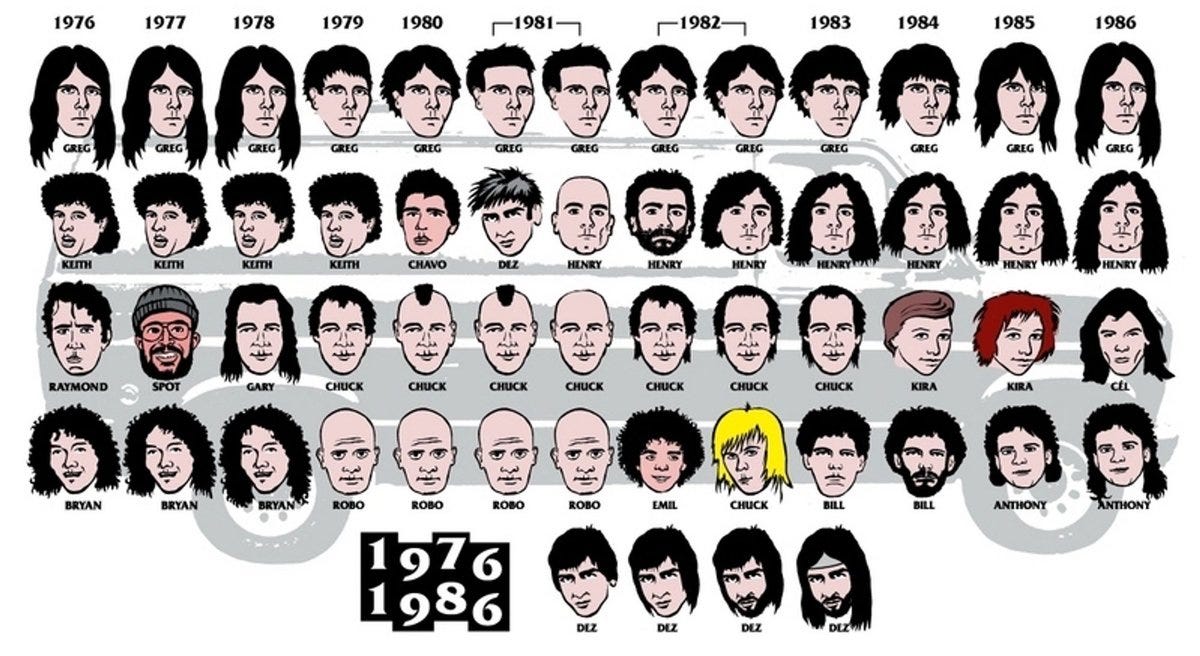

“They were better before Rollins joined.” “They were better before they went metal on My War.” “The five-piece demos from 1982 are the best stuff.” Even close to 40 years after their breakup, there are plenty of opinions about Black Flag floating around, most of which are bad and dumb. In this week’s newsletter, I am going to share with you the truth about Black Flag, which is that they, like most great bands, got better as they went along, and their final studio albums were not only their best work, but some of the best rock music of the ’80s, “underground” or otherwise.

Black Flag were prevented from recording or releasing music for three years, after legal issues related to the release of their 1981 album Damaged. And much the way the World War II-era recording ban kept the development of bebop hidden from most jazz fans, so that the style seemed to emerge fully formed in 1945, when Black Flag returned to record stores in 1984, they exploded out of the gate. They released three full-length albums — My War, Family Man, and Slip It In — in 1984, plus the Live ’84 cassette. All of these records, and the relentless touring the band did, playing nearly 180 shows in 1984 alone, revealed that the group had virtually abandoned the fast, minimalist hardcore punk that had won them their early audience, and were now an unclassifiable amalgam of punk, metal, and a particularly gnarly take on jazz-rock fusion. And the following year, they journeyed even farther out.

Loose Nut, recorded in March 1985 and released two months later, was the logical next step. The songs were tighter than those on Slip It In, with less space given over to extended soloing by Greg Ginn, but retained the metallic energy. “Bastard in Love” and “Annihilate This Week” were built around riffs as big and catchy as anything coming from Ratt or Dio, while “Best One Yet” and “This is Good” explored the abstract, almost jazzy art-rock side of their music. (The latter track seems particularly influenced, from its title on down, by Swans, though it’s much faster than anything Michael Gira and company were doing at the time.)

Black Flag had stopped working with engineer Spot after their 1984 run; Loose Nut was recorded by Ginn and drummer Bill Stevenson, with engineer David Tarling. And though they were using the same studio — Total Access in Redondo Beach — the sound was much fuller, punching its way out of the speakers. The drums are fantastic, with a dry-but-pummeling sound similar to the one Rick Rubin would get on the first Danzig album.

The songwriting was also slightly more democratically divided. For much of their career, Greg Ginn had written both the music and the lyrics. But Rollins began writing lyrics on My War, and by Loose Nut there were multiple songs that Ginn had no hand in at all. “I’m the One” and “Best One Yet” were co-written by Rollins and bassist Kira Roessler; “Modern Man” was a cover of a song by Würm, a band co-led by Black Flag’s previous bassist, Chuck Dukowski; and “Now She’s Black” was by Stevenson.

The band spent much of 1985 on tour. As Roessler said in a 2021 interview,

“We were either practicing to make a record, or we were on tour or recording. If you ain’t playin’, you’re payin’! The approach with them was very rigorous. I thought that Black Flag was an anomaly in terms of their work ethic level.

“There were no other bands touring as extensively. There were bands touring, of course, but that network of college radios, promoters that Black Flag was establishing before I joined the band and continued after, actually shaped touring for many of the other bands afterwards.

“We didn’t meet a lot of other bands with the same schedules — practicing five hours a day, two hours a show. Seven records in two years! We were attacking it with a vengeance that was unusual.”

In September 1985, the band released The Process of Weeding Out, a four-track instrumental EP recorded at the same March session that had produced Loose Nut. It consisted of two nearly 10-minute tracks and two shorter ones, and the music was astonishingly powerful. These weren’t just Black Flag songs without words. Ginn, Roessler and Stevenson had been playing instrumental gigs off and on since the beginning of the year, and even opening some regular shows that way. (A protean version of “The Process of Weeding Out” kicks off Live ’84, and it’s absolutely crushing.) They had their own language by this point, and were capable of improvisational flights that bridged the gap between fusion and thrash metal. The EP is both a line in the sand and a torch held aloft.

The final Black Flag album, In My Head, was recorded in May 1985, and was originally intended to be a) entirely instrumental and b) a Greg Ginn solo record. “But Henry had been hanging out and listening to the music, and he really dug it,” Roessler recalled in Stevie Chick’s Spray Paint the Walls: The Story of Black Flag. “I don’t know if he felt left out or something, or if he felt inspired or whatever, but he stepped up and wrote lyrics for some of the songs.” Rollins ultimately contributed lyrics to five of the 12 songs on the CD and cassette versions of the album (“Paralyzed”, “White Hot”, “In My Head”, “Drinking and Driving” and “You Let Me Down”), and Roessler and Stevenson brought in “Out of This World.”

The songs on In My Head often feel like they were written as instrumentals. They have simple, repetitive melodies (not riffs) and there are multiple layers of guitar — on “Black Love”, for example, there are three or even four Greg Ginns harmonizing with or soloing over each other, as Roessler and Stevenson maintain a plodding, thudding groove. That’s another thing about these songs; they’re slow and heavy in a doom-metal way, less hooky than the ones on Loose Nut. And Rollins’ vocals are heavily treated, subjected to reverb and floating separate from the music in the mix. He’s frequently drowned out by the guitars, which was never the case in the past.

This is some of the most alienated-sounding rock music ever recorded. You read stories about how bands like Pink Floyd made some of their best-known work without even being on speaking terms with each other, and it seems insane. But when you listen to In My Head, that same dynamic — four musicians completely walled off from each other — is inescapable. And indeed, not long after the sessions, Ginn would fire Stevenson, replacing him with a new face, Anthony Martinez, for the summer 1985 tour.

All the alienation and recriminations boil over on the title track, though, and the result is one of the best songs in the whole latter-day Black Flag catalog. Over a foundation riff as heavy as anything from their frequent tourmates Saint Vitus and a pounding beat from Stevenson, Rollins delivers paranoid, hallucinatory, doomed verses about hearing voices and wishing destruction on a lover. Ginn’s solo is more conventionally beautiful than almost any other track on the album (compare it to the genuinely unsettling sounds he uncoils on, say, “I Can See You”); it still saws discordantly at your nerves, but you can also throw the horns to it if you want. “Drinking and Driving” is a return to the satirical party-metal of “Annihilate This Week”, so it’s no surprise that was the “single”; they even made a video for it.

(Click through to YouTube to read the director’s memories of making that video.)

While touring in support of Loose Nut, the band — Ginn, Rollins, Roessler and Martinez — recorded an August 1985 performance in Portland, Oregon which became Who’s Got the 10 1/2?, released in March 1986. In keeping with their drive to constantly move forward, the set list included eight of the nine songs from Loose Nut, as well as “In My Head”. Rollins has been known to call Who’s Got the 10 1/2? his favorite Black Flag album, and it really is an astonishing document. They’re harder and heavier than on Live ’84, and a lot of the credit goes to Martinez, who wasn’t a great drummer when the tour started, according to Roessler, but who at this point was absolutely locked in with her. Rollins is in strong form, and Ginn and Roessler are both playing with real ferocity, but also stretching out at times — they turn “Slip It In” and “Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie” into a nearly 15-minute jam, and there’s an untitled instrumental (simply called “Jam”) that’s more of the barbed-wire jazz-rock heard on The Process of Weeding Out, like if John McLaughlin joined the Stooges.

By the end of the tour, though, things were getting ugly. Roessler was leaving to finish college, and Rollins was delivering bilious onstage monologues aimed in her direction. (He apologized some in the afterword to the 2004 reprint of his book Get In The Van.) The final Black Flag tour, with Ginn, Rollins, C’el Revuelta on bass and Martinez on drums, was by all accounts a hard slog, and no official live recordings have ever been released. The band played its final show in Detroit on June 27, 1986, and as Rollins wrote:

At some point in August 1986, I was in Washington DC when Greg called me. He told me that he was quitting the band. I thought that was strange considering it was his band and all. So in one short phone call, it was all over.

In a way, it was a relief. I don’t think any more good music would have come from the band, seeing how we didn’t get along anymore. Looking back at it, it was a good time to stop. It was time to do something else.

Professionally and artistically, Black Flag went out on top. They were selling out decent-sized clubs nationwide and the band was well known even outside the confines of the punk scene; In My Head and The Process of Weeding Out were the subject of a very positive critical essay by the critic Robert Palmer, in the New York Times. He concluded, “The jazz great Charlie Parker insisted that there are only two kinds of music anyway, good and bad. Black Flag’s In My Head and The Process of Weeding Out are good music.”

For some reason, though, the critical tide has turned in the years since the band’s breakup, and they are now more often praised for their DIY ethic and the intensity of their live shows (and the nationwide underground network of performance spaces they helped build through relentless touring) than for their actual music. Which is why it’s time to go back to Loose Nut, The Process of Weeding Out, In My Head, and Who’s Got the 10 1/2? and recognize that Black Flag were in fact one of the best, most consistently challenging (to themselves and their audience) bands America has ever produced.

One more thing: My latest Stereogum column ran last week. I wrote a long essay about Tyshawn Sorey’s recent collaboration with pianist Aaron Diehl, and reviewed albums by JD Allen, Isaiah Collier & the Chosen Few, Ezra Collective, Darius Jones, Charlie Parker, Aaron Parks, Masahiko Satoh and Takeo Moriyama, Daniel Sommer/Arve Henriksen/Johannes Lundberg, Anna Webber, and Immanuel Wilkins.

That’s it for now. See you on Friday, when I will ask you for money.

Honestly I could never quite tell if it was boldness or inattentiveness, but most bands would be embarrassed to release a live record as DRY as ...10 1/2. Not because there's anything inherently wrong with that sound, but because there's nothing to hide the slop and the mistakes. But they had nothing to hide here.

I can take or leave every other Flag record but for my money it's probably the best live album of all time, by any artist in any genre.

Process & Who's Got...were my first intro to Black Flag at 13. Those albums will always be my favourite version of Black Flag, even though I'd move backwards to the earlier stuff, and love that in a different way. But that unhinged heaviness of late Black Flag is way more in line with what I love of about mid 80s American underground–damaged, off-kilter, free to be on edge and dangerously weird.