Before we begin, a major announcement: Burning Ambulance Music has partnered with the legendary UK avant-garde (with apologies to Ted Gioia) jazz label Leo Records to bring their catalog to Bandcamp for the first time. Because of the sheer volume of music they’ve released over the last 45 years, we’ll be doing it in waves. The first wave will include titles by Anthony Braxton, Sun Ra, Amina Claudine Myers, Marilyn Crispell, Cecil Taylor, Evan Parker, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Joe and Mat Maneri, Joe Morris, Joëlle Léandre and others; the second wave will focus on the work of Ivo Perelman (who has close to 70 releases on Leo); the third wave will explore Russian avant-garde jazz by the Ganelin Trio, Sergey Kuryokhin, Sainkho Namtchylak, Simon Nabatov and others; and the fourth wave will deal with the rest. We’ll be putting out 20 titles a month, with the first batch of titles by Braxton, Ra, Crispell and Myers arriving on Friday, September 6. So bookmark leorecords.bandcamp.com and get ready!

Book update! I am informed that there will be a review of In the Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor in the upcoming issue of Jazznytt, out in September. I look forward to practicing my Norwegian as I try to decipher it. I believe the book will also be covered in We Jazz, an excellent English-language magazine published in Finland. You should be able to order that from wejazzrecords.bandcamp.com sometime next month; I’ll post a link when it’s up. In the meantime, the book itself is available from Amazon and/or direct from the publisher.

“Popular music is popular because a lot of people like it.” — Irving Berlin (possibly apocryphal)

“Pop…never dies because it’s merely the top of the charts, whatever that may be.” — Joe Carducci, Rock and the Pop Narcotic

“I sing all kinds.” — Elvis Presley

Every time I start thinking about Elvis Presley, I wonder if anyone else still does. His cultural stature seems quite diminished in the 21st century, and not just because of losers who only seem to bring him up so they can talk your ear off about Big Mama Thornton. (Yes, she recorded a version of “Hound Dog” before he did. Who cares? It wasn’t her song either, and the writers, Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, got paid both times.) Yes, there was a movie about him the other year. I reviewed it, and when discussing the music, I stand by what I said:

Though Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bo Diddley, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, and plenty of others recorded (and wrote) incredible songs, Elvis Presley was a genius at synthesis. He brought together elements of country, blues, gospel, and R&B with a reckless lack of consideration for what “belonged” with what, and the sly joy audible in every word made it seem like he was jovially punching you in the shoulder, and grabbing your ass at the same time. The other great performers of the early rock ’n’ roll era could mostly do one incredible thing. Little Richard whooped so loudly it’ll still make you think your headphones are going to fly off your head; Chuck Berry was one of the sharpest, wittiest lyrical observers America has ever produced, and the first punk rock guitar player; Bo Diddley was a bizarre and hilarious primitivist genius; Jerry Lee Lewis was a creature of pure lustful, rageful id; but Elvis was simultaneously a chameleon (as he famously said, “I sing all kinds”) and utterly, purely himself.

But I don’t think Elvis’s music has endured in the way it should. Primarily because the culture industry doesn’t seem as interested in shoving it down people’s throats as they do the music of the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. Is that because Elvis has been dead for almost 50 years, while a few members of those bands are still technically alive? Maybe. But it’s still too bad, because his best records are some of the best music ever made.

In recent years, there have been attempts to “rehabilitate” or somehow re-present Elvis’s music. Some of these sets, like 2013’s Elvis at Stax, 2020’s From Elvis in Nashville or 2012’s live Prince From Another Planet (documenting two 1972 shows at New York’s Madison Square Garden) are fantastic. Others, like 2015’s If I Can Dream, are atrocious. Here’s the promo copy for that latter thing:

An exciting revisit of Elvis’ work, If I Can Dream focuses on the iconic artist’s unmistakable voice, emphasizing the pure power of The King of Rock and Roll. Recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London with acclaimed producers Don Reedman and Nick Patrick, the 14-track album features Elvis’ most dramatic original performances augmented with lush new arrangements by The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. “This would be a dream come true for Elvis,” Priscilla Presley says of the project. “He would have loved to play with such a prestigious symphony orchestra. The music... The force that you feel with his voice and the orchestra is exactly what he would have done.” Don Reedman also commented, “Abbey Road Studios and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra are as good as it gets and Elvis deserves as good as it gets.” The album features a scintillating duet with best-selling jazz-pop singer Michael Bublé on “Fever.” The album also includes additional contributions by Rock and Roll Hall of Fame guitarist Duane Eddy adding his signature sound to “An American Trilogy” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” and Italian operatic pop trio Il Volo lending their outstanding vocals to “It’s Now or Never.” As arranger Nick Patrick said, “This is the record he would have loved to make.” If I Can Dream also highlights Elvis Presley’s diverse musical tastes and appreciation for great vocalists spanning a variety of genres from standards to opera.

What a nightmare that is to even contemplate. Michael fucking Bublé. Jesus.

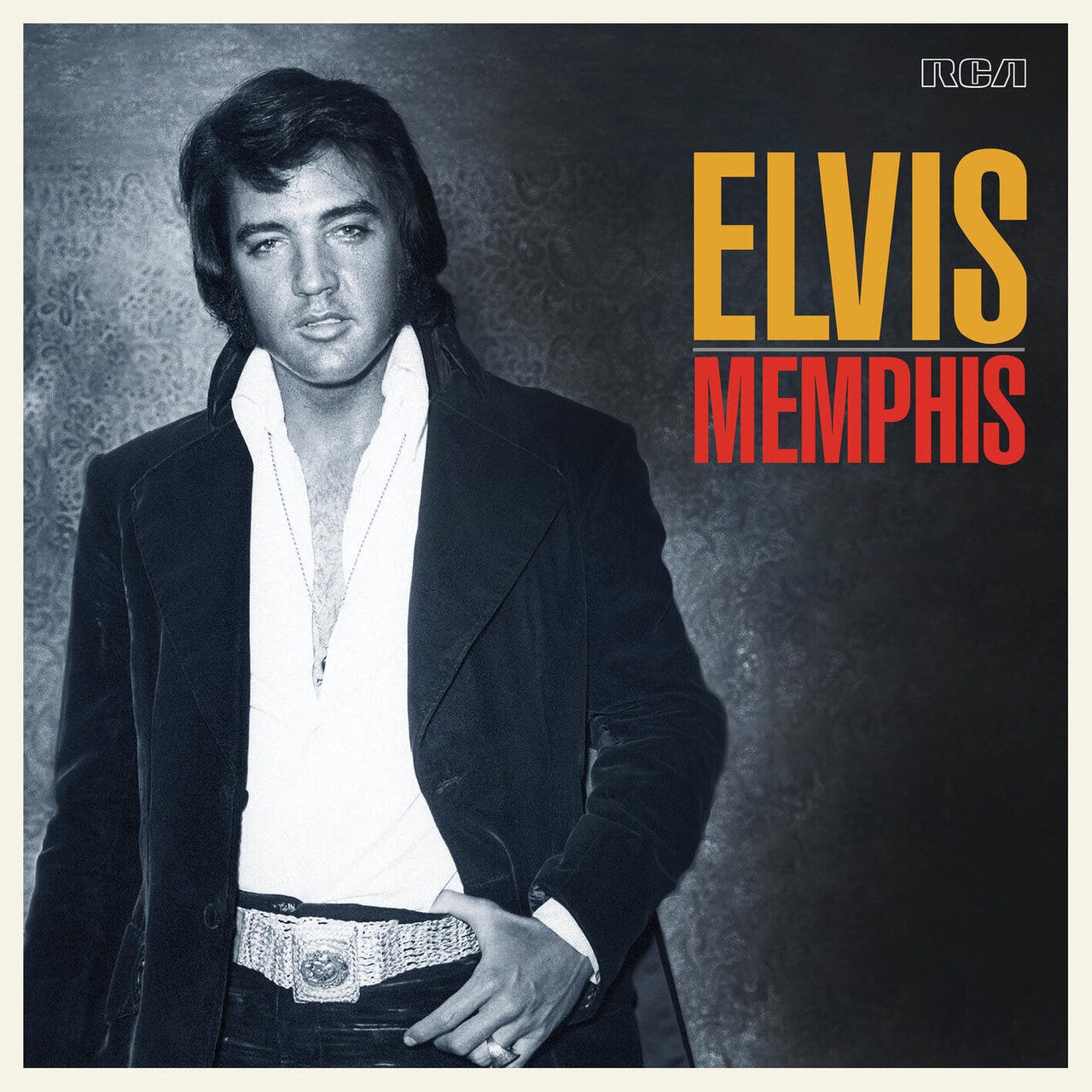

MEMPHIS is a new 5CD set that gathers the highlights of the recording sessions Presley did in his more-or-less hometown. (He was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, but he and his parents moved to Memphis when he was 13, and that’s where his former home, Graceland, is.) The first disc is pulled from the “Sun Sessions,” the 1954 and 1955 recordings, backed by guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black, that launched his career and got him signed to RCA. Listening to these bare-bones, two-track recordings now, it’s incredible to realize that this jump-out-of-your-pants music was made with just two guitars (one electric, one acoustic) and an upright bass.

It’s a surprisingly varied collection of material. There are fast, ultra-high-energy tracks like “That’s All Right”, “Good Rockin’ Tonight”, “Baby, Let’s Play House”, and “Mystery Train”, but also tender country ballads like “I Forgot to Remember to Forget”, “I Love You Because”, “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin”, and “I’ll Never Let You Go (Little Darlin’)”, and sui generis tracks like the absurd “Milkcow Blues Boogie” and the eerie “Blue Moon”.

Most of these songs were not big hits (it was hard to get radio play at first, because they weren’t country enough for country stations and too hillbilly for R&B stations), and they’re 70 years old now, so you may not have heard them. Trust me, they’re stunning. Elvis had a try-anything spirit in these early days that manifested not just in his choice of material but his approach to it. He sings some songs in a naïve upper register, others in a low growl. He doesn’t just match his bandmates’ energy; he’s a conductor for it.

Unfortunately, MEMPHIS goes awry on its next two discs. After becoming a huge star in the second half of the 1950s, Elvis joined the Army for several years, and when he came back the industry that had made him seemed hell-bent on destroying him via more than a decade of abysmal movies and worthless soundtrack dross. Finally, in December 1968, his “comeback” TV special allowed him to break his chains and re-introduce himself to the world. Almost as soon as it aired, Elvis went into American Sound Studios in January and February 1969 to record From Elvis in Memphis, which came out that June. It resurrected his career, turning him into an album artist at a stroke.

Unlike many of his earlier non-soundtrack releases, which threw together a couple of rock ’n’ roll numbers, a couple of soppy ballads, and a take on whatever was popular at the moment (a 1961 album was literally called Something For Everybody), on From Elvis in Memphis producer Chips Moman and his house band, informally known as the Memphis Boys, built taut country-soul arrangements that served the songs rather than making craven attempts to chart, and Presley’s vocals were delivered with more passion and craft than he’d shown in years.

For about a half dozen years after that, Elvis Presley made the best music of his career. Sometimes he headed to Nashville and went in more of a country direction; sometimes he came back to Memphis and explored funk and soul, blending those sounds with classic rock ’n’ roll, blues, and gospel, as well as the sweeping ballads he loved. The resulting albums — Elvis; Elvis Now; Elvis Today; the half-live, half-studio That’s the Way It Is; Elvis Country; the gospel album He Touched Me; and particularly the 1973-75 trilogy of Promised Land, Raised On Rock and Good Times — are a brilliant fusion of all the elements that made his music some of the most glorious art of the 20th century.

He also became a hard-working live act, undertaking years-long residencies in Las Vegas but also traveling across the US to play arenas, delivering high-energy shows that mixed old and new material, all played by an insanely talented band featuring lead guitarist James Burton and drummer Ronnie Tutt.

A compilation that just gathered the best songs Elvis Presley recorded in Memphis studios would have been fantastic. Unfortunately, MEMPHIS performs the crudest sort of vandalism on the material. Engineer Matt Ross-Spang, who’s worked on numerous recent Presley projects, has taken the tapes and removed the overdubbed strings, horns, and sometimes even the backing vocals that were used on the original albums and singles. So what you hear, for the most part, is the raw takes cut by Elvis and the core studio band — guitar, bass, drums, and piano and/or organ. And this is a huge mistake.

This approach worked on From Elvis in Nashville, because those tracks were the product of a five-day June 1970 session where Presley and the musicians were all in the studio at the same time, cutting country-rock numbers and folky singer-songwriter tunes live, and the strings really were extraneous. But when he was working at American in 1969 and at Stax in 1973, there was a core band, but additional instruments were always part of the plan. So stripping away the stuff that was added later doesn’t make these songs stronger. In fact, it weakens them.

For example, the austere strings and hushed female backing vocals on “In the Ghetto,” the single from From Elvis in Memphis that shocked many listeners (Elvis, doing something that was halfway to a protest song?) really added to the song. Another song from that album, “Long Black Limousine,” truly suffers from the absence of a female chorus that shadowed and accented Elvis’s lead vocal, and a beautiful trumpet solo. It’s still a good song with just his voice, piano, organ, bass and drums, but it used to be a great one. The From Elvis in Memphis album opener, “Wearin’ That Loved On Look,” depends for half its fun on the interaction between Elvis and the backing singers, who are missing here. He sang the lead knowing they’d be there later (there’s a terrific gospel breakdown before the final verse), and he just sounds weird left on his own. And don’t get me started on what they’ve done to “Suspicious Minds,” once a glorious epic, now a glorified demo.

Compare and contrast the two versions of “Long Black Limousine” for yourself. Here’s the album version:

And here’s the MEMPHIS version:

I know, right?

Elvis’s hard-charging blend of country and soul, perfected between 1969 and 1974, required a panoramic canvas for its impact. This was true in the studio as well as in concert — and this set also includes a full live concert from 1974, but that’s available separately. He wasn’t the Elvis of the 1950s, singing in front of just guitar and upright bass (and later, an ultra-minimal drum kit). He was the Big Show. These “unadorned” recordings featuring just guitar, bass, drums and organ allow you to focus on his voice — and yeah, he was an incredible singer, able to toss a wild flourish into the middle of a line, then get right back on track. And you also get to listen more closely to the core band, which can be great. Nobody ever overplays; they just lay down supple, solid blues and country grooves behind the Man. But nothing here is genuinely improved for having been stripped down.

If I was assigning homework to someone who wanted to understand the greatness of Elvis Presley, I would give them the Sun Sessions, From Elvis in Memphis, the Elvis at Stax compilation, From Elvis in Nashville, and a live set: either Prince From Another Planet or the 1972 concert film Elvis On Tour. But MEMPHIS is, frankly, a bummer, and I don’t think I’d ever recommend it to anyone.

That’s it for now. See you next week!

Only because you mention Irving Berlin and some other pop songwriters, as well as the ups and downs of reception history, a basically unrelated anecdote I just learned about Harry Warren. Warren had more hit #1 songs than anybody, but Irving Berlin always remained America's Songwriter. As a result, Warren became incredibly jealous. In the 1950s, as his sort of Tin Pan Alley songwriter vanished into history (replaced by Elvis etc.), he'd tell his friends, “In WWII they bombed the wrong Berlin.”

Dead-on. I took a brief listen on streaming and knew this wasn't one to own, even if I love most of this material. They've been doing "undubbed" mixes of the 1969 American stuff since the 1999 "Suspicious Mind" comp, the FTD releases etc. No-one should be introduced to this material this way, but I fear that's what will happen.