Want something for free? I have been offered three one-month gift subscriptions to Nate Chinen’s The Gig, to which I am a paid subscriber. If you’d like to give it a try for a month (Nate’s a smart guy and a good and knowledgeable writer, and I’m not just saying that because he blurbed my book), send me an email and I’ll set you up.

Since moving to northwest Montana, we’ve been gradually making inroads with the local cultural community. There’s an arts center in our town, and a theater that puts on shows in the summer, and there are a bunch of art galleries and individual artists nearby. Sure, some of them might seem a little on the nose, like the guy out on Highway 93 who carves bears out of tree trunks, but there are some abstract painters and sculptors and someone who teaches weaving and fabric arts…there’s a lot going on around here. Honestly, that was a big part of the appeal of the place. It’s a cultural oasis tucked in the middle of overwhelming natural beauty. But I had no idea that a major avant-garde composer was from this part of the world until the album Tête-à-Tête landed in my inbox.

Ruth Anderson was born in Kalispell in 1928, the daughter of a forester with the Montana State Forestry Division. She went to the University of Washington, earning a bachelor’s degree in flute performance in 1949 and a master’s in composition two years later. She then moved to Princeton University, where she was one of the first women admitted to the graduate composition program. She also studied at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. While there, in the 1960s, she developed a keen interest in electronic sound.

Her pieces often featured collaged bits of spoken language, and recognizable songs sliced up and reconfigured, punctuated by electronic noise. In 1968, she established an electronic music studio at Hunter College, which remained open until 1979. It was through that facility that she met fellow composer Annea Lockwood in 1973. In a 2017 interview, Lockwood told me, “Ruth Anderson, my partner, was looking for a substitute teacher at Hunter College, where Ruth had installed and was running an electronic music studio, and Pauline [Oliveros] suggested me. Ruth called me up and invited me over and engineered it and then I was in exactly the place I wanted to be, which was wonderfully nourishing.” The two quickly became a couple, and were together nearly 50 years, until Anderson’s death from lung cancer in November 2019.

(A lot of the information in the two paragraphs above came from my friend Steve Smith’s New York Times obituary for Anderson. He was also the person who commissioned me to interview Lockwood, for the now-defunct Log Journal.)

Anderson never released a full album of her work in her lifetime. Pieces popped up on anthologies, though, and she and Lockwood shared two split releases: a 1981 LP featuring Anderson’s musique concrète works “Dump” and “SUM” and Lockwood’s “Tiger Balm,” and 1998’s Sinopah, a CD with one track from each. Some of her best-known compositions (the meditative drone piece “Points,” the tape collage “I Come Out of Your Sleep,” “SUM,” and a few others) were gathered on the LP Here, which had been in preparation before her death.

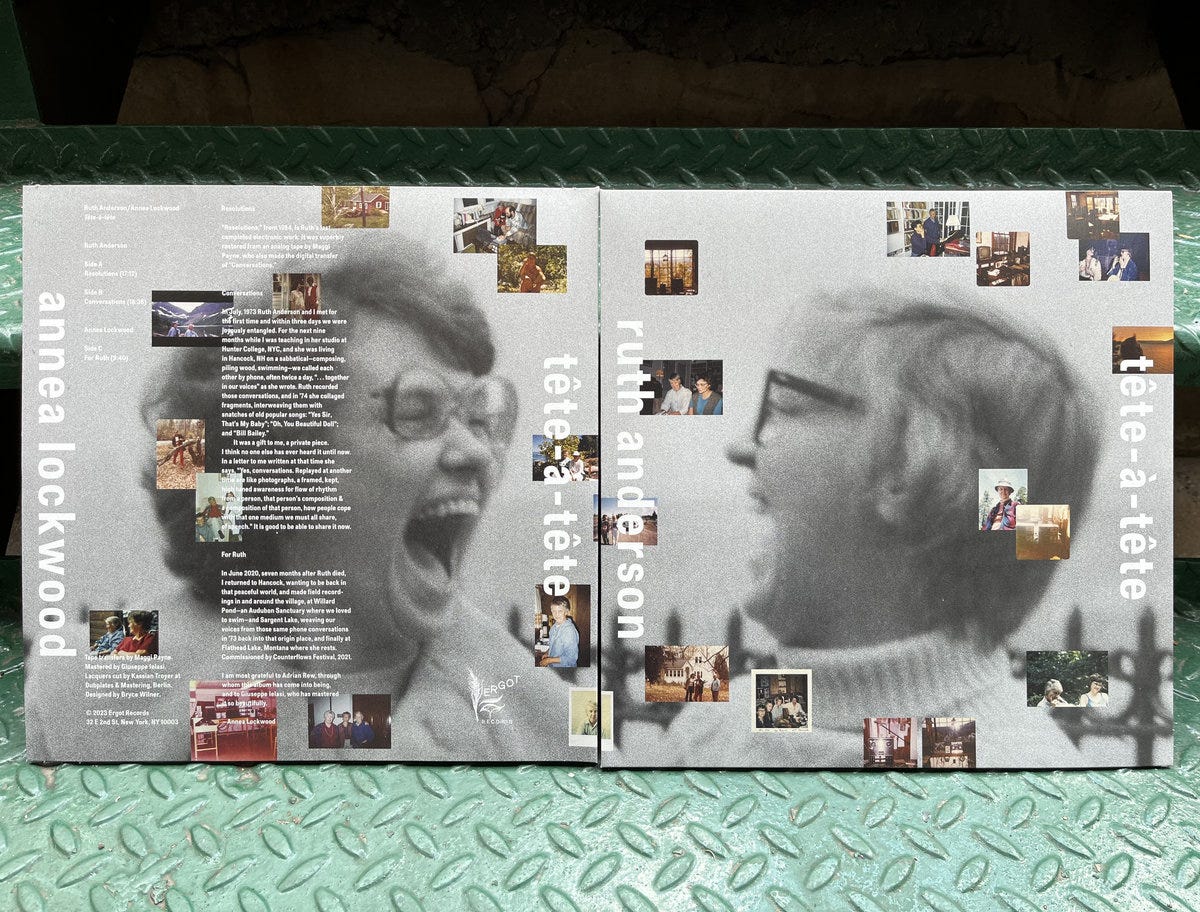

Now Tête-à-Tête has arrived. It includes two previously unreleased pieces by Anderson — “Resolutions” and “Conversations” — and one by Lockwood, “For Ruth.” “Resolutions” is a 17-minute electronic composition from 1984 that charts a slow descent, but it’s not just a steady drone; it wavers and shimmers, like an Éliane Radigue piece played at triple speed. “Conversations” was made in 1974 as a gift for Lockwood; it features recordings of their phone calls together as their relationship was just getting off the ground. A lot of it consists of mutual laughter, which says as much about the bond between them as spoken declarations of love ever could.

Anderson and Lockwood built a house together on Flathead Lake in Montana, and spent decades shuttling back and forth between there and upstate New York. I don’t know exactly where the house is, but I live about five minutes’ drive from Flathead Lake. It’s the largest lake in the western half of the US, and it’s fucking gorgeous. It’s surrounded by tall trees and mountains, and you can stand on the shore and stare out at flat blue water all the way to the horizon. “For Ruth” combines additional recordings of the two women speaking to each other with field recordings of birds, church bells, passing cars, and gently lapping water, taped in Montana and in Hancock, New Hampshire, where Anderson was living in 1974 when their conversations were recorded.

I have to be honest; if I had just heard “Conversations,” I might have described it as almost too personal to be released. It was, after all, initially created as a gift from Anderson to Lockwood. But when shared by its recipient and paired with “For Ruth,” it becomes a gift exchange, a symbol of two lives joined and a conversation lasting decades. And in that context it’s an extraordinarily beautiful work of art.

Burning Ambulance has recently begun partnering with Rihards Endriksons, journalist and artistic director of Latvia’s Skaņu Mežs festival, on the monthly Resonance.fm show Such Music, which is devoted to new works of free improvised music, either previously unheard or created specifically for the show. This month’s episode features an interview with renowned free improvising saxophonist John Butcher and exclusive previews of his three upcoming albums, as well as a glimpse into Marek Pospiezalski’s upcoming Clean Feed release. Listen to the show.

One more thing: Hawkwind’s incredible double live album, Space Ritual, turned 50 last week. If you’ve never heard it, seek it out — it will absolutely melt your brain. Joe Banks, author of an excellent book on Hawkwind, wrote an equally excellent piece for Prog magazine that you can now read online.

That’s it for now. See you next week!