You’ll never hear everything. Once you recognize that, you can allow yourself to take far greater pleasure in the music you do surrender a sliver of your finite mortal lifespan to. And when the opportunity to learn about something/someone new to you arrives, you’ll be able to leap at it with gusto.

Mosaic Records recently released a 10CD box of recordings from the 1940s by tenor saxophonist Don Byas. I asked them to send me one, because Byas, like Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins, is a player whose name I’ve seen countless times since I started listening to jazz as a teenager, but whose catalog has never really come into focus for me. There are several reasons for this, but a big one is that since a lot of his recordings predate the LP era, and/or consisted of sideman work, only a well-curated compilation will really do him justice, and I’ve never found one.

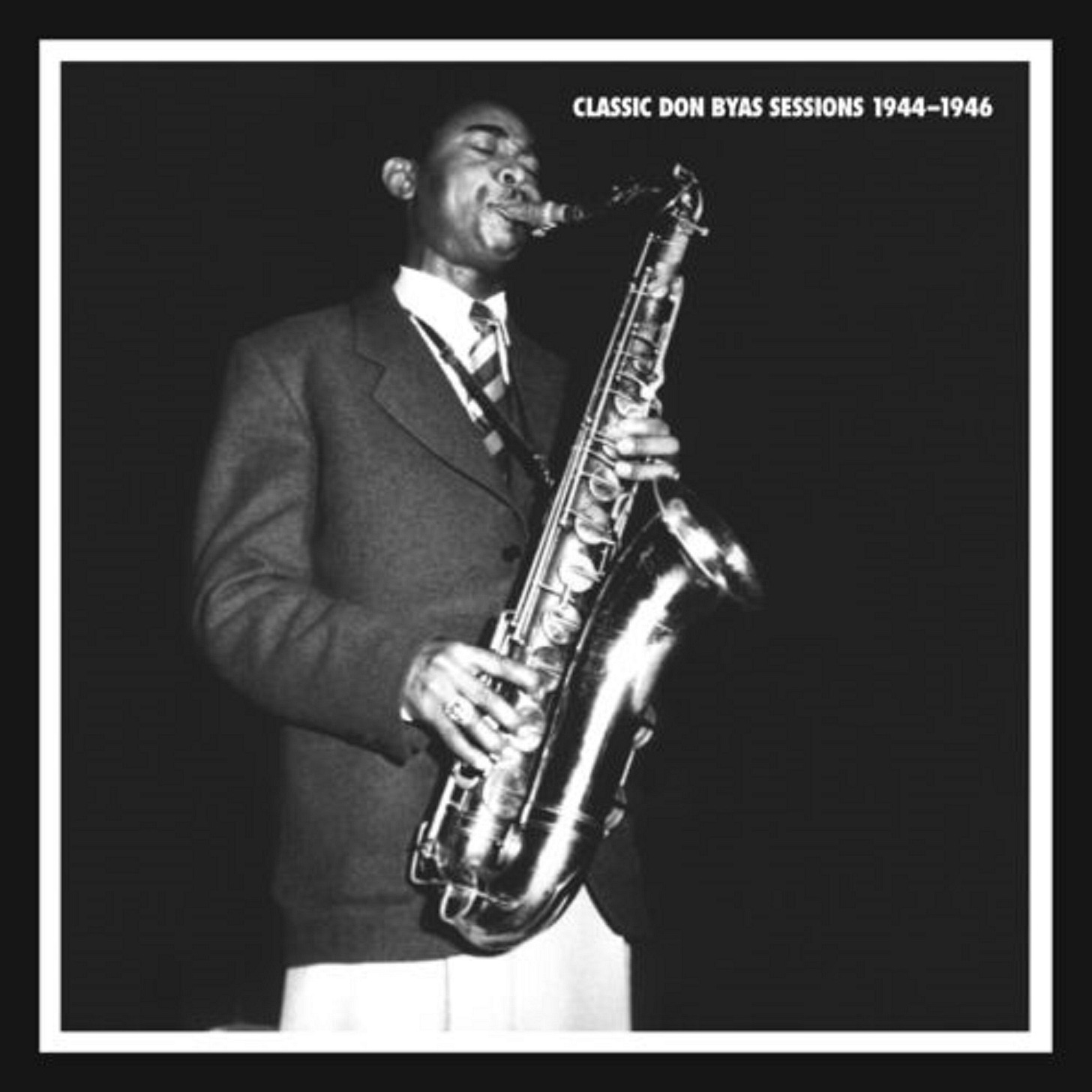

Classic Don Byas Sessions 1944-1946, though, seemed like a good entry point. And indeed, when I sat down last month and listened to it, I learned a lot.

Don Byas was born Carlos Wesley Byas in Muskogee, Oklahoma in October 1913 (sometimes cited incorrectly as 1912). This is strange, because there’s no indication that his parents were Latin. So how did he end up with the name Carlos? In any case, that fact makes his stage name an honorific (as in Don Quixote or Don Francisco), not a nickname. And indeed, he led a band called Don Carlos and His Collegiate Ramblers while attending Langston College (the westernmost HBCU in America) in the early 1930s, and recorded a track in the early 1950s in Paris called “Blues for Don Carlos”.

Byas eventually left Oklahoma for Los Angeles, where he switched from alto sax (and clarinet) to tenor. While there, he played with vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, trumpeter Buck Clayton, and others. By the end of the decade, he was in New York, working with singer Ethel Waters and bandleader Don Redman. In 1941, Count Basie chose him to replace Lester Young in his (Basie’s) band, where he stayed until 1943, when Young returned to the ranks.

Stylistically, Byas can be regarded as a one-man bridge between swing and bebop. A young Sonny Rollins was a dedicated admirer of Byas’s fleet lines and impeccable sense of rhythm; in Aidan Levy’s biography Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins, he quotes Rollins: “Don Byas had the technical proficiency…He was a bebopper who had roots in the earlier school”.

Indeed, listening to Byas, it’s impossible to overlook the old-school aspects of his playing, especially on ballads. When he slows down, he’s got a soft, fuzzy tone, very much in the same spirit as Lester Young, and his approach to melodies is that of a crooner. He seems to be singing, in an earnestly romantic style. When he’s playing a faster piece, though, he toughens up a bit and starts spinning out long lines that point directly to what John Coltrane was doing in the late 1950s, the style that critic Ira Gitler famously called “sheets of sound”. And his feel for the blues is unimpeachable.

(In 1959, Rollins got the chance to play with Byas, backstage in Amsterdam — the younger man’s first time in the city. In Saxophone Colossus, he says, “We went down to my dressing room and we began playing… We played and played and were there for quite a while. Fortunately, I was young and strong, ’cause we almost played up to the time that I should be getting ready for the concert that night.”)

The three years represented on Classic Don Byas Sessions 1944-1946 represent the end of his American career. In September 1946, he flew to Europe for a tour with Don Redman’s big band, and spent the rest of his life there, only returning to the US once, to perform with Dizzy Gillespie’s group at the 1970 Newport Jazz Festival. He died of lung cancer in Amsterdam in 1972, just two months shy of his 60th birthday.

There’s footage of that 1970 Newport performance on YouTube:

In 1962, Byas gave an interview to writer Aris Destombes, for the French magazine Jazz Hot. He said, “When I arrived in Europe with Don Redman’s tour, I immediately felt that I would stay there, and when we were in France, I understood that it would be my second homeland. I like life here, we are free, there is no racial malaise like in the States.”

He spoke about his style, saying, “My friend, all the good tenor saxophones are my students, all of them. I play the most modern of all, modern in the good sense, that is to say while keeping the concern for swing, dance, exchange with those who listen to me.”

What really surprised me, though maybe it shouldn’t have, was that he then swerved into an attack on John Coltrane. “They say ‘Coltrane, Coltrane’ but all that is without real interest…It’s easy for a good musician to play in a complicated, difficult manner. But what’s the point? The processes for quartet and all the systems of harmonic and rhythmic progression developed by Coltrane, that may be valid as pure music, but that’s not jazz as I understand it. And the exchange, what does he do with it? He’s alone, even his partners can’t always follow him... so? And the melody, it’s the same — what would he do with a nice ballad like ‘Laura,’ huh? Talk to me about a tenor like Eddie Davis or one of those good old friends I’ve known for years: the Websters, the Ammons, the Tates, and others: these are jazz musicians. They swing, they make you want to dance and the guys who listen to them understand them. And then the melody, the sound, that’s serious stuff. Coltrane isn’t serious, you understand. He’s a joke compared to good jazzmen who swing and have heart. It’s like with the alto players. Who’s doing better than Cannonball [Adderley] right now? He’s got a huge heart, he’s logical. Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, what are they worth compared to that? Nothing. Jazz must remain an escape from reality and this escape must have a sentimental side; that’s why we create it, not to do style exercises.”

He concluded with an explanation of his philosophical approach to the music, saying, “Yes, Cannonball and others have achieved some good things in that sense, it’s like Fats Waller at the time, but for him, it was to have fun. No, my friend, jazz is the swinging four-beat and the melody that has heart. That is its own, it is its contribution, its essence. This jazz, everyone can understand, everyone can participate in it, we forget reality, our worries and all the rest, we are with jazz, in jazz. And that is how I will always play it.”

Seven years later, still in Paris, he spoke to drummer Art Taylor for what became Taylor’s classic book Notes and Tones: Musician-to-Musician Interviews. He spoke in some detail about his playing style, claiming that he was influenced by pianist Art Tatum. He said, “There’s no way you can hit a wrong note, as long as you know where to go after. You just keep weaving and there’s no way in the world you can get lost. You hit one. If it’s not right, you hit another. If that’s not right you hit another one, so you just keep hitting. Now who’s going to say you’re wrong? You show me anybody who can prove you’re wrong. As long as you keep going you’re all right, but don’t stop, because if you stop you’re in trouble. Don’t ever stop unless you know you’re at a station. [Presumably he means a spot where a phrase resolves in a pleasing way.] If you’re at a station then you stop, take a breath and make it to the next station.”

Taylor also asked Byas, “Do you feel unrewarded for the contribution you made to our music?”

Byas responded, “Yes, in a way, but I can’t say I’m angry, because I split at the top of my success, so actually a lot of it is my fault.”

The Classic Don Byas Sessions box contains 193 tracks, and runs just under 12 hours. In addition to sessions under his own leadership, it includes tracks he cut with trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Hot Lips Page, singer Big Joe Turner, alto saxophonist Earl Bostic, trombonist Trummy Young, bassist Oscar Pettiford, drummer Cozy Cole, and bandleader Benny Carter, among others. These were released on 78s, so they fly by in two and a half to three minutes each.

There are also some recordings never intended for official release, taped in the apartment of Baron Timme Rosenkrantz, a European aristocrat who, like the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter (who supported Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk), was a well-known jazz patron, promoting concerts and recordings and even sponsoring the Don Redman tour mentioned in the previous paragraph. The recordings from Rosenkrantz’s apartment feature Byas and various musicians performing medleys and extended versions of standards. The longest of these is a 12-minute take on “Body and Soul”, but we also get medleys of “My Ideal”, “Sweet Lorraine” and “Sweet and Lovely” and “Stardust”, “Memories of You” and “I Can’t Get Started” as sax-piano duets.

Some of the best sideman recordings are the ones with Dizzy Gillespie’s group, which on this January 1945 date featured trombonist Trummy Young, pianist Clyde Hart, bassist Oscar Pettiford, and drummer Shelly Manne. They run through “Good Bait”, “Salt Peanuts” (here “Salted Peanuts”), and “Be-Bop”, here called “Dizzy Fingers”. The trumpeter’s solos are fast and wild, while Byas is less anarchic but nevertheless proves that he can play as fast as any bebopper.

Indeed, Byas’s unflappable virtuosity often seems to inspire his bandmates to extraordinary heights. On a version of “Should I?” under his own leadership, from just a few weeks after the Gillespie session, he lets trumpeter Joe Thomas state the melody with backing from pianist Johnny Guarnieri, bassist Billy Taylor, and drummer Cozy Cole. But when Byas steps forward, his solo is perfectly dialed-in and passionate at the same time, causing the trumpeter to leap skyward as if he’s been shocked.

Of the tracks released under Byas’s own leadership, I found a series of 1945 quartet sessions with bassist Slam Stewart to be the most compelling. Stewart’s whole thing was to bow the bass while humming/singing the melody one octave higher, and this has the effect of turning him into a co-lead voice, without giving the music a novelty feel. These sessions featured either Erroll Garner or Johnny Guarnieri on piano, but it’s very much a Byas-Stewart duo act with rhythm reinforcement. Several of the titles — “Slam-in’ Around”, “Slam, Don’t Shake”, “Slamboree” — make the relationship clear. Their version of Count Basie’s “One O’Clock Jump” is a particular highlight.

Digging into all this material, I very quickly developed an appreciation for Don Byas’s virtuosic but somewhat conservative style. He came up in the 1930s, when tenor players were supposed to be just one part of a big band, taking the occasional, short solo without disrupting the action on the dance floor. Consequently, he’s at his best when surrounded by a tight ensemble, speeding through a well-rehearsed arrangement like race car drivers, or interjecting a few phrases in between verses by a singer. His musical ideas are concise, not florid; he understood the demands of a 78 RPM recording and said everything he had to say in under three minutes. No wonder he didn’t like a logorrheic player like Coltrane, whom Miles Davis infamously advised, “Try taking the horn out of your mouth”.

So if you’re in search of constant boundary-pushing exploration, and are drawn inexorably to players who are “pushing the music forward”, Don Byas may not be for you. If, on the other hand, you understand the appeal of, in Charlie Parker’s words, “trying to play clean and looking for the pretty notes”, and like a round, burnished dance-band tone, I can wholeheartedly recommend this box set. After several weeks of listening, I would disagree with Sonny Rollins’ assessment, quoted above. Rather than a bebopper with roots in earlier styles, Don Byas was a swing-era player who could hold his own with the beboppers thanks to technical ability, but he was more interested in playing to the crowd than they were. He was right to move to Europe, where he found appreciative listeners until the end of his life.

(Note: They’re beyond the scope of this box, but Byas made some great recordings in Paris in the early 1950s; this early 2000s compilation gathers a pair of sessions that are well worth hearing.)

That’s it for now. See you next week (or on Friday, if you’re a paid subscriber)!

fwiw, my byas go-to had been "complete american small group recordings" (https://www.amazon.com/Complete-American-Small-Group-Recordings/dp/B00006AG9W) and given the price of the mosaic set, it may remain as such!

i agree that byas is a swinger who was advanced enough in his musical understanding to play bop, and i find that moment (let's call it late '30s to the end of the recording ban) fascinating as we hear some older musicians adjust and some incapable of adjusting (and then we get to lester young, who stayed a swing musician all his life but who was incredibly influential on the two charlies, parker and christian). i seem to recall scott devaux's "birth of bebop" exploring this, but admittedly, i read it when it was new, a quarter century ago.

That you for this posting!

Where can I find a pdf of the Jazz Hot article? It sounds so interesting.