. Their debut album, Blood In My Eye (A Soul Insurgent Guide) came out digitally and as a double LP in October on a new label, cow: Music, with help from Astral Spirits. It’s a pounding, intensely rhythmic blast of energy, recorded hot and raw with everything bleeding together and mixed so it’s like someone thumping you in the chest as he shouts at you, but with love. It opens with a 21-minute track, “George Jackson,” named for the revolutionary who wrote Blood In My Eye and Soledad Brother from prison; another track is named for Jackson’s younger brother Jonathan. Other pieces are called “Ancestral Dialectic” and “Revolution Should Be Love Inspired,” deepening the album’s message; the latter breaks down from mantra-like horn-and-synth jamming to a stunningly blown-out drum solo.

In the liner notes, cow: Music founder Gabriel Vanlandingham-Dunn writes, “Baltimore, Maryland has always been a hotbed of musical activity. Legends such as Chick Webb, Billie Holiday, Stanley Cowell, Lafayette Gilchrist, Vattel Cherry, and Gary Bartz have all called the city home at some point in time.” This is an album that is in direct conversation with Baltimore music, not just the jazz figures named — though I can definitely imagine Gary Bartz and Lafayette Gilchrist (whose band combines jazz and go-go into something that will shift your organs around inside your body) getting into this — but present-day avant-hip-hop acts like Abdu Ali, Infinity Knives, and JPEGMAFIA. It’s got the fire and fury of Albert Ayler and Arthur Doyle, mixed with the electronic noise of Sun Ra at his out-est, but it’s got a punk energy that challenges the listener to strap in and hang on.

I’ve talked cow: Music into giving away 10 Bandcamp download codes for copies of Blood In My Eye; if you want one, email me and I’ll have them hook you up.

Pianist Nduduzo Makhathini is engaged in a long-term project wherein present-day South African jazz, in which he is possibly the crucial figure while remaining at the center of a vast, creatively fertile community, is linked to the country’s broader musical history and raised up as a tool for expanding post-colonial, post-apartheid cultural consciousness. His music combines influences from America — you can hear echoes of McCoy Tyner, Randy Weston and even Matthew Shipp in his playing — with those from South Africa like Bheki Mseleku and saxophonists Zim Ngqawana and Winston Mankunku Ngozi. He’s just released Abasemkhathini Vol. I, a collaboration with poet, singer, and historian Mbuso Khoza and alto saxophonist Justin Bellairs. It’s a live recording on which they perform songs from Makhathini’s albums, one from trumpeter Ndabo Zulu’s Queen Nandi: The African Symphony (which I wrote about here in 2020), and some interpretations of songs by Princess Magogo, a crucial figure in South African music at the beginning of the 20th century. And in between songs, Makhathini and Mbuzo discourse on issues of identity and how they impact culture.

“Jazz was born as a result of displacement and looking at, how do I define myself in this foreign land?” Makhathini says at one point. “And home is a utopian idea that you try to pull together. You’re grouped…where you can’t really speak the same language. And you start to dance, and dancing is banned. You start to sing, and singing is banned. Jazz becomes one element of an echo…from a place that is supposed to be a place of origin but that has become a foreign place.”

The lyrics that Makhathini and Khoza sing are mostly in isiZulu, a language I don’t speak, but the discussions in between are in English. And anyway, the music — just piano, saxophone, and vocals — is fantastic. Despite there being no percussion instrument, it’s intensely rhythmic, pulsing with life. There’s a fantastic version of “Unonkanyamba,” from Makhathini’s latest Blue Note album In the Spirit of Ntu, and the interpretations of songs written by Princess Magogo (“Onomusa Phezukonke,” “Intabeshipheli,” “Yini Bafowethu?”) are amazing, too. But the centerpiece of the performance is Khoza’s “Zul’eLiphezulu,” a stunning, nearly 10-minute fusion of blues and amahubo (Zulu praise singing) that’s both virtuosic and raw. And Bellairs’ alto sax, soulful and powerful, is a crucial third voice.

When Makhathini and Khoza harmonize, improvising these songs together, it’s a sound that expresses many things all at once: musical brilliance, shared cultural history, and perhaps most importantly of all, a palpable fraternal love and mutual admiration. And the enthusiastic response from the audience adds one more element. This is much more than just a live jazz recording; it’s a ritual, a lecture, a celebration, and an act of coming together, performers and audience and the broader world all becoming one. Whether you’re already deep into South African jazz, or new to it, this is a great starting point.

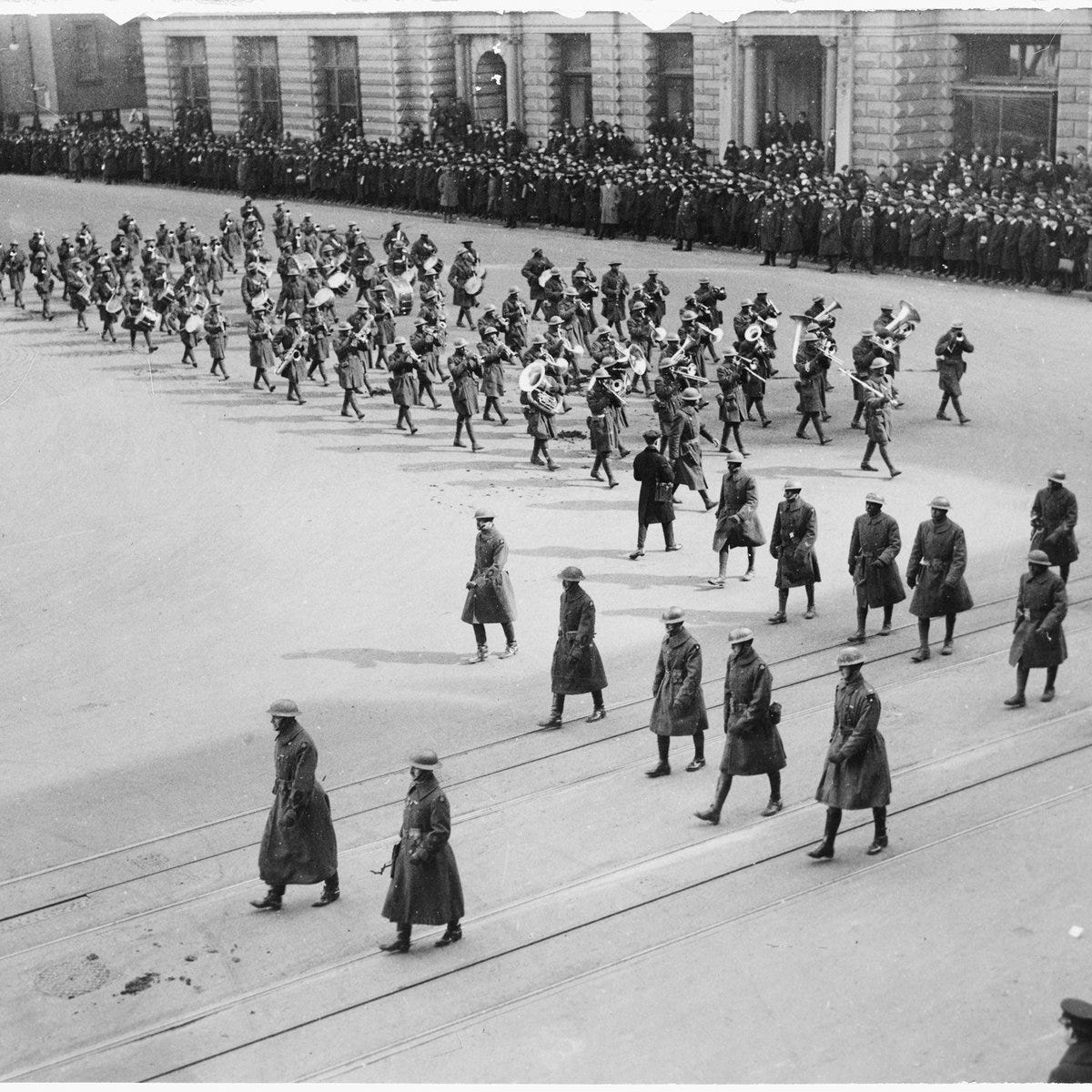

Pianist Jason Moran released From the Dancehall to the Battlefield on New Year’s Day. It’s a tribute to the life and music of James Reese Europe, a key figure in the development of jazz (before it was called that) and of Black music in America generally. Europe started out as a violinist, studying under Frederick Douglass’s grandson Joseph Douglass; he later came to New York and formed the Clef Club, a Black musicians’ union and orchestra that put on a concert at Carnegie Hall in 1912 that featured 125 Black musicians, playing exclusively music by Black composers. Europe achieved his greatest fame during and immediately after World War I; he fought as part of the 369th Infantry Regiment, known as the Harlem Hell Fighters, and led the regimental band, performing all over France and recording a series of 78s before returning home.

From the Dancehall… features a relatively small ensemble (Tarus Mateen is on bass and Nasheet Waits on drums, with David Adewumi on trumpet, Reginald Cyntje and Chris Bates on trombones, Logan Richardson on alto sax, Brian Settles on tenor sax, Darryl Harper on clarinet, and crucially, José Davila on tuba). The music includes versions of Europe’s “Ballin’ the Jack,” “Clef Club March,” “Castle House Rag,” and “All of No Man’s Land is Ours,” W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues,” “St. Louis Blues,” and “Hesitating Blues,” and some new Moran compositions, but what’s fascinating is the way the ensemble blends old and new, combining “Ballin’ the Jack” with Geri Allen’s “Feed the Fire” and connecting the traditional spiritual “Flee as a Bird to Your Mountain” with Albert Ayler’s “Ghosts.” Europe’s music isn’t jazz, exactly — it’s some head-spinning combination of ragtime and highly syncopated military band music — but it’s a crucial element of Black American cultural history, and Moran and his band have made an album (which is just one element of a multimedia show that he’ll be taking on the road in 2023) that’s a fucking blast to listen to. And if you’re interested afterward, Europe’s own recordings are available on streaming services and they’re pretty amazing, too.

I interviewed Moran about this project, and much more, on Monday; that’ll be part of my Stereogum column later this month. In the meantime, check out From the Dancehall to the Battlefield.

That’s it for now; see you next week!

Thanks for the tip on the new Makhathini and Moran records!

Thanks for the link to your Shfl